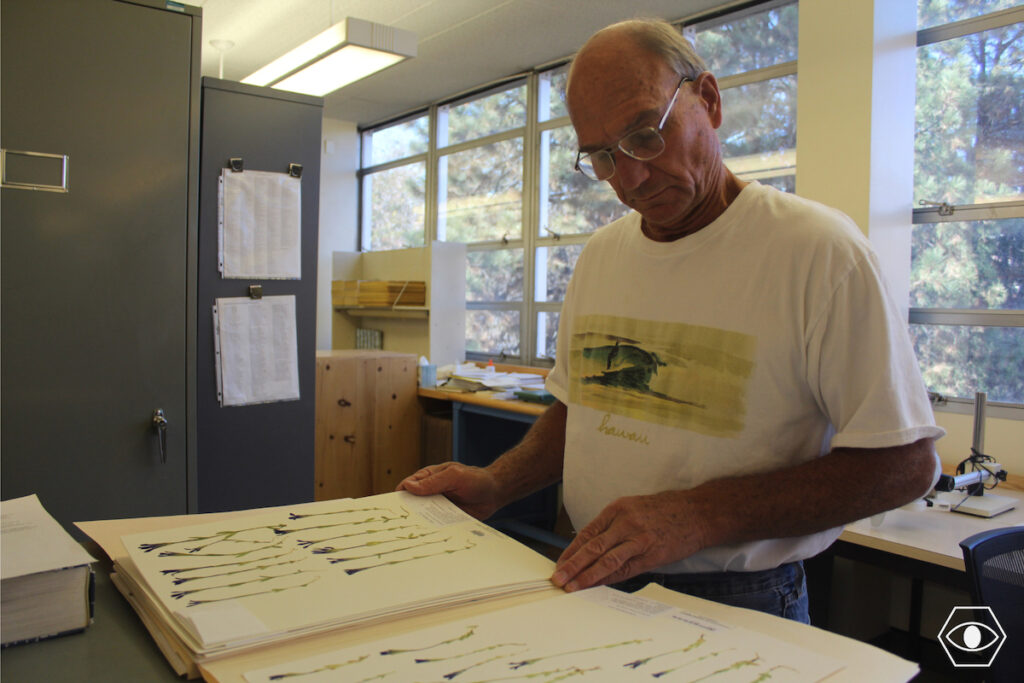

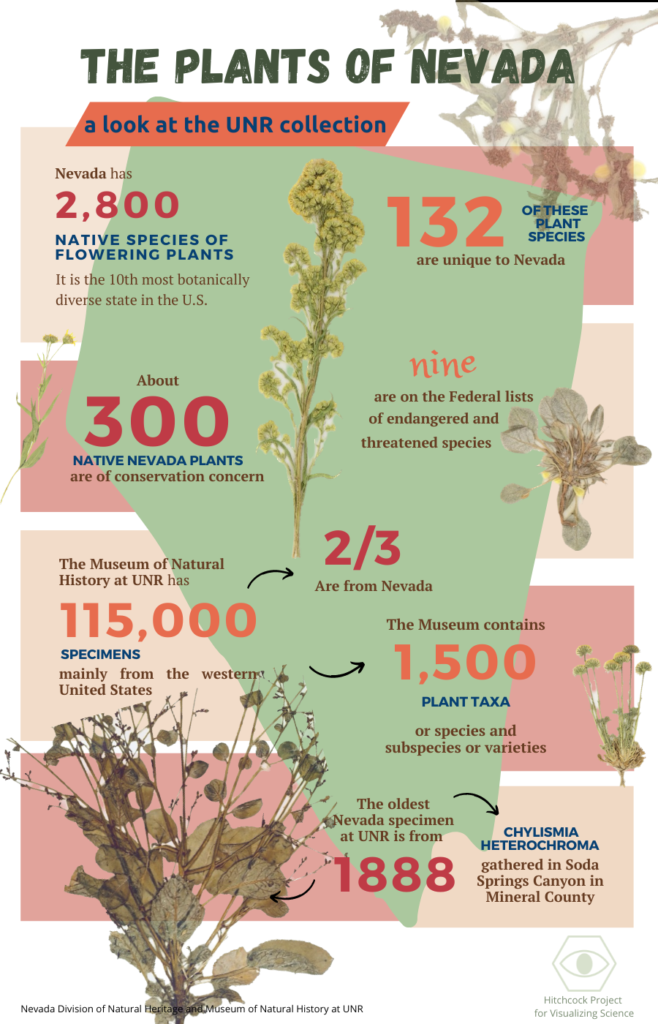

Before the inclement winter weather freezes them, during the warm days of spring or early summer, or the cool evenings of early fall, Arnold “Jerry” Tiehm, 70, digs up plants and quickly presses them in past-read newspaper sheets, so they do not wilt. Equipped with his hiking boots, eyeglasses, notebook, hammer, plant press, and pen to take notes on the places and plants, he has been collecting and pressing plants for over 49 years. He has helped create a collection of more than 115,000 specimens at the University of Nevada, Reno, over two-thirds of which are from Nevada.

