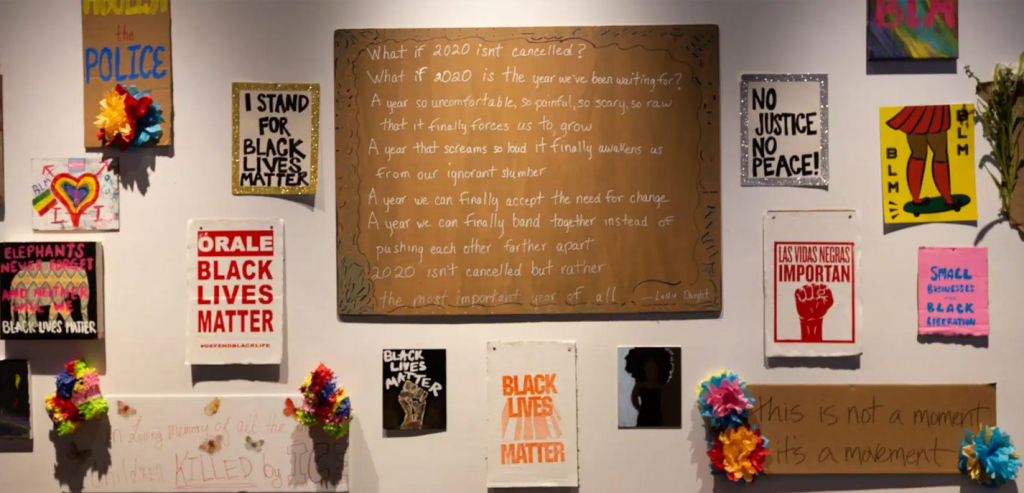

For months now, thousands around the world have taken to the streets amidst a global pandemic in response to racial injustice after the death of George Floyd, propelling their voices beyond masked faces. Racial tensions are hardly new, here or abroad; but for a country as diverse as the United States, racial discrimination can occur even before the visual cues of a face-to-face interaction.

While most Americans understand that judging people negatively based on how they look is wrong, bias against speech patterns not adhering to the local, dominant form is often not thought of as prejudice; nor is it explicitly defined under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And the result is a range of inequities in access to financial and educational opportunities, and quality health care.

To be clear, not all accents receive negative bias from the American public, but for those that do, it’s often amplified by the color of their speakers’ skin.

“Some African immigrants in the U.S. often tell me that it’s a bit harder for them because they are not only Black, but as soon as they open their mouth, they are also looked down upon because of their accent,” says Robert Apiyo, also known as Prince Nesta, a Kenyan native who moved to United States three years ago to attend graduate school.

Whether it’s called accent bias, language discrimination, or linguistic profiling — a term coined by Dr. John Baugh of Washington University in St. Louis, discrimination based on speech patterns can have real consequences that negatively impact lives.

One study published by Health Services Research found that callers seeking pediatric care who were perceived to be Black based on name or accent were less likely to be told that a medical clinic was accepting new patients. They were also more likely to experience delays until the medical office found out more about the patient, as in whether or not they receive subsidized medical coverage.

Given the rising racial disparities laid bare by COVID-19, society would do well to recognize that discrimination can come in the subtlest of forms.

These biases can be so infused in our psyches that studies have shown that people can hallucinate an accent that isn’t there just by seeing an ethnic looking face, says Dr. Valerie Fridland, a sociolinguist at the University of Nevada, Reno.

But while Americans may consider a French or British upper-class accent to be more cultured or intelligent, accents historically associated with the lower class — like the Southern drawl or African American Vernacular English — continue to be viewed unfavorably and stigmatized.

“We tend to think of dialects we don’t like as somehow being a bastardization of English — that it’s error prone and driven by mistakes, but in reality, language is just evolving and African American English actually has substrate influence from the African languages that form part of its basis,” Dr. Fridland says. “So it’s a really creative, innovative synthesis of an African structure and an English word and a sort of Creole-like formation. That’s not a mistake. In fact, it’s extremely sophisticated.”

Fridland states that society’s bias against African American Vernacular English is not with the language because there’s nothing wrong with the language. The language is actually completely, structurally intact and completely rule-governed. Instead, there is an underlying racism that bleeds into the language and culture that the speakers represent.

“A lot of misinformation about language is taught because what’s taught is the rule system of standard English as if it’s the only rule system,” Fridland adds. “In reality, it’s not. There are many, many rule systems. So I think linguistic insecurity often arises because we’re taught that there’s one norm and one form and if we don’t sound like that, then there’s something wrong with us.”

Bias exists around the world

Such stigmatization is not unique to the United States. In Kenya, a country that was under British rule from 1895 to 1963, Apiyo recounts that reggae emerged as one of the mediums to fight oppression. Inspired by reggae icon Bob Marley, Apiyo worked as a radio host for several stations in Nairobi. He relates that Kenyans who adhere to the Rastafari lifestyle and speak Jamaican Patois face stigmatization and are deemed to be of lower class or simpletons.

