As COVID-19 deaths surpass 200,000 in the United States, UNR researchers have found some clues as to why the virus that causes COVID-19 is so contagious– and they’re discovering that it is mutating quickly. The researchers have studied the genetics of more than 7,400 samples of the virus SARS-CoV-2, collected from infected people all over Nevada.

The researchers are looking at how quickly the virus is mutating within the community, and trying to come up with an answer as to what those mutations will mean for the future of the virus.

“We did find certain mutations that were virtually unique to Nevada,” explains Director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory, Mark Pandori. “Now, we don’t know what that means, or why that’s the case, but we did see some, what we call ‘point mutations’.”

Pandori also says the team found a new mutation that did not originally exist in the virus when it came out of Asia. “It sort of evolved this point mutation, which might have something to do with the transmissibility of the virus and human host,” says Pandori.

In a case that made national news, the team of researchers discovered a 25-year-old individual with no significant underlying health conditions, who became infected twice. Pandori says the researchers ruled out the possibility that this person simply had the virus for a long time and it went dormant and then came back.

“The genetics of the two viruses for which they were positive were quite different. More different than could be explained by some kind of hidden infection that progressed across the time period. So it looks like they were infected by two distinct events,” explains Pandori.

“I want to warn you that this is not a common occurrence. This can happen, but it may not happen to many other people. Only some people,” says UNR virologist, Subhash Verma.

Both researchers say they’re not quite sure why a few people have contracted the virus twice: “We don’t know exactly and the answer seems very complex, one assumption is that antibodies generated from the first infection goes away (reduces significantly) in the two to three months after recovering from infection,” says Verma.

The team of researchers has collected over 160,000 COVID tests from Nevadans, and are working “to find out why certain people get more sick than others,” says Verma. This is something that has been covered by the media quite a bit recently.

“Some people are severely sick, some are healthier, some are asymptomatic.” Verma’s lab is studying patient nasal swabs from Washoe County Public Health Lab to try and find changes in the virus. “We thought that there might be some sort of mutation or change in the virus when it passes from one person to another.”

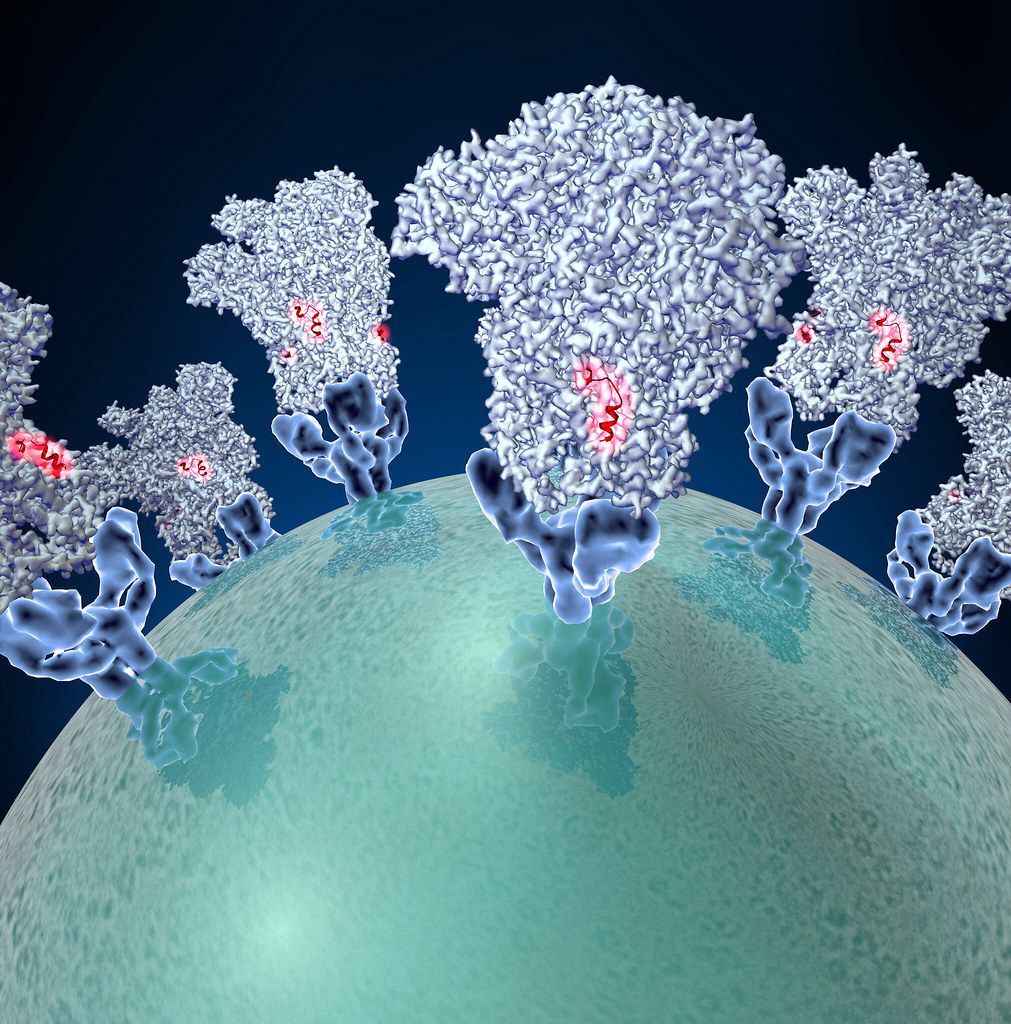

Another challenge is that researchers have found the virus to be incredibly infectious, in part because of its stability and due to the spike proteins and receptors it uses. The virus that causes COVID is called SARS-CoV-2 — Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome 2.

“SARS-CoV-2 is very effective at entering the cells for a couple of reasons. One reason is that the socket that it fits in perfectly matches on the surface of the receptors. Sometimes (viruses) have an imperfect match, but this receptor, which is there on SARS-CoV-2, it matches very strongly,” explains Verma.

“This virus has strong affinity, meaning once it attaches, it is not going to fall off,” clarifies Verma.

The virus is also very good at staying alive outside the human body. Even more so than other viruses, which makes it easier to infect more people.

“This virus is highly stable in the environment,” says Verma. “The virus can travel 26 feet from one person when they sneeze.”

“Also it can be in the air for up to ten minutes, or a little longer maybe. And also this virus can be alive on a surface – like if you sneeze on your armpit or elbow – then the virus will be there for sometime. This is compared with other viruses which die quickly when they are outside of the body. But this virus is more stable on clothing, on steel, on glass… everywhere.”

The researchers don’t know the importance of the Nevada-specific mutation yet, but they are conducting experiments to determine what this mutation will mean going forward.

“This will tell us whether the vaccines, which are in production, or testing phase, whether they will work for everybody or not. Whether they work for all the strains of the virus, or maybe you get some selective strain, which could be controlled by the vaccine.”

Verma says they’ll be continuing the study of viral DNA for a year or longer to see how the virus spreads and mutates. Then his lab plans to scale this information and create a model to share with “the entire country, the entire world – people can look at the data and see this mutation.”