We humans have a habit of touching our faces 68 times per hour without being aware of it. Mindfully tallying our touches can reduce the risk of catching the novel coronavirus.

“I can’t help but notice that you haven’t touched your face during this telemedicine call,” my doctor said, adjusting her surgeon’s face mask and sweeping back a few stray hairs behind her ear. She scratched her ear lobe and adjusted her mask again. “How is that possible? I can’t seem to stop touching my face!” she remarked, a note of mild irritation in her voice.

“Oh, I’m surprised you noticed,” I began. “Actually, I just learned how to do that last week. It took less than an hour to start to train myself to not touch my face.”

As U.S. government officials struggle to control the spread of the novel coronavirus and haphazard state reopenings have led to record new infections, Americans are increasingly on their own when it comes to avoiding becoming infected with SARS CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

One strategy that may reduce infection is to avoid touching your face – but that’s hard to do, as it is hard-wired into human behavior.

“Rubbing eyes, scratching nose, curling fingers against mouth or chin, chin resting on a hand (‘Rodin’s thinker’) are all distinctive … of face-touching in primates,” according to the Annals of Global Health. Health experts worry, however, about whether these natural inclinations put us at risk for self-infection.

A typical person touches the T-zone (the area of the eyes, nose and mouth) on his or her face 68 times per hour, on average.

During a pandemic, when touching a fomite (any surface potentially contaminated with the virus) such as a door knob, light switch or gas pump puts you at risk of contracting disease, so finding a way to avoid face-touching can mean the difference between being healthy or hospital-bound.

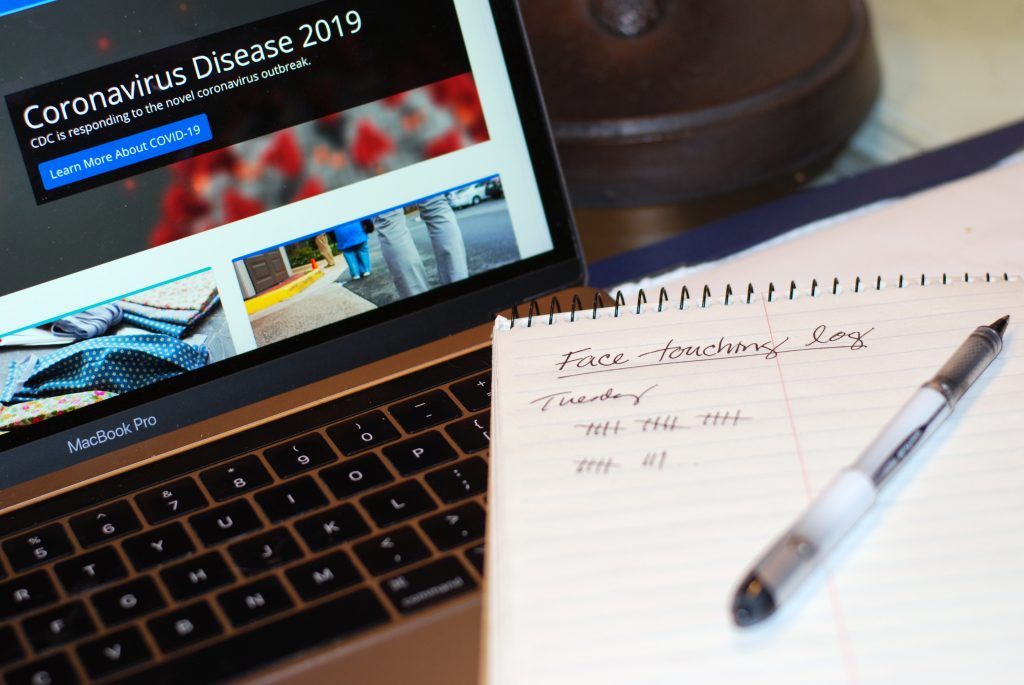

The behavior modification technique I learned about, called self-monitoring – or counting how many times you do something – has been known to science for more than 50 years. I first ran across it in a blog post written by Stephen C. Hayes, Ph.D., a foundation professor of psychology at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Professor Hayes’ secret? Leverage the well-established power of self-monitoring to reduce your frequency of negative behaviors, whether those behaviors are touching your face, reaching for that extra donut, or pouring a superfluous glass of Sangria.

“We picked face-touching because it was high-frequency; you can measure it without people knowing you’re doing it; you can measure it from far away; and it’s reactive.” Hayes said. “Face-touching is negative enough, it’s correlated with self-focus, so it’s negative for not only the individual, but for those watching it.”

Writing in Nevada Today (2020), Hayes lays out how it works:

“Keep a running tally of every single time you touch your face. It may take a short time to sink in, but it’s important to become conscious of it. Leave your assessment sheet in easy view. Very soon that simple act of recording your face touches will reduce it to near zero, and just seeing the recording sheet will help remind you of it.”

Face-touching: much ado about nothing?

