This story was shared with permission from KUNR Public Radio. For an audio version of the story, please visit the KUNR website.

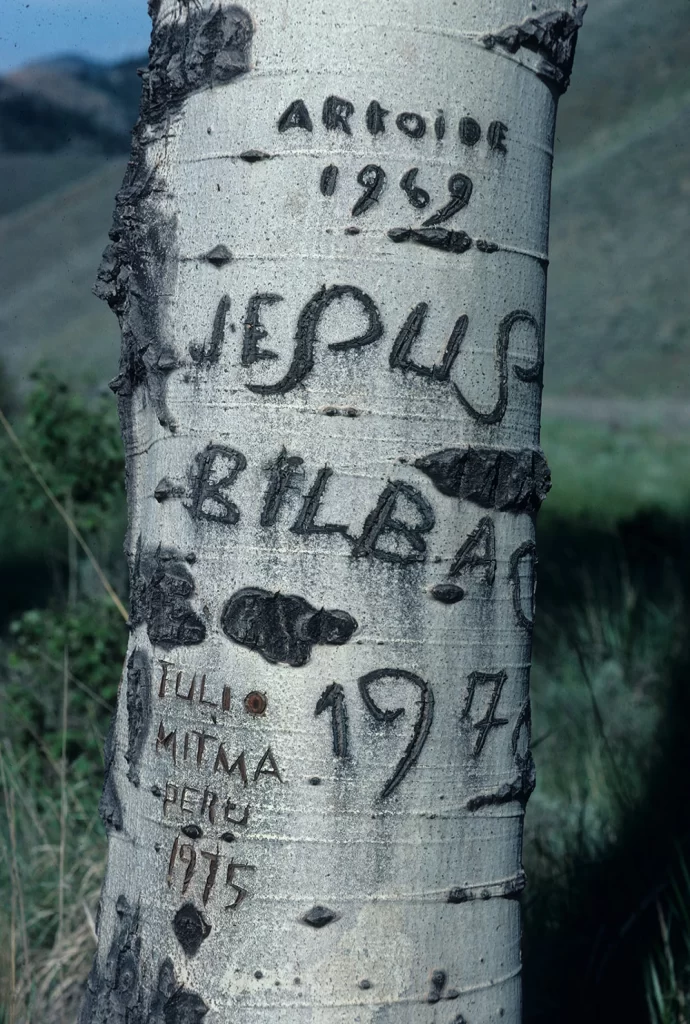

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the American West was home to millions of sheep and their Basque sheepherders. High in the mountains, the evidence of their history remains etched in Aspen trees through carvings known as arborglyphs, but as the trees reach the end of their life cycle, these cultural treasures also disappear.

In an effort to preserve and document these windows into the past, Basque history and culture experts have joined forces with media professionals and scientists to create The Arborglyph Collaborative, or Lertxun-Marrak, as it is known in Basque. Arborglyphs serve as an important record of what life was like for the sheepherders, said Iñaki Arrieta Baro, head of the Jon Bilbao Basque Library at the University of Nevada, Reno.

“It’s a way of expressing. We humans, we need to communicate somehow, we need to tell to ourselves or to others how we feel, and how we are doing during the day. And one of the ways that they find to do that was creating the tree carvings,” Baro said.

Common arborglyphs contain dates and names of those who carved them, as well as images of home, Basque symbols, and women.

The carvings had to be delicately created by drawing lines with a knife in the light-colored bark of the Aspen trees, Baro said. But they would not appear until much later when the tree had healed, creating a dark, raised scar. He likened it to leaving a message in a bottle, ones which now serve as an important historical record.

“That sheepherding experience is related to that solitude. It’s better documented through these tree carvings than anything else, because we are seeing that record of what they were going through while they were by themselves,” Baro said.

In 2023, a planning grant was awarded to the University of Nevada, Reno, Boise State University, and California State University Bakersfield to create the Collaborative. Its goal is to connect people and organizations and create systems for documenting the arborglyphs.

There are unique challenges that come with documenting the arborglyphs, Baro said. The carvings change size as the tree grows, and often wrap around the tree, so a two-dimensional photograph has its drawbacks.

And that’s where Daniel Fergus, director of digital media technology at the University of Nevada, Reno’s library, comes in. He is working with the Collaborative using a new piece of technology to document the trees.

“The digitization process that we’re currently using is called photogrammetry. And basically, all it is is taking a bunch of photos in a circle around an object, putting it through software, which then combines it all together into a three-dimensional object,” Fergus said.

This technology can be used with an iPad or even a smartphone, which is important because Fergus hopes that anyone with a phone will be able to use this technology to document some of the thousands of tree carvings.

Outside the media center, Fergus demonstrated the process using an iPad.

“So I’m just going to circle around the tree and I have to move when we do it. But I’m just going to take a photo, circle around – one, two, three, four…” Fergus said, as he snapped photos.

Once he captured at least 20, he uploaded them into a software program. Within minutes, a 3D model appeared on the screen that could be clicked on and spun around. This will open up a world of opportunities to display and interact with the tree models using augmented reality, Fergus said.

“There’s becoming less and less arborglyphs out there. One of the preeminent scholars and experts in arborglyphs, Joxe Mallea, he had mentioned that he had documented 20,000 across the West Coast. And he said, ‘It’s just the tip of the iceberg.’ But that was many years ago, and these trees are dying. So the oldest ones no longer exist,” Fergus said.

Climate change, wildfires, and the natural life cycle of the trees are some of the reasons that the Aspen trees are dying, he said.

Alexandra Urza, an ecologist working with the Collaborative, echoed Fergus’ concern. She said that climate change is impacting Aspen mortality, but that there is another factor they are running into – time.

“A lot of the kind of peak of Basque sheepherding activity, and when the Aspen tree carvings started, was around 130 years ago, which kind of perfectly coincides with the lifespan of Aspen trees,” Urza said.

Aspen trees don’t often live longer than 130 to 150 years.

Although The Arborglyph Collaborative is still in its planning phases, it holds a promise to preserve this tradition that is unique to Basque sheepherding in the West.

“The trees themselves are ephemeral. So we have these cultural artifacts that are on this ephemeral surface,” said Urza. “It’s a little bit like disappearing ink in a way, and so I think it really is the right moment to really try to document those before they’re lost.”

Kat Fulwider is the 2024 spring intern for KUNR and the Hitchcock Project for Visualizing Science.