California is blazing with three of the largest wildfires in the state’s history, with much of the state facing smoke-filled skies and evacuation orders. In just seven days, the fires have charred nearly a million acres, according to Cal Fire, which is more than triple the area burned during a typical fire season (a little over 300,000 acres). In the Tahoe region and the Great Basin, firefighters are already exhausted as they gear up for more potential fires during a dry fall.

Truckee Meadows Fire Protection District [TMFPD] has at times been responding to multiple fires daily for consecutive days at a time. The Great Basin region is experiencing near record-low sagebrush moisture levels, which in turn is leading to higher-intensity and more frequent fires. Agencies are forecasting above-normal fire activity for the Great Basin for the remainder of August and into September.

“It’s exhausting, arduous work,” says Brian Bunn, fire captain in the training division for Truckee Meadows Fire and Rescue.

“With the rapid rate of spreads, we’re working at a superhero pace to [contain one fire] and then go to another [fire] and sometimes we’re going to three at the same time with limited resources. Firemen [typically would] get days off, but we have folks that haven’t been home in 14-18 days.”

Consequently, measures are being implemented by TMFPD to ensure that firefighters remain rested, healthy and ready for the next fire at a moment’s notice.

“District-wide we’ve taken what we call a ‘Safety Stand-down,” Bunn said. “So we put a lot of our regular duties on pause and we’re trying to get our guys to go back to the fire station to eat healthy, rest up, take lots of fluids and get ready for the next [fire].”

‘I don’t know how long we can keep up.’

Safety Stand-down measures are designed so that firefighters can reserve their energy for mission-critical efforts like responding to calls, making sure equipment is prepared and ensuring firefighters are physically ready. Typically, physical fitness training is part of a daily routine at many fire stations, but during Safety Stand-down, fitness training is temporarily suspended so that firefighters can rest between calls to action.

“We’re more physically ready to respond to these fires now because at this [current] pace, I don’t know how long we can [keep up],” Bunn said. “It’s been that incredible of a season and I’m speaking for Truckee Meadows Fire, we’ve run more than our fair share of calls and reducing any of those activities contributes to our response readiness.”

The high-intensity and high-frequency of fires can largely be attributed to the near record-low moisture levels in sagebrush within the Great Basin region, which includes southern Idaho, northern Arizona, Utah and all of Nevada.

“Our [regional] portion of sagebrush fuel moistures is seeing record-low fuel moisture,” Bunn said. “That means that there is more [sagebrush] readily available to burn and fires will get larger.”

Fires ignited in a desert sagebrush environment like Nevada’s can quickly spread with high winds, particularly because of the presence of dried out fine fuels like cheatgrass. When these fine fuels are ‘cured,’ or dried, they can serve as carriers for wildfire across sagebrush and consequently, large amounts of land, too.

“Fine fuel growth is a huge problem in the Great Basin, especially in Nevada,” says Gina McGuire Palma, meteorologist at Great Basin Coordination Center.

“It’s a fuel that will carry the fire from one sagebrush to another, so if you have a large fine fuel crop or a continuous bed of cheatgrass, that elevates fire concerns in Nevada because they’re pretty much like a ladder fuel, where it will transfer fire from one plant to another very quickly.”

Moisture levels within fine fuels like cheatgrass can fluctuate relatively quickly, which can further complicate predicting how susceptible they are to spreading fire across larger fuels like sagebrush.

“On a regular season basis alone, [cheatgrass] cures with a lack of moisture and direct sunlight,” Bunn said. “They are one-hour fuel moistures in that it basically takes one hour’s worth of moisture to get them to a non-combustible state and one hour of drying to be cured, which makes them readily available to burn.”

Sagebrush can dry into fire fuel within hours

Humidity, too, can also influence moisture levels of fine fuels and their susceptibility to spreading wildfire.

“[Humidity] has a very strong relationship to what’s called dead-fuel moisture, which is how dead fuels relate to the atmosphere,” says Dr. Tim Brown, research professor in climatology at the Desert Research Institute.

“So when atmospheric moisture increases, fuels will absorb that moisture and become more moist and the more moist they become, the less flammable they become. So under drier conditions, that fuel becomes more flammable and easier to ignite.”

Although Reno hasn’t been experiencing any unusual humidity levels this year, the summer months typically see lower levels of humidity compared to other parts of the year in high desert environments like Nevada’s.

“Here in the high desert we’re used to single-digit, low-teens relative humidity during the day, but we’re also used to relative humidity getting back above 30 or 40% at night,” McGuire Palma said. “So if you have very low relative humidity that continues overnight, that will further dry out your fuels.”

Cheatgrass dries out earlier than many desert flora, turning from green to brown/yellow in the spring; it then can ignite and burn incredibly quickly.

“In the spring, you’ll see [cheatgrass] start turning red and that is essentially the curing process [taking place],” Bunn said. “The moisture has gone out of the dirt to sustain the life of that grass. So [at first] it’s green, then turns purple or red and then that golden brown. Once you see that golden brown, that’s what we call the curated annual grass that is readily available for a combustion.”

A year of near-record low moisture levels

While annual grasses and fine fuels serve as the primary carrier for fires, it’s the near-record low moisture levels of sagebrush that is particularly concerning for regional fire agencies this year. Agencies like TMFPD rely on the National Fuel Moisture Database [NFMD], which provides users real-time information on moisture levels in both live and dead fuels across the United States. Launched in the early 2000s, the database helps fire agencies plan.

