It’s November 2075, and all the makings of a monster storm are brewing in the western Pacific Ocean. By February, a river of warmish rain will pummel the Sierra Nevada. In the midst of the century’s fourth 500-year drought, water agency managers know they need that precious liquid for summer. Thanks to research decades earlier, they also know within a smidge how much rain will fall and how much water will pour off the high mountains. That tells them how much to let gush out of their reservoirs to make room for what’s coming. And, with their grandparents’ memories of the disastrous winter of ’17 oft retold — about the year that heavy snows followed by a warm winter rain created huge early run-off, threatening California’s Oroville Dam with collapse — these managers also alert local emergency officials, who start preparations months ahead of potential calamity.

Hydrologist Adrian Harpold of the University of Nevada, Reno, thinks a lot about that 2075 scenario. He and teammates are working toward new tools to forecast wintertime storms and monitor run-off flowing downstream amid a warming climate. Their work includes tracking signals as seemingly small as the sap flowing up trees.

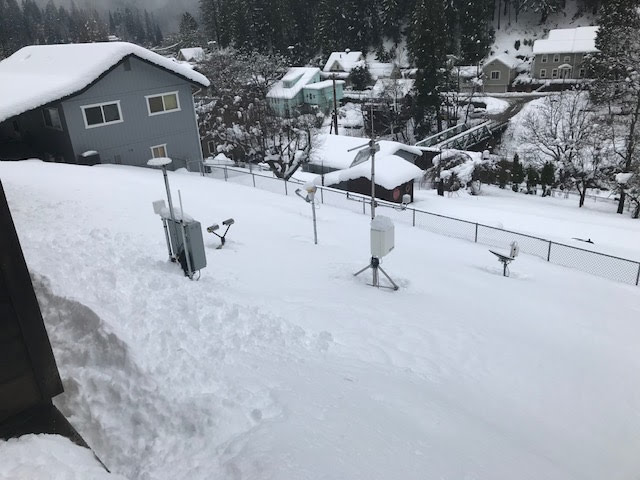

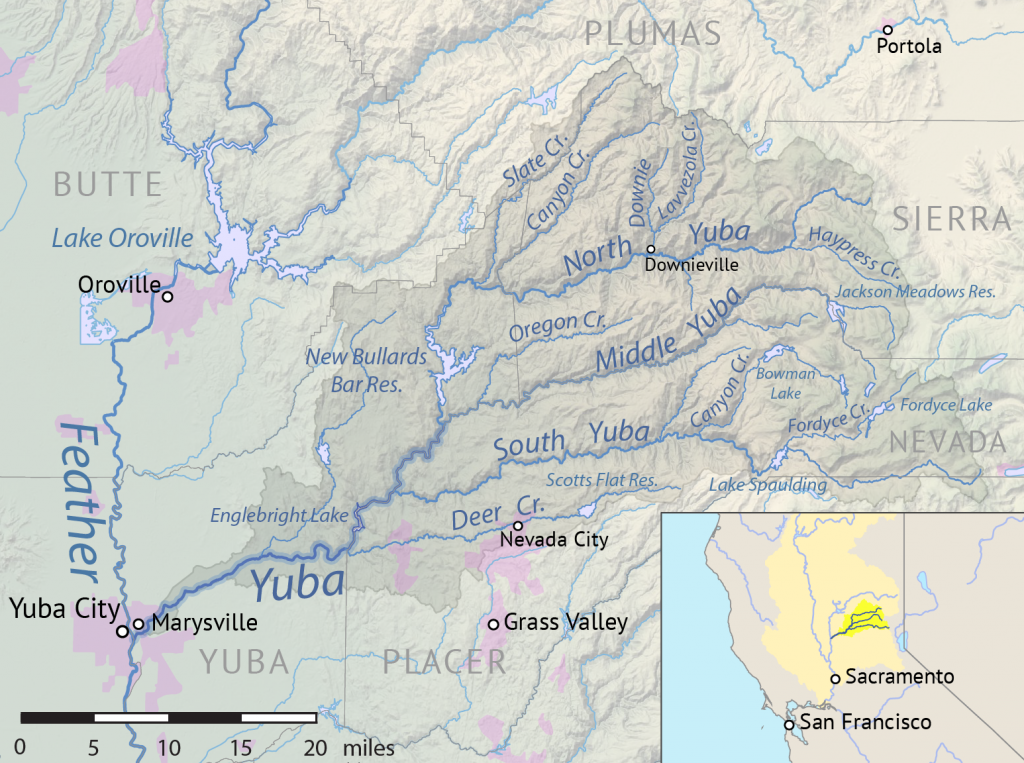

These studies — part of the Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations project– could lead to changes in rules for federally controlled reservoirs, including Boca, Stampede and Prosser, which store water for Reno and northern Nevada. The rules tell water managers how much they can keep in reservoirs during winter. Usually, water levels stay pretty low. The idea is to leave room to capture a sudden surge of wintertime run-off, minimizing disastrous floods.

