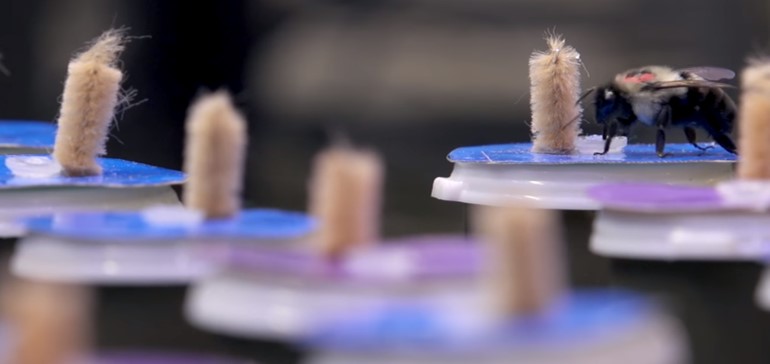

Photo credit: Felicity Muth.

No Hives, No Honey, No Recognition

With broadening public recognition of the declining global bee population and the mysterious Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), Save the Bees is a tagline you may have seen bandied about on commercial products like bumper stickers, mugs, hoodies, and especially reusable water bottles. This message often brings to mind the European honeybee, which may account for the recent boom in urban beekeeping.

But what many concerned parties who absorbed the message — and may have even donned the beekeeping veil — don’t understand is that the honeybee isn’t actually native to the Americas. It was introduced by European settlers in the 17th century, and is now essentially a feral species in our environment.

“I think that in the media and in advertising, we often really fixate on the honeybee, and that’s because we use it in our agriculture,” says Dr. Felicity Muth, a biologist specializing in bee cognition. “People who are really well-meaning will say, ‘Oh, I want to save the bees — I went and bought a load of honeybees.’ But actually, that’s kind of the last thing you want to do. It’s a bit like saying, ‘Oh, the birds are in decline. I went and bought a whole load of chickens.’ … So the drive for the book really came from just wanting people to know about all the other species.”

There are 4,000 species of native bee in North America — many of which, “aren’t even insects that people would recognize as bees,” says Muth. “They’re different colors. There are blue bees and green bees out there — teeny tiny bees that people would probably look at and probably think that they’re flies. But these are all bees that are really important for pollinating our native wildflowers and critical for our ecosystems.

“I work with bumblebees, which are called primitively eusocial. So, they’re not as social as honeybees — they don’t have thousands of individuals in a colony, but they do have hundreds of individuals in a colony — so they’re still very much a social species. In the lab, we work with one species, bombus impatiens [the Common eastern bumblebee], which is a species that is commonly used in agriculture.”

Muth also works with bee species in Northern Nevada and in Northern California, including the yellow-faced bumblebee, which “is largely black with — as you might guess — a little yellow face.”

Among its other important environmental functions, the yellow-faced bumblebee is used in commercial agriculture to pollinate plants like tomatoes, which honey bees can’t actually pollinate. While the ongoing loss of European honeybees portends great economic consequences, their native counterparts are indispensable to the health of North American ecosystems. Both are in decline due to accelerating threats from human development, pesticides, and climate change.

Alexa Landauer, illustrator, Am I Even A Bee?

Dr. Felicity Muth, author, Am I Even A Bee?

Bringing Science to Popular Audiences

Seeing how little attention the critical native bee species receive, Muth and her colleague decided to write and draw a book on bees. The scientists were intent on bringing melittology (the study of bees) to children’s literature in order to champion the importance of native bees and nurture an early sense of appreciation for the natural world.

“Am I Even a Bee?” is a children’s novel which debuted at Reno’s Sundance Books on April 16th. Illustrator Alexa Lindauer is a biologist specializing in amphibians and wildlife diseases who is working to restore populations of endangered frogs in California. Dr. Felicity Muth, the book’s author, is a professor of biology at the University of Texas at Austin. The two connected at the University of Nevada, Reno, where Muth was doing postdoctoral research at the Leonard Bumblebee Lab and Lindauer was working towards her Master’s degree in biology.

Neither of the two had ever imagined themselves collaborating on a book for young children. For Lindauer, the type of child-friendly art required by the project was a major departure from the styles she was familiar with.

“I think a lot of what I usually gravitated to was further into the fine arts, like portraiture and figure-drawing — I especially loved print-making,” says Lindauer.

“I really like the idea of using art to be able to share science. I think that any kind of output from scientific research can be really visually intriguing, and just that the world around us is pretty beautiful, unique and special when you stop and take a look, especially the little things. With this book, I think was really important to encourage kids — and really people of any age — to be observers of their natural world and engage them in science. To some people, the word science has become this big, scary buzzword — but all of it is just the process of the world around them and asking questions about it in a logical way.”

