I never knew exactly what I wanted to be when I grew up. When I was little, it was a doctor. Then it was a photojournalist. Then a professional skier, international correspondent, astronaut, and back to doctor.

When choosing a path of study in college, the question was always “science or humanities”— “this or that.” The combination of the two was not something that was advertised to students as an option. You either have a science and math brain, or you have an English and history brain. My advisor told me to choose.

I studied geoscience in college because I thought it would set me up well to go into any science field of my choosing – once I knew what I wanted to choose. I believed I had a science and math brain.

After college, still lost over what I wanted to do, I spent four years traveling the world as a professional athlete, supporting my training and travels by writing for outdoor industry magazines. My Bachelor’s in Geoscience certificate sat in a closet at my parent’s house, collecting dust. According to my 50+ published articles, I also have a humanities brain.

The thought of combining the two – science and writing – didn’t enter my mind until the COVID-19 pandemic began infiltrating lives across the world. The mass amount of scientific information that needed to be communicated to the public to keep a safe and healthy population was overwhelming. And, unfortunately, the mass amount of misinformation that spread about the science behind COVID-19 was also overwhelming.

Seeing this need for communicators who could clearly and effectively explain scientific concepts to the public, I found myself applying to graduate programs in journalism and science writing.

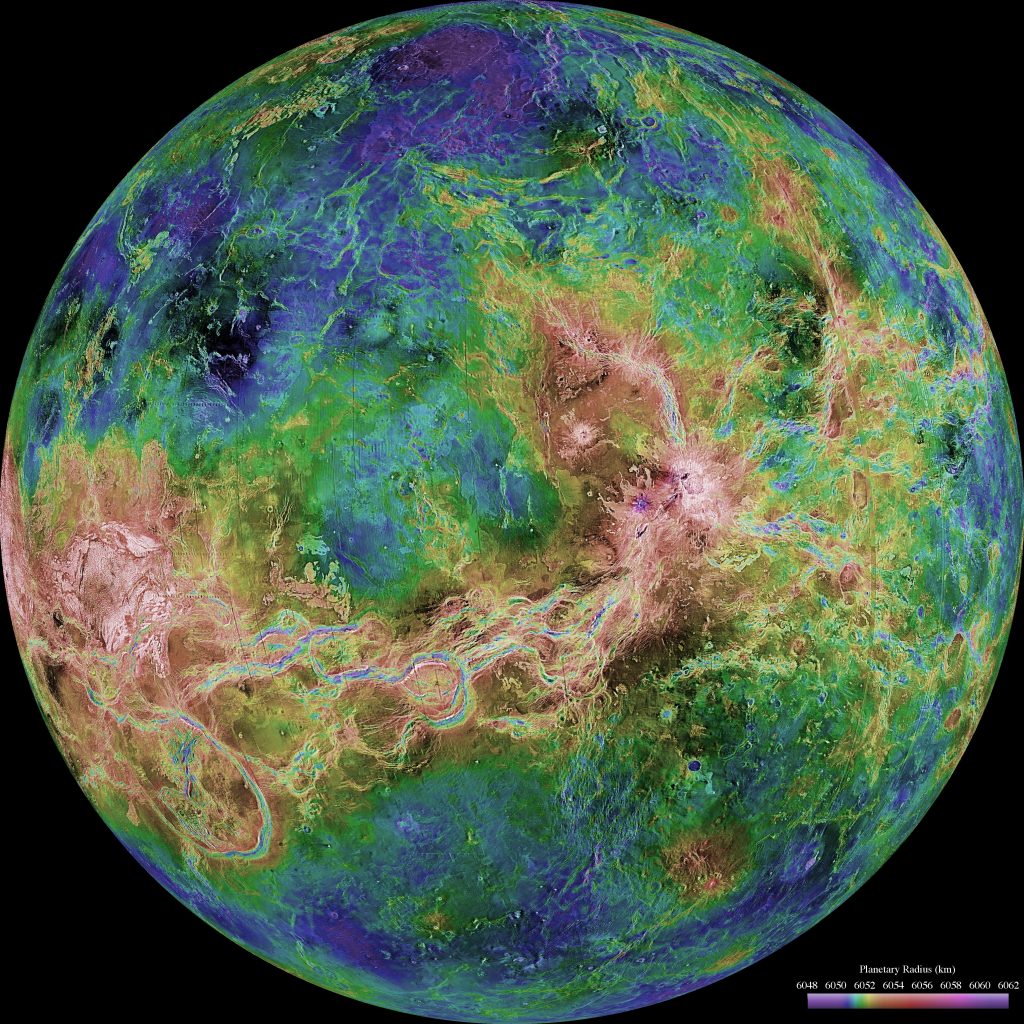

Fast-forward one year and I found myself sitting in a NASA lecture about growing crops in space, and learning about space bees – the future pollinators of Mars. Out of some crazy combination of experience and luck, I had somehow managed to land one of fifteen coveted summer intern spots on NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s communications team. Paired with a science writing mentor in Planetary Sciences, my job was to write articles about the DAVINCI mission to Venus.