Changing the rules just a little would let reservoirs keep more of that water, adapting to the shifts in the West’s water cycle caused by global warming. Yet, the rules would still protect downstream communities from floods, a recent experiment shows.

And when it comes to managing water in the American West, “a marginal improvement is worth a lot of money,” Harpold said. “A mistake is going to be on the national news.”

Experiment: 20 percent more water saved

Those reservoir-level rules were last updated decades ago, said Anna Wilson of the Scripps Institution for Oceanography. Since then, water managers and researchers have learned a lot more about the patterns of the West’s highly variable water cycle. In addition, warming climate has shifted much of wintertime’s snow to rain and made the rules inefficient. Some winters, water district managers have to let early run-off spill over and flow away, so they can keep reservoir levels at the federally required low level. Come summer, if it’s hot and dry like this year, they may wish they had that water.

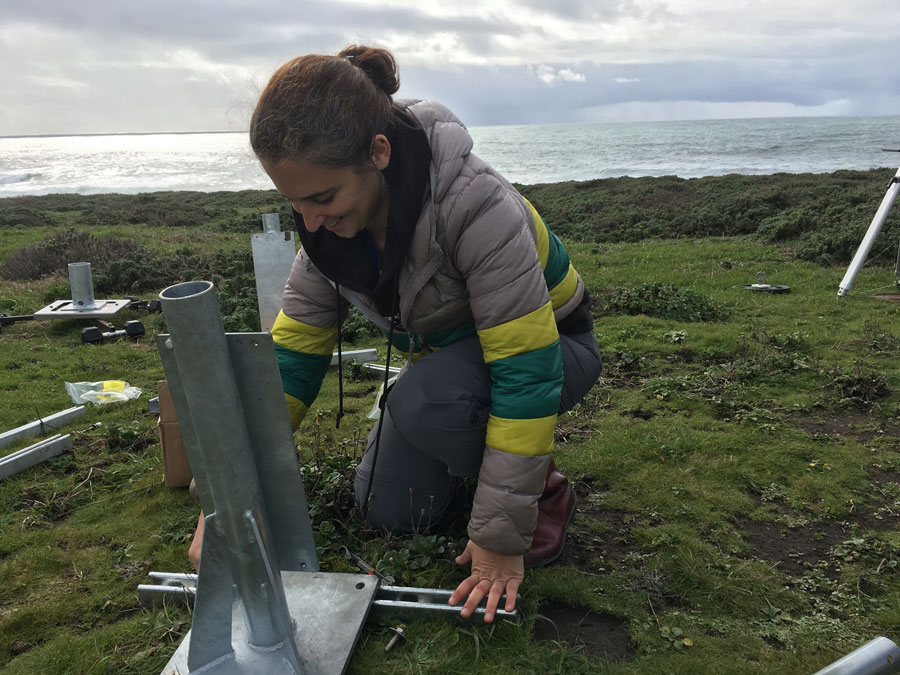

Federal officials see the value of a rule change, but it makes them nervous. “There’s no tolerance for the risk of flooding,” said Wilson. She’s an environmental engineer for Scripps’ Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes. She’s working with Harpold and others across the West to put together the puzzle pieces to create a forecasting tool leading to that 2075 scenario.

The researchers came up with a new reservoir water-level rule and tested it in 2019. Their guinea pig is Lake Mendocino, which stores water from the Russian River basin toward the central California Coast.

“We showed they were able to keep about 20 percent more water in the reservoir over what they would have had with the existing” federal rule, Wilson said. That amounts to 11,000 acre-feet of fluid, enough to supply 11,000 average households for a year. “That much water was there at the end of the water year (on Sept. 30), which is very exciting.”

She described the collaboration as “huge,” including the United States Army Corps of Engineers and local water agencies. It was led by by Scripps weather center Director Marty Ralph and Sonoma Water Agency Chief Engineer Jay Jasperse.

On the path to the Sierra Nevada

The project to create a new water-level rule is called Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations. Wilson and collaborators are expanding the FIRO tests to a second reservoir in southern California and a third in the Feather-Yuba basin, which embraces Lake Oroville.

“We’re now on the path,” Harpold said. “We’re getting the tools better; we’re getting the pieces better. It’ll probably take 10 years to take this to the Sierras.”

That will be an important jump. Sierra Nevada snow provides about 60 percent of water for California, as well as significant liquid for the greater Reno area and northwestern Nevada. So, if experiments like the Russian River FIRO trial could create decision support tools for managing Sierra Nevada water more efficiently, the pay-off would be huge.

“There are a lot of stressors on our infrastructure now,” Wilson said. “Instead of building new infrastructure, can we use our existing infrastructure better and more efficiently?”

The answer, they hope, will be ‘yes.’