Straddling the Sierra Nevada mountain range, the alpine region of Lake Tahoe remains unparalleled in its crystalline lake water and panoramic mountain views. With such natural treasures, one has to wonder what place a water slide, rollercoaster, or artificial lazy river could offer. Developments such as these however are threats currently facing the region.

Since 2011, Alterra Mountain Company, owner of Olympic Valley’s ski resort Palisades Tahoe, has aimed to make such plans a reality: the 247,000-square-foot development would include a recreation center of unprecedented scope, including water slides, indoor sky-diving, and artificial rivers. Environmental concerns such as improper water use and wildfire danger have been of the utmost concern to local Truckee-Tahoe nonprofits Sierra Watch and Mountain Area Preservation.

Placer County first approved plans for the development in 2016, a decision that Sierra Watch took to court; the county’s 3rd District Court of Appeals voted in favor of the nonprofit and ultimately rejected the plan. But the decade-long battle for Olympic Valley’s future continues.

“It’s been a 10-year fight to stop this development, a great victory — and that’s the good news!” recounts Sierra Watch’s Executive Director, Tom Mooers. “The bad news is, Alterra applied for a new round of entitlements from the same failed plan, and that’s what they’re pushing through now.”

The court deemed Alterra’s initial environmental assessment inadequate, however, no changes to the original plan have been made, the most recent submission simply offering defenses of its original points. “To say pollutants from the added emissions would not impact the area, for example, is bogus, because there is decades worth of science to back that up,” says Mountain Area Preservation Executive Director Alexis Ollar, adding the project would be an “invasive amount of development” for the region.

Sierra Watch and MAP are far from alone in their concerns. Behind Tahoe Truckee True, the campaign launched in response to Alterra’s proposal, is an impressive 10-thousand-person grassroots army dedicated to the cause. Following the project’s revised environmental impact report in November of 2022, Sierra Watch submitted detailed comments to Alterra, along with many local individuals. “We engaged experts in hydrology, traffic, and public safety…but maybe even more importantly, thousands of citizens wrote their own comments to say what concerns they had about the development,” Moers says.