Though not the primary means of infection, fomite (surface)-to-face transmission is a plausible (though, according to the CDC, not likely*) source of spread of the SARS CoV-2 virus.

This virus is mainly spread by inhaling a sufficient viral load of airborne respiratory droplets from an unmasked, infected person. Viral transmission is almost immediate among unmasked infected people who cough or sneeze in the direction of unmasked uninfected people. Though it can take up to 50 minutes for infection to occur when an unmasked, infected person is talking in normal tones to an unmasked, uninfected person within a six-foot distance.

In addition, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients can and do spread the virus to surfaces. According to Nature (July 2020), hospital patients who are infected with the virus spread it widely on nearby surfaces as well as into the air, putting those around them at risk.

In day-to-day life in non-hospital settings, though, surface-to-face transmission of the virus “is extremely rare,” says Dr. Trudy Larson, dean of the School of Community Health Sciences at the University of Nevada, Reno. Larson, who serves on Nevada Governor Sisolak’s Medical Advisory Team for COVID-19.

“It’s a possibility that, if you touched a surface shortly after somebody coughed or sneezed all over it and you put your hands there and then rubbed your nose or your mouth. Clearly, the information we have now does not support a major role of face-touching in transmission,” Larson said.

How does self-monitoring work?

Investigations into self-monitoring go back to the late 1960s, when a number of behavioral psychologists – Frederick H. Kanfer, Alan E. Kazdin and Howard Rachlin, Rosemery O. Nelson and Steven C. Hayes among others – began looking at self-monitoring as a therapeutic strategy to help patients reduce the frequency of negative behaviors.

“What seems to be happening,” Hayes said, “is that it (self-monitoring) is bringing to mind, bringing your conscious attention (to the unwanted behavior). It’s functioning as a cue for the relationship between actions and consequences. You’re noticing. Let’s say you’re self-monitoring calories. If you’re trying to lose weight, you restrict your calories. If you’re trying to gain weight, you increase your calories. It’s a cue reactivity phenomenon linked to your contact with actions and consequences.”

Self-monitoring seems to be effective across cultures and time, too. “It’s pretty much a universal principal,” Hayes said. “One reason is that you’ve got a prominent instrument (such as a pen and paper or a phone for recording) or a device that you can carry with you and prominent enough that you notice it’s there and the cue-reactivity comes from the action of self-monitoring but eventually goes into the device itself.

[For example,] if you’re using an iPhone for self-monitoring, just placing it in front of you changes the behavior in the direction you want it to go,” Hayes said. Other common self-monitorin methods include pad and pencil, hand tally counters (“clickers”) or a simple calculator.

Experts agree that self-monitoring works

Self-monitoring has a long history of therapeutic use in the behavioral sciences, says psychiatrist Melissa Piasecki, M.D., executive vice president and associate dean of the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine. “It’s most commonly used in the treatment of people with obsessive behaviors, such as trichotillomania, or hair-pulling. With trichotillomania, you have the patient collect the hair, put it in an envelope, count it, chart it … you make it kind of a big deal that you’re tracking the data. For some folks, just tracking it seems to be enough to manage or stop the behavior.” Piasecki said.

“In smoking research, a group of graduate researchers would monitor smokers’ carbon monoxide levels,” Piasecki said. “When the subjects came in, they’d say, ‘you know, the thing that made the biggest difference this week is that I knew you would be measuring my carbon monoxide.’ That’s not self-monitoring, but it’s the impact of assessment. Similarly, asking people to track their drinking behavior can lead to decreased drinking,” Piasecki said.

The quantified self: self-monitoring through the ages

Throughout history, men and women have sought to improve their wellbeing by tracking and modifying their behaviors. As a young man, Benjamin Franklin sought to reach moral perfection by writing out the names of 13 “virtues” and keeping a written matrix to track his efforts to master them.

During the Victorian era, English novelist Anthony Trollope set out to write for three hours every morning. He, too, kept a diary. It worked, he wrote, because, “There has been the record before me, and a week passed with an insufficient number of pages has been a blister to my eye, and a month so disgraced would have been a sorrow to my heart.” Trollope went on to publish 47 novels, 17 nonfiction books and two plays.

Coinciding with the early self-monitoring work of Kanfer, Kazdin, Rachlin, Nelson Hayes and others, the early 1970s saw the birth of quantimetric self-tracking movement, which reached its zenith in the early 2000s when the FitBit and other wearable fitness tracking devices came to market.

Criticism of quantimetric self-tracking and later, the “quantified self” movement, included the anxiety brought about by constant self-monitoring as well as the everyday wearers’ inadequacies in analyzing and interpreting the massive amount of data they harvested from their wearable devices.

Nevertheless, adding a self-monitoring regimen to your day is just another arrow in your quiver to help avoid infection, whether from the novel coronavirus, colds or influenza. As Larson noted, “It’s all about not touching your face … the self-monitoring technique is amazing for all respiratory viruses.”