According to Muth, the idea for her book came to her completely spontaneously during a night of reflection on her career in scientific research:

“It kind of occurred to me that, as scientists, we tend to back ourselves deep into one particular topic. I felt like I could spend my whole life writing academic papers that I could probably boil down to two sentences. So I was really thinking about the impact you can have on the world as a scientist, and I came to the conclusion that I could probably have a lot more impact writing a children’s book than I would in a whole career in science.”

She immediately set to work on her manuscript — and finished the entirety of her first draft in a single hour.

“I guess I was in the process of having this… Well, I don’t want to call it a crisis!” says Muth. “I’ll call it… a revelation? And so I decided just to sit down and write this book for children. And it really just came naturally from that point.

“I had my manuscript in hand and I walked down to Sundance Books in Reno, which actually has a publishing branch. And what’s so wonderful about Reno — you know, the Biggest Little City in the World — is that I feel like it’s the place where you can actually go out and do that! I think if I’d been living in a big city, they would’ve told me to go away! So they took my manuscript and helped me re-frame it. They had me make it a little bit less dark than it was originally! They said that some of my ideas would be scary for children.”

Reha-bee-litating an Insect’s Image

Both scientists were challenged by the task of making the book palatable and entertaining for popular audiences, while also retaining scientific accuracy.

“Early on, we talked a lot about what we wanted to capture in the illustrations,” says Muth. “How to get that balance between them looking actually like the animal, but having them be expressive. For me, one of the most meaningful parts of this process was finding that balance between scientific accuracy and the sort of playful anthropomorphism that would appeal to kids.”

“I mean, insects can be scary. Bugs can be… kind of unappealing. We wanted to make them feel comfortable, approachable — even relatable. So [we pushed for] not giving them little human faces, but having, for example, their eyes on the sides of their heads like actual bees — but also giving them some character. But at the same time, it’s still somewhat scientific. Finding that balance with the bees and how they interact with their environment was an interesting challenge for me.”

In addition to bringing into focus some of the broadly-misunderstood aspects of “what it means to be a bee,” it is eminently important to Muth and Lindauer to use this creative medium to coax their audience into a deeper appreciation for the natural world.

“Science, art, and the outdoors have always been these three consistent pillars in my life,” says Lindauer. “And I usually have to put more effort into one — usually science — than into the other two, but art has always been a really important presence for me. I minored in visual arts in college and really loved the balance that my science courses and art courses provided me. But a lot of people don’t think there’s much overlap between the two, but I think there’s actually an incredible amount. I see that in their mutual focus on observation — in paying attention to the world around you — all the detail. These skills carry over to both the sciences and the arts in some incredibly important ways.

“And I think that kids are really some of the best scientists. They’re naturally curious, they’re really observant, and they ask a lot of questions. I hope this will get them to engage in the natural world — and maybe even their parents, too.”

What It Means To “Be” A Bee

The prognosis for native North American bees is bleak, which isn’t helped by the public’s confusion about their decline — even at the height of the “Save the Bees” zeitgeist. According to the Center for Biodiversity, 24% of endemic American bees (347 species) are imperiled, and 52% of the population is in decline (749 species). Muth and Lindauer hope that by the touching people’s imagination with their work, they can capture popular support for these misunderstood creatures.

“A lot of people feel hopeless about their ability to make a difference [in the environment],” says Lindauer. “But I think it’s worth it to encourage them. Especially in the case of the solitary bees — there are a lot of things people can do.”

“They can plant native gardens that encourage native pollinators, they can create really simple nesting habitats in their backyards, they can stop using pesticides. These are all really small, achievable things that can help increase insect diversity. I think getting popular audiences excited about the natural sciences and giving them the agency to say, ‘this is my planet, and I’m going to pay attention to it — even in small ways’ is really important.

Lindauer, whose body of work concerns the preservation of yellow-legged frogs in California and not native bees, says she was able to observe this within herself over the course of the project.

“Y’know, I’m a biologist — but I don’t study [this subject.] After I spent a lot of time learning about these bees and how best to draw and depict them accurately, I started noticing more bees and bee-mimics in the wild. And that was very special for me — there was definitely less swatting at things flying around my face while I’m eating lunch, and more observing and appreciating.”

Though the original inspiration for the work was to encourage biodiversity in the natural world, Muth and Lindauer maintain that their ultimate intent is just as much to support the diversity in their human audience.

“The way that this story is told is really just a message of diversity and the importance of not always being the same,” says Muth. “I wanted to say that it’s good to be different, just like the way there’s so many ways to be a bee.”

“Beyond that science angle, it’s important for kids to know that there are so many different ways to be a thing,” says Lindauer. “And that that can look like so many things that are beyond what we perceive as the status quo. I think this is a really important lesson for kids — as well as any other person at any age.”

“Am I Even a Bee?” authored by Felicity Muth, illustrated by Alexa Lindauer, and published by Baobab Press debuted at Sundance Books on April 16th and is available wherever books are sold near you.

Photo credit: Felicity Muth.