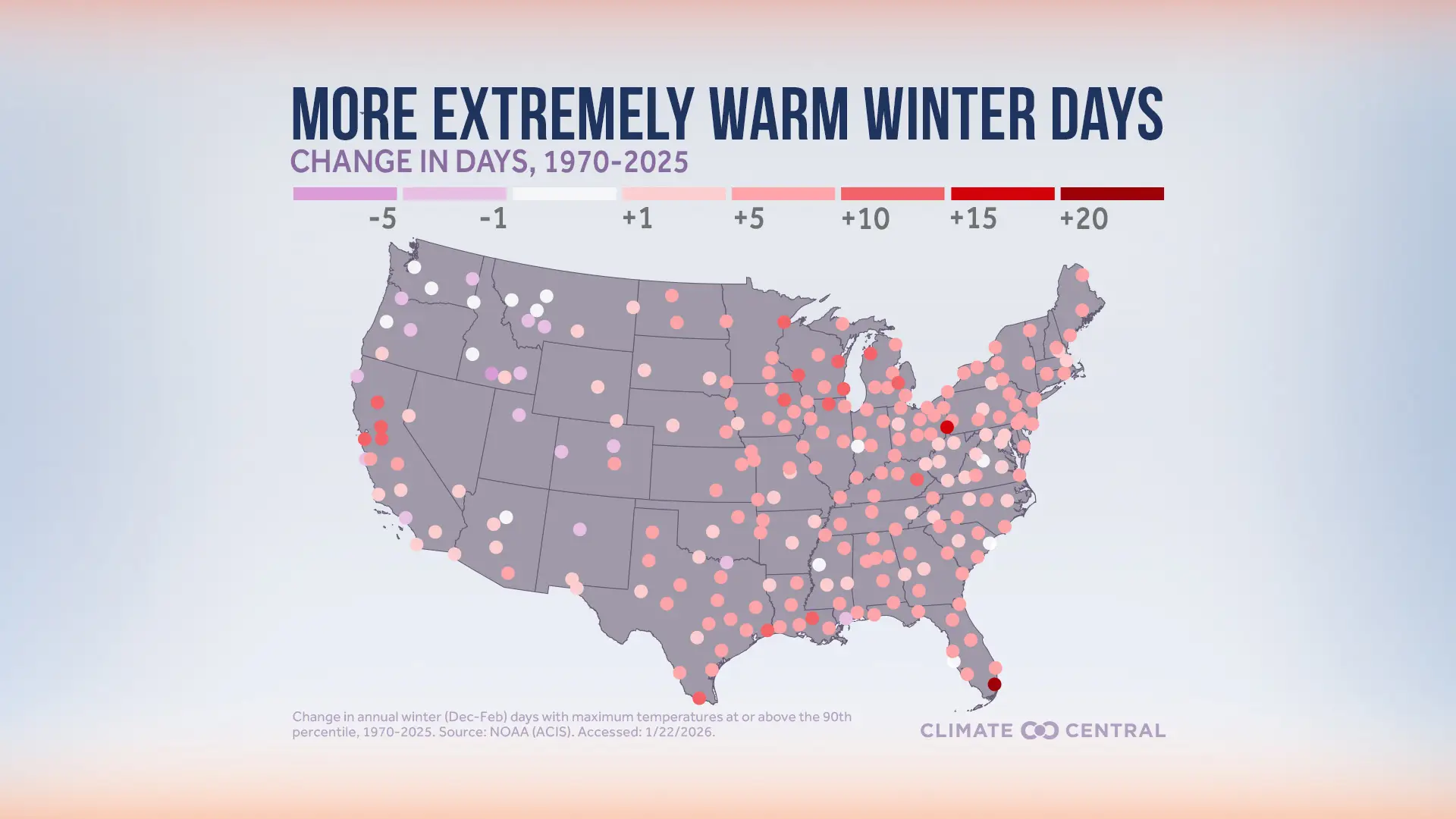

Since the project’s initial proposal in 2011, environmental worries such as fire hazards and strained water supplies have only been exacerbated by the warming climate.

Despite the region’s recent snowy winter, California and Nevada still linger in drought, and the piping of water for a non-essential development such as Alterra’s brings up questions about resource responsibility. MAP’s advocacy director, Sophia Heidrich, says the water for the indoor water park or lazy river would be taken from Olympic Valley’s aquifer, a supply under increasing strain.

“The idea that we would literally suck water from the streams in order to build a fake, lazy river is insulting,” adds Mooers. “There is a long, multi-generational commitment to protect Tahoe, and to respect the mountains, and the idea of an indoor water park is a threat to that multi-generational legacy.”

Wildfires — another natural phenomenon intensified by climate change — threaten vast areas of wilderness like the Lake Tahoe Basin, its largest fire in recent history being that of the Caldor fire, having burned 221,835 acres in 2021.

Mooers says the consequences of this development could be deadly in the event of a fire, as it would add 3,000 new daily car trips to the current traffic. “Under [Alterra’s] own analysis, it would take more than 11 hours to escape a fire in Olympic Valley…If people can’t get in on a winter day, what makes us think people will be able to get out if there’s a fire?”

Both nonprofits say they are not anti-development but rather aim to work alongside developers to realistically accommodate both parties. “Working with [Alterra] could solve so many issues, they just don’t listen when we say this project won’t work for us,” Heidrich says.

As of March 2023, the comments submitted to the proposal by Sierra Watch and the many concerned locals impede the project’s progress. According to the Placer County Planning Services Division, staff are currently reviewing the comments, “and will provide written responses to all comments in the Final EIR, which will be prepared over the next several months.”

“I don’t think it’s gonna be that easy for them,” says Mooers. “I think they’re learning we’re not going away.”

Hannah Truby is a graduate student in the Media Innovation program at the Reynolds School of Journalism. She is a student in the News Studio: Science Reporting class.