Now, as the curator of herbarium for the Museum of Natural History at UNR, Tiehm is using all of his past knowledge and field work to help collect and document every plant species in Nevada, linking each record to a physical specimen, the place where it was found, and every Nevada county in which that plant occurs.

In doing so, Tiehm not only is demonstrating the diversity of plants and habitats in Nevada – even finding new plant species – but he is also helping create the first comprehensive and corrected list of plant species in the state.

“I grew up in Nevada, a place that botanically has always sort of been the last frontier in North America,” Tiehm said. “I began in the late ’70s and early ’80s by really looking at plants and I started turning up things that were new to science; and that is pretty exciting, when you can find something that nobody’s ever seen before. It has been an obsession, just to get to every place I can, and try to find all the plants within the state.”

Project background

To catalog the plants of Nevada, Tiehm, who is one of the founding members and the president of the Nevada Native Plant Society, has been exploring the state from border to border. He is currently being assisted by Jan Nachlinger, a member of the Society.

Traveling by car, on foot, or even horseback, his approach is clear: he is trying to get to places where other collectors do not usually get to, those hard to reach, or to go to the same spots that someone already visited but in different times of the year.

Tiehm still finds previously undiscovered plants in Nevada. Because of his efforts, seven species of plants have been named after him. He wrote the book “Nevada Vascular Plant Types and Their Collectors.” His goal is to contribute new discoveries and corrections to the plant collection at the Museum at UNR, which now includes over 1,500 taxa (species and subspecies or varieties).

New discoveries

In planning a field expedition, Tiehm and Nachlinger take into account a number of things, but there is not a clear pattern to where they go.

“Sometimes we are trying to re-find a plant that was collected without fruit or flowers and we are not sure as to its identity,” Tiehm said. “Other times we pay attention to precipitation, especially in the lower elevation areas. The sandy deserts can be knee-deep in wildflowers during wet years and totally devoid of flowers in a dry year…Sometimes we just follow our noses. We will go to the foothills of a mountain and just poke around into canyons and see what we can find.”

Once in the collecting location, sometimes on hands and knees, they examine the area and plants that they recognize with ease. Sometimes, they find species they were not looking for nor were they expecting to see.

In September, during their last collecting trip of this year, they made new discoveries: two plants that were not known to be in Nevada. One was Muhlenbergia depauperata, a small annual grass known to reside in northern Mexico, Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah; and the second one was Hibiscus trionum, an introduced species from Southern Europe, North Africa, and Asia that has been found in most other US states.

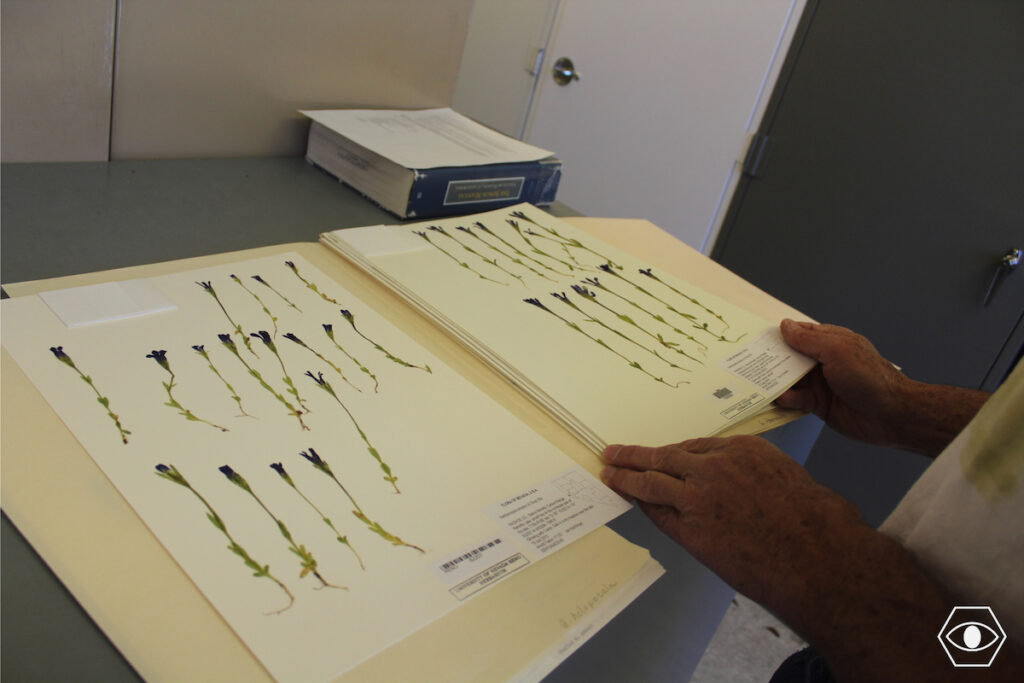

And that is how many discoveries are made. “We just happened to be in the right spot at the right moment,” Tiehm said. “Then, I take the plants, I press them and dry them and bring them back to the herbarium so we have a permanent record of it.”

