Despite all the favorable conditions and high demand for solar power in Nevada, there are challenges.

There’s the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely to stall or even cancel some solar projects that are under development, according to federal energy projections. There’s a more fundamental problem as well, though: the sun doesn’t always shine. That’s why more battery storage is needed to capture and store solar when the sun is up, so utilities have enough to deliver when the sun is down.

But one Nevada solar plant — the Stillwater plant outside Fallon — has found another solution.

Solar farms aren’t usually loud, but Stillwater is not usual. That’s because it’s not just a solar facility. Yes, there are plenty of solar photovoltaic panels — 285,007, to be exact — but they’re mostly quiet. The cacophony comes from a big pump called a heat exchanger, part of the plant’s geothermal facility.

Stillwater draws energy from both the sun and the earth. Head over to the control room and you can see how the two complement each other.

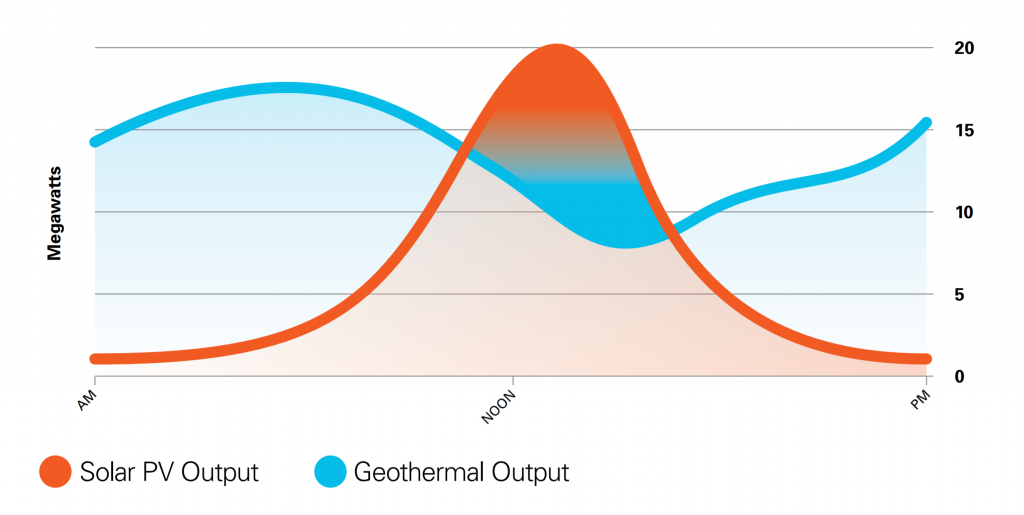

“So this is nighttime to daytime, and you can see here how exactly the solar fills in the trough of the geothermal,” said Chuck Salo, pointing at two graphs on one of the many computer monitors in the room. Salo oversees solar and geothermal technologies in the western U.S. for Enel Green Power, the Italy-based company which owns Stillwater.

The first graph gives the plant’s solar output over the past several hours, the other its geothermal output. They look like mirror opposites of each other.

“The solar is coming online with the sun and its power curve is beginning to come up with the sun and it maximizes throughout the day while the geothermal net output is at its lowest,” Salo said. “And then the inverse happens as the sun goes down at night.”

Solar and geothermal are tag-teaming. Solar panels generate their most power when the sun is up —obviously. Less obvious is that the geothermal technology at Stillwater generates its most power at night, because there’s a big difference between the temperature of the earth’s hot surface and the temperature of the cold nighttime air.

“As our solar is decreasing, our geothermal is increasing,” said Salo. And vice versa.

All of this means that the plant can feed power onto the electric grid literally day and night. But again, Stillwater is unusual. Enel Green Power says that these hybrid plants are rare because they require more land, more transmission infrastructure and more capital investment than a single-technology plant. In fact, Stillwater is the only hybrid solar-geothermal plant that serves NV Energy customers.

Whereas Stillwater can run 24/7, other solar plants can’t.

“Unless there is some effective storage, we will quickly become capped out at how much solar power we can produce and use,” said research professor Kent Hoekman, who studies renewable energy at the Desert Research Institute in Reno. He said that many solar plants overproduce power during the daytime hours, when demand is relatively low.

