The Great(er) Migration

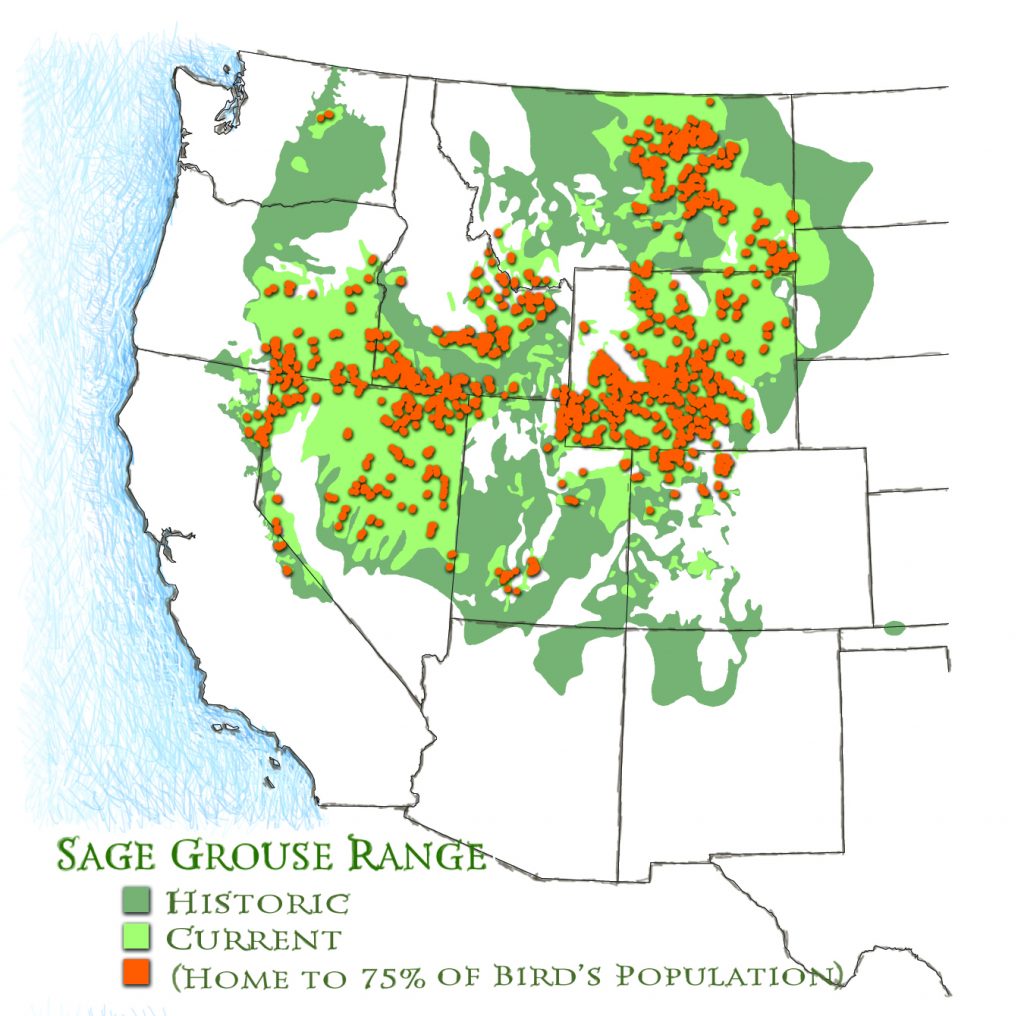

As winter creeps in, Greater sage grouse populations in the Great Basin area are transitioning from the wet meadows where they rear their broods to their sagebrush habitat, for which they are named. These icons of the West rely on a diversity of habitat including open plains, mountain ranges, riparian wetlands, and most importantly, sagebrush.

In the spring, grouse return to their breeding grounds (called “leks”), where they perform courtship rituals. These leks are usually sparsely vegetated, so that the hens and males can see each other clearly. As these upland leks dry out in the summer, grouse chicks will follow their mothers into their riparian “brood-rearing” habitat. In this season, the families seek out any green, wet places where they might forage for soft, protein-rich foods — like insects and forbs. By October, most grouse will have left these areas for their winter ranges in order to avoid the snow. The birds require access to each of these habitats in order to maintain a healthy population. If their range is fractured, their chances for survival suffer.