Back at the herbarium, Tiehm identifies, labels, and glues them on white sheets of thick paper that will later fill the tens of cabinets in the Museum at UNR. He also sends specimens to other herbaria in Nevada and beyond.

He has also been revisiting literature and previous checklists and visiting already documented sites because mistakes in labeling and identifications have been made in the past by other collectors. He will include in this checklist an “excluded” list where these mistakes will be pointed out so that the errors are not perpetuated.

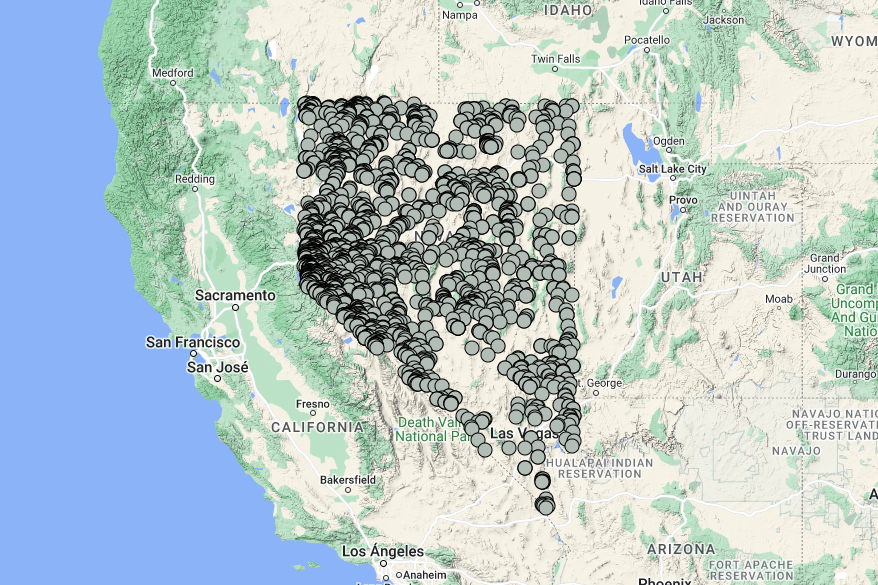

In this almost 50-year project, Tiehm has covered most of the state, except for the Nevada National Security Site in southeastern Nye County.

Why does this matter? What is next?

Almost five decades into the work, Tiehm still has the energy and enthusiasm to continue his project.

“I am going to continue doing this until I get so old and decrepit that I can’t go out in the field anymore,” Tiehm said. “There are already places I can’t get to now that I could get to earlier, but I still do it, I just get out and go. I gotta keep moving.”

He aims to have the checklist published within a year. An online database of UNR’s plant collection, including many specimens that Tiehm has collected, can be found on the Intermountain Region Herbarium Network website.

In the end, why does this checklist matter? According to Tiehm, it is important to collect and preserve plant samples the “old-fashioned way,” rather than modern methods such as DNA analysis only. One reason is that climate change is and will continue to affect plant populations in ways we don’t yet understand.

“We don’t know if some of these plants may become extinct and we would never have known they were here,” Tiehm said.

Having the actual plant samples is useful for students and researchers at UNR and outside. For example, the Director of the Museum of Natural History at UNR, Elizabeth Leger, Ph.D., did a study to see if “warming trends in the Great Basin have affected plant size by measuring specimens preserved on herbarium sheets collected between 1893 and 2011,” according to the paper. If UNR did not have this collection of plants, this and many other research questions could not be answered.

“Sometimes we do not truly know how these collections of animals and plants will be used by researchers and what questions are going to be asked in the future, but we keep the collections in good condition so they can ask those questions,” said Cynthia Scholl, education coordinator for the Museum.

The idea is then to keep as much information as possible to facilitate the resolution to those possible future queries: to learn about changes in shapes and body sizes; about past, present, or new diseases; about the interaction with plants and with ecosystems; and so on. The possibilities are infinite.

About UNR’s Museum of Natural History

In addition to the collection of plants, the Museum of Natural History at UNR also has a collection of animals, including, 2,330 birds, 3,800 mammals, 7,000 reptiles, 22,000 fish, and over 350,000 insects.

The lobby is organized by ecozones and provides colorful photos and information on the characteristic organisms, elevations, and temperatures of each: riparian and aquatic, alpine and subalpine, sagebrush steppe, and more. The Museum also has live animals for outreach and interactive activities, such as a rubber boa, alligator lizards, garter snakes, and endangered and threatened animals like native pupfish, Lahontan cutthroat trout, and Dixie Valley toad.

In the back of the museum, inside dozens of drawers, there are scientific specimens of animals kept with the skin and skull, stuffed with cotton, spread out for measurement, and numbered for future research; or exhibited in taxidermy form–meant to look alive.

When UNR is in session, in Fall and Spring, the lobby of the Museum is open Monday to Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. If you want to see the behind-the-scenes, you can schedule a tour. You do not need to have a large group. It is located inside the campus, in room 300 of the Max Fleischmann Agriculture building.

Learn more: https://www.unr.edu/natural-history