[Fire agencies] look at it pretty in-depth,” McGuire Palma said. “More often [the database] is part of fire danger operating plans, staffing and preparedness [plans]. As far as the on-the-ground firefighters, they’re probably hearing a lot of information that stems from people who are utilizing this page and I’m sure they are given all the latest information on fire danger, and fuel moisture is a big part of that.”

The database is updated frequently: samples are taken by fuel specialists on a bi-weekly basis from mid-April to October. Samples are not taken in the winter and early spring months, as these fuels return to their dormant state during that time. However, changing weather patterns in the late spring and summer can complicate the sampling process as samples can only be accurately counted if it’s been dry for 24 hours.

Fuel specialists gather samples by cutting off branches of fuels like sagebrush, before drying them out in a specialized oven.

“The moisture remaining [after the drying process] is the moisture content of the fuel because there’s always moisture content in fuel,” McGuire Palma said. “Even a dead fuel has some sort of moisture it’s retaining, but live-fuels certainly retain a lot more moisture. So when you’re looking at the percentages on the NFMD, what that’s showing you is really how much moisture is left in the fuel.”

Low snowpack contributed to dry sagebrush this summer

While measurements in sagebrush moisture levels across Western Nevada have varied this year, several areas surrounding Reno have registered near record-lows compared to their historical averages. One factor for these low measurements could be the lack of snowpack seen this past winter.

“Our larger fuels and our timber areas are quite a bit drier than what we’ve normally seen,” McGuire Palma said. “When we come off of the winter, snowpack is [an indicator of] where we can expect our fuels to go during the fire season, because the amount of snow will impact how long it takes for fuels to become critically dry.”

“We didn’t have a huge snowpack this past winter, so as expected we are seeing our larger fuels a little bit drier than normal.”

Moisture levels on the database are presented as a percentage scale for fire behavior, with lower percentages showing drier fuels that pose a greater risk for wildfire spread. Breaking points for categories of fire behavior are considered at 25% intervals.

“As you go down in fuel moisture percentage, the fire behavior will go up,” says McGuire Palma.

“So 75-100% is one category of extreme fire behavior, 100-125% would be another category of high fire behavior. Get up above 126-150% and that’s moderate [fire behavior]. So the numbers are very important because it will tell firefighters what type of fire behavior they can expect based on the live-fuel moisture levels.”

At one sampling location in Doyle, California, located just under 30 miles west of Pyramid Lake, the annual average value of fuel moisture in sagebrush registers at around 115%.

“The record low [for Doyle] from July 1st is about 60%, and our current year for July 1st is sitting at about 80%, so darn near meeting the lowest record,” Bunn said. “If we go back to June 15th, we were sitting at about 105% in the current year, and the record low is about 98%.”

The most recent measurements for Doyle are at 75% for July 15th and 72% for August 1st, respectively. Both measurements are at extreme levels of fire behavior.

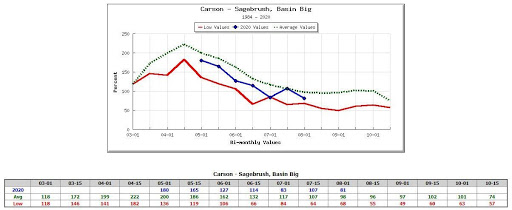

Additionally, Carson is also seeing low moisture levels in sagebrush, where the annual average typically registers at about 135%. Early August sampling has shown sagebrush moisture levels are back to the near record-lows. This could be behind the Rock Farm fire that occurred in South Reno in late July.

Chart courtesy of NFMD website.

Low measurements in sagebrush moisture levels make it critical to contain the fire early. Initial attack is considered to be the operational period within the first 24 hours a call is received and a crew is dispatched. If a fire is not contained within that first operational period, an extended attack is then implemented in cooperation with other regional agencies.

However, the rate at which TMFPD has had to respond to fires has already been physically demanding in a fire season that has still yet to reach its peak. Although the typical fire season is from the beginning of June to the middle of September, the risk of wildfires breaking out can happen at any time throughout the year, as long as conditions are right.

“It’s been a non-typical [season] in that we are responding to more fires every day that are getting bigger, faster,” Bunn said. “Every one of our fires in our county have been contained within that 24 to 36 hour period thus far, but you can have a catastrophic fire in any given month, on any given day. It’s all about conditions and the fuel moistures being readily available for burning hotter and burning faster with bigger flames.”

The Predictive Services Outlook forecasts above-normal fire activity for the Great Basin for the remainder of August and into September.

However, in a worst-case scenario that a fire spreads rapidly and cannot be contained, federal resources can be called in to support containment efforts. Although the rate at which the TMFPD crews are responding to fires has been unusually high, they have yet to call in for that federal support. That doesn’t mean, however, that they won’t need federal support in the future.

“My concern is sustainability: ‘How long can we keep doing this day in and day out before our staff is physically not capable?’” Bunn said. “But the great news is that we report to a National Incident Management System, so we have the ability to call in resources throughout the country to come help us [if needed].”

In the meantime, by implementing Safety Stand-down measures and monitoring the moisture levels of sagebrush listed on the NFMD, fire agencies like TMFPD will continue to be prepared for the remainder of the fire season.