Speakers with a better comprehension of English language tinged with a foreign accent are often admired. In fact, Apiyo says that due to generations of conditioning under Western cultures, a sort of inferiority complex developed within Africans themselves. They tend to admire outside cultures such as music, lifestyle, fashion and languages more than their own.

Not only is speaking English or Swahili eloquently necessary for economic survival, it’s also become a measure of class and sophistication in the country. The more eloquently you speak these languages, the classier or more sophisticated you are deemed.

“If you can’t speak English or Swahili at all, you’re sadly viewed as uneducated or backward,” Apiyo continues, “and there are even a lot of folks who don’t even want to speak their own local languages, listen to local music, or eat their own local food.”

Deep divisions aside, Apiyo refuses to play the victim and is only more determined to spread his love for his African culture and roots.

What defines “sounding white”? What defines “sounding Black”?

Back in the United States, deep divisions also exist, but the narratives are different. For example, Tonya, a Black business owner in Reno, tells her story of growing up in San Francisco where she was accused by Black peers of speaking like white person.

“They’d be like, ‘Oh, you think you’re better than everybody? Why do you talk so white?’” Tonya says. “And it’s like, well, why can’t white people sound like me? Just because a Black person pronounces their words properly, it’s like they’re trying to be something that they’re not.”

“I remember telling a bunch of people, whether you realize it or not, we were kings and queens before anybody else was. So for you to walk around here and be less than what you are, you’ve given permission for people to do this to you. You don’t have to accept that. That’s not who you are. We were Nefertitis. We were Cleopatras. We were those people.”

Depending on who says it, Fanning’s experience could be one disdainful of Blacks who deviate from certain expectations or one that accuses her of “not being Black enough.” That discussion is fraught enough, but what does sounding ‘white’ even mean? Even linguists are hard-pressed to define it.

Even though white people speak many varieties of English, standard English has been most clearly associated with whiteness, says Dr. Ian Clayton, a phonologist at the University of Reno, Nevada. To the extent that society maintains that association, to speak the standard is to sound white.

“But it is crucial to recall that standard English is largely an artificial construct which has long functioned as an in-group/out-group test of class, education, and geographic origin, as well as ethnicity,” Clayton says.

“There is nothing inherently better about standard English compared to other varieties of the language. The features we associate with standard English are completely arbitrary. Nevertheless, any departures from that standard are highly salient to our ears, and are routinely exploited by listeners to place the speaker in one social group or another, often with negative and discriminatory results.”

Fridland says that noticing language differences is natural and something that all humans do. But when those differences are associated with negative traits, it becomes problematic.

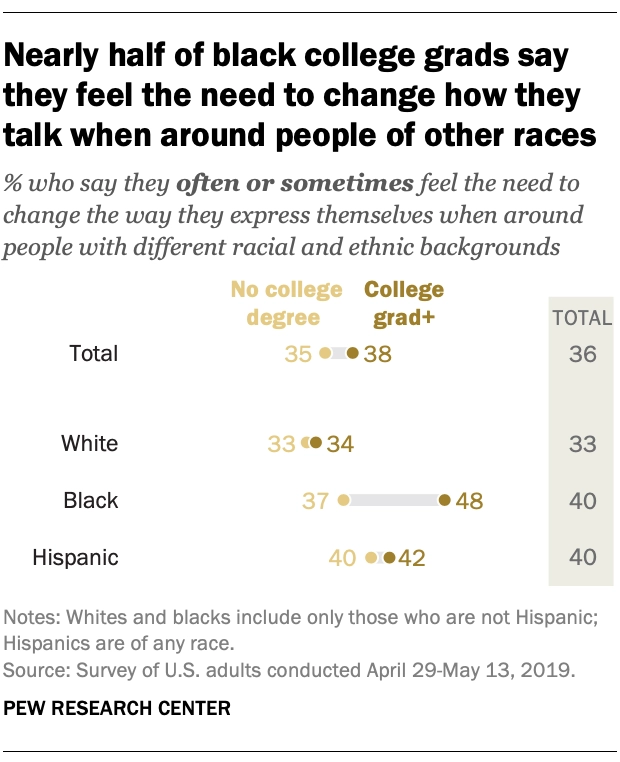

“When you look at how implicit bias has really worked for many, many decades without us even being aware of the reach that it has… We may often think that we are not racist — and we are not intentionally,” says Fridland, “but we still make these really low level judgements based on how we expect people to sound and when you do this systematically and in all different contexts over time, it does have a real effect on speakers, on people.”

“I think that there are really subtle ways that these kinds of bias get instantiated in our everyday lives without us even realizing,” says Fridland.

“If you just think about your own behavior when you encounter someone at a supermarket or a store, you may not think their ethnicity is impacting you, but maybe your language is still reflecting it. So it’s really important to think about how we might very subtly have these biases that then impact the way we respond to people.”