The Embalming

Halogen lights buzz overhead. The air is thick with a strange odor that lies somewhere between furniture polish and brown sugar. The latest donor to the Pennington Health Sciences anatomy lab lies supine on the surgical table. For just a moment, I thought I could see the donor’s chest lift, but it was only the push of the fluids up from the machine at his feet — which could’ve just as well have been a dialysis machine.

“You can see that there’s still some microbial activity happening in here,” says Lindsey Pisani, administrator of the University of Nevada Reno anatomical donation program, as she waves her hand over the green streaking on the man’s belly. “But the chemicals we’re pumping in will kill all of that.”

Health Hazards

Despite the challenges of the pandemic, the lab has worked to stay open for the educational benefit of its first-year medical students. For safety reasons, would-be body donors who passed away due to COVID-19 are not eligible to donate their bodies to the lab. However, the lab currently has enough resources for several students to collaborate on a donor, practicing the dissection at a safe distance from each other. Students dissect in a well-ventilated, open-floor surgical room, with specialized acoustic shields hanging above them to muffle cross-talk from other teams.

The process of funerary embalming is different than the preparation honored guests receive at the anatomy lab. At a funeral home, the decedent would receive just enough tinted embalming fluid to bring color to the hands and face — about a gallon and a half. Whereas at the lab, they receive up to eight.

“The idea is to preserve things down to the cellular level,” says Pisani. The lab also uses phenol, a sweet-smelling organic compound that occurs in the distillation of some whiskies, rather than other caustic and carcinogenic chemicals used in traditional embalmings.

The man on the table is surprisingly colorful. His face a splendid patchwork of red and white blotches; extremities wine-stained where the blood has settled. His abdomen is distended — but from the buildup of phenol in his body, rather than the decomposition I had expected. He is also naked — save for a discretionary cloth draped over his upper thighs, which also hides the embalming tube poking out of his leg, from which the phenol enters his femoral artery. The fluid does not escape his body, but for a pinprick on his chest, from where I can see tiny bubbles of embalming fluid emerging.

This is where his caretakers have drawn blood to test for syphilis, Hepatitis B & C, and HIV/AIDS. But these bloodborne diseases aren’t the only conditions the lab manager has to screen for — Pisani has already had to turn away two potential donors who passed away from COVID-19. For this reason, and despite the national excess mortality rate in the current year, many gross anatomy labs across the United States are experiencing a lull in whole body donations.

UNR Remains Stable through National Donor Shortage

This is Pisani’s first embalming in months — however, she attributes this to the natural ebb and flow of death in the area. She has accepted six more donors in short succession since the beginning of September. Despite these new challenges, the UNR gross anatomy lab has increased enrollments and received 15 more donors in 2020 than in 2019.

While a potential donor remains eligible if they’ve tested positive for the virus at some point in their life, they must have recovered from it if they are to pass muster. The health of the donors isn’t the only limiting factor: in years prior, potential guests of the lab must pass away within a 50-mile radius of Reno in order to be considered.

Walton’s Funeral Home, with locations in Carson City and Gardnerville, works with the lab to make the option for whole-body donation available to even more residents of Northern Nevada. Pisani is working to expand this radius even further by coordinating with a funeral home in Elko, nearly four hours away from campus.

Cadavers as Learning Tools

Pisani guides me to another corner of the room, where previously prepared donors lie in neat rows of boxes. She removes the cover from one to reveal a woman: glabrous and grey, looking altogether more like a movie prop than the man on the table. She is also bald.

“We shave their heads to give us better access to the brain during dissection. It also gives them some anonymity.”

Each year, the lab receives around 50 whole-body donations for the educational benefit of 70 first year UNR medical students. No longer the only whole-body anatomy lab in the state of Nevada, the lab also arranges donations for flagship anatomy programs at Truckee Meadows Community College and Western Nevada College. Learning gross anatomy is a fundamental milestone that lends medical students hands-on experience with the inner workings of the human body, as well as an understanding of how to detach from the act of surgery.

“(This) lab work is very social,” says Monica Becher, a second-year medical student at UNR. “It’s not just that we work in groups — whenever someone would find something unique during dissection, they would wave people over so we could learn about it together.”

Becher says the dissection lab was a meaningful shared experience that lab mates bonded over:

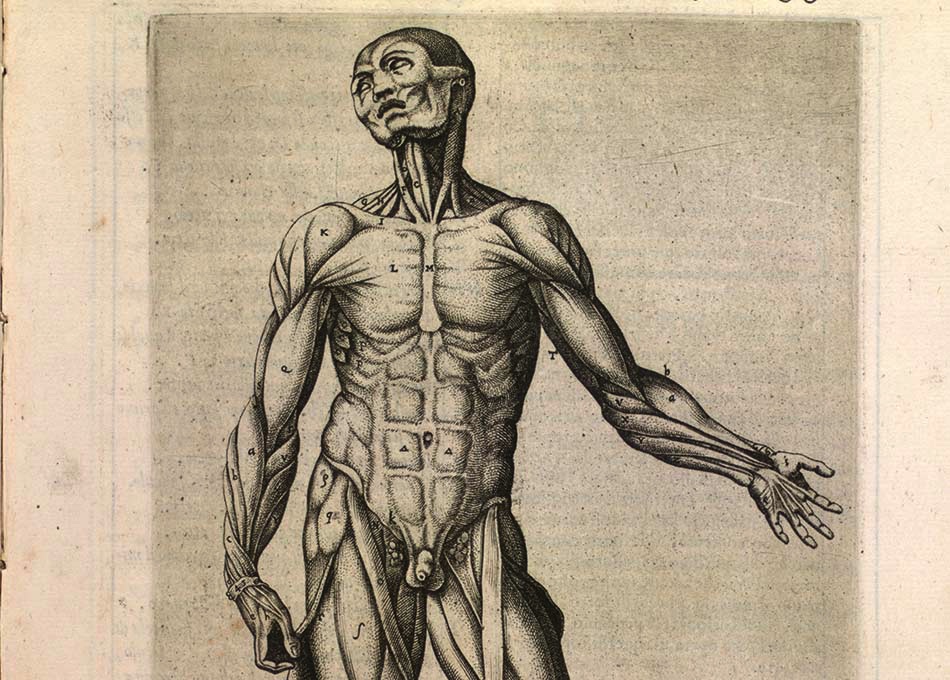

“It was one of our first experiences with what medicine looks like outside of the standardized knowledge you get in the classroom. Every anatomy textbook illustration looks pretty much the same. But in reality, everyone is different — and so are our bodies. This is something you don’t really get to see in a lecture hall.”

The First Patient

In the early stages of the pandemic, UNR medical students attended all of their lecture courses online, with the first-year gross anatomy lab being the sole exception.

“I suspect the lab experience held a somewhat different significance for our class than it has in years past,” says Becher. “I don’t think it would be exaggerating to say that gross anatomy was the core of our first year. With classes online due to the pandemic, the lab wasn’t just where we learned about the human body — it was also where we got to know our classmates. Without it, all the Zoom lectures would have been very isolating, especially for those of us who came in from out-of-town and didn’t already have friends in the class.”

Becher’s current clinical interests are in emergency medicine, but she intends to keep an open mind about her specialization until she starts rotations.

“In medical school, it’s common to refer to the donor you learn anatomy from as your first patient,” says Becher, “And while that might sound kind of morbid, I think it’s accurate. It’s our first opportunity to take our classroom knowledge and try and apply it to a real person and see how it fits, where it doesn’t, and learn from both of these things.”

Juan Valverde de Amusco c. 1560, via NIH Anatomia Collection.