“They produce more electricity from solar than they can use,” Hoekman said. “There’s not that much demand for the electricity. They have to throw it away!”

Then, when demand peaks in the evening, there’s no solar and the grid has to turn to dirtier forms of energy like coal and natural gas. That’s a problem for a state trying to cut down on its carbon emissions.

Just last year, Nevada upped its Renewable Portfolio Standard, a state mandate that dictates how much energy sold by electric providers must come from renewable sources. The latest version, passed by the legislature and signed by Gov. Steve Sisolak, calls for 50% by 2030.

Hoekman said it will be extremely difficult to meet that goal in just ten years’ time, although it is within the realm of possibility. But if the state is going to hit that 50% target — be it ten years from now or later — batteries will be indispensable.

“Development of battery storage is happening quickly, and I can foresee some years from now when it will be cost-effective to store significant amounts of solar-generated electricity in batteries for use at times at night,” Hoekman said.

He isn’t the only one foreseeing more cost-effective batteries. So is the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, which projects that capital costs for battery storage will be 20-70% cheaper in a decade, compared to how much they cost in 2018.

These favorable cost projections are emboldening some energy companies to double down on battery storage like never before. When renewable energy consultant Rebecca Wagner served from 2006 to 2015 on the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada — which reviews proposals from energy companies looking to set up shop in the state — there were no proposals for solar plants with battery storage. But things have since changed.

“Most of the new projects that have been approved for Nevada have — at least the last round — have significant battery storage,” said Wagner, referring to a handful of NV Energy solar plants currently under development with battery storage in the works. The utility is planning for three of them in northern Nevada.

COVID-19 is expected to delay some solar projects across the nation. As for Nevada in particular, a spokeswoman for NV Energy said in an email to KUNR, “All of our renewable projects are an important part of our future renewable portfolio and we look forward to these projects’ successful on-time completions.”

To be sure, the pandemic has dealt a blow to the energy sector. It’s disrupted global supply chains, which energy companies rely on to source materials for their solar panels and batteries. Consequently, energy analytics firm Wood Mackenzie lowered its 2020 forecast for solar storage installations by 20%. But the firm also expects the storage industry to bounce back to its pre-coronavirus level of business as early as next year.

So, even though the present moment may be bleak, the long-term outlook for solar storage remains rosy. That’s thanks to technological gains made in recent years.

“Lithium-ion batteries in general have had a ton of development with the advent of their use in portable electronic devices,” said Dan Simpson, a Tempe-based electrical engineer who works for engineering consultant firm IMEG.

“They keep getting better at making them,” said Simpson, who has worked on utility-scale solar projects, including for Arizona Public Service, the state’s largest electric utility. “The same kind of batteries that are commonly being used in battery energy storage systems are also used in laptops, phones, et cetera.”

So breakthroughs made in small batteries — like the one in your phone or laptop — can carry over to big batteries, like the ones used at solar plants. That makes them more cost-effective.

Of course, as with any investment, there are risks involved. Plans can backfire, literally. Simpson says utility-scale batteries have caught fire. And then there’s the risk of the battery becoming obsolete.

“Technology in general is evolving so fast that anytime you make a large investment in any sort of technology, there’s a risk that next week some new whizzbang technology could come along that’s just so much better than what you just spent all that money investing in,” Simpson said. “And lithium-ion batteries are no exception. But my guess is it’s a relatively minor risk that the odds of a major breakthrough that then gets brought to market occurring over the five- to seven-year life span of your battery is probably a pretty negligible risk.”

Back at the Stillwater plant, Enel Green Power regulatory affairs officer Terry Page said that batteries were way too expensive when Stillwater was built in 2009.

“When this design was proposed — that is, the offsetting solar against the geothermal — you couldn’t buy batteries to do what we did for the price of what we did here,” Page said. “Now the batteries are less. Every project we’re going to do in the future, we’re looking at whether or not a battery will work.”

And that is something many other power companies will be looking at throughout this new decade.

This story also aired on KUNR Public Radio.