I was to write a “10 Mysteries of Venus” piece, explaining ten unsolved scientific mysteries about the planet that the DAVINCI mission is hoping to solve. I was also tasked with writing features about the seven instruments on the DAVINCI spacecraft. I was to write about what they do and the science behind how they do it.

The catch?

I had to write everything in a way that an eighth grader could understand.

How do you explain what a quadrupole mass spectrometer is to someone who never completed high school chemistry and doesn’t know the definition of an isotope? How do you discuss the possibility of plate tectonics on Venus with someone who never took Geology 101? And how can you clearly explain the purpose of a bipropellant system to someone without any prior knowledge of the basic laws of physics?

I soon found myself wracking my brain for creative ways to translate complex scientific concepts into easy-to-understand language.

For example:

A quadrupole mass spectrometer is the “nose” of a scientific instrument. It sniffs a small portion of the gas, and separates the gas into its individual components.

Plate tectonics can be explained by talking about Earth’s crust as being the host of a network of thin, eggshell-like plates jostling around on the planet’s surface in constant horizontal motion.

And a bipropellant system is a system that uses both fuel and oxygen to create propulsive force. Bi = two, so the system uses two propellants.

I was using the “humanities” and the “science” sections of my brain simultaneously, and in doing so, proving wrong all the college advisors who told me to choose between the two.

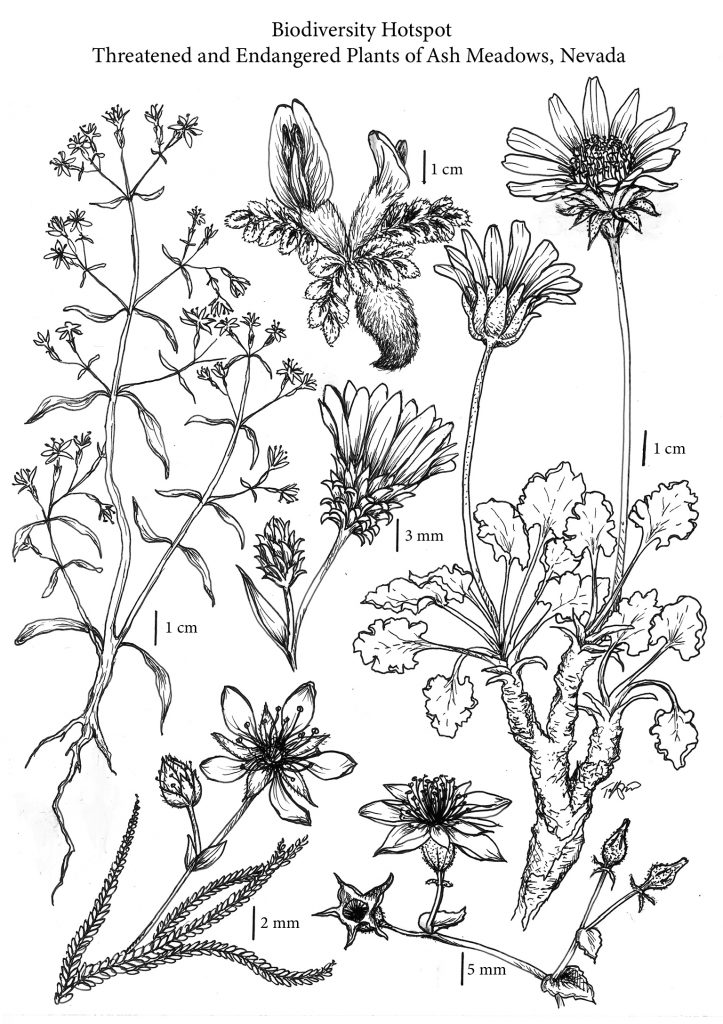

I’m now in the last semester of my journalism master’s program and working on a social media campaign on women in STEM fields. I recently had the pleasure of meeting with Tiffany Pereira, an ecologist and scientific illustrator for the Desert Research Institute. I learned that she too, was told she had to choose. “Science or art,” was what her art teacher told her. She couldn’t possibly do both. But she chose both. And she made a career of it.

Now Pereira is one of the few researchers specializing in science communication through art, a field that is utilized anytime you open up a bird identification book or watch an animation about the planets in the solar system.

As I reflect on how I landed here as a science journalist, I can’t help but think about the future and where this career might take me. Maybe I’ll be back at NASA working as a science writer. Maybe I’ll go into river conservation, working to communicate environmental issues to American voters. Maybe I’ll write for National Geographic! Or maybe I’ll teach. And if I teach, you can be sure I won’t be telling my students to choose between science and humanities.