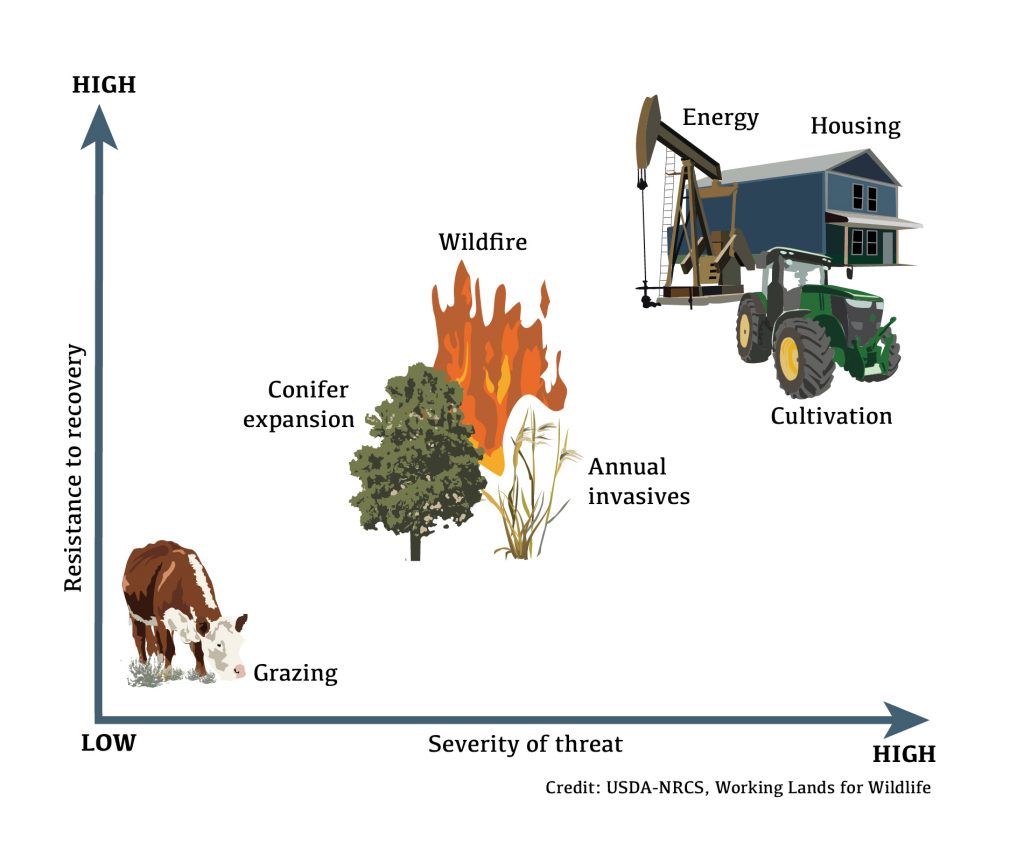

As of the time of publication, grouse are still moving down from higher elevations to lower elevations. Though human activity— such as mining, oil extraction, livestock grazing, unmarked fences, and construction— has limited their ability to safely travel through their seasonal migration pathways. This steady degradation of their original habitat has sent the grouse into a decades-long decline.

By some estimates, there were as many as 16 million sage grouse in North America as early as the 1960s. In recent decades, however, these numbers have plummeted to 200,000-500,000. In spite of this grim downturn, the species remains “unlisted” and beyond the protection of the Endangered Species Act due to various political obstructions.

Photo courtesy of Jeremy Roberts, Conservation Media.

As it stands, the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NCRS) estimates that half of all remaining sage grouse live on private lands — which carry with them the risk of habitat degradation through human activity and development. In an effort to protect the birds where they live, a government organization is partnering with ranchers in the bi-state area to reduce habitat fragmentation along their migration pathways — and they’ve just begun their most critical season in years.

The Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI) is an effort by the NCRS that works with ranchers and other landowners to protect and allow the birds access to critical sage grouse habitat to address conservation issues on sage grouse habitat. They locate the owners of “ecologically valuable land” (who are most often livestock ranchers) in an attempt to coordinate with them to restore the rangeland.

Some of the ways the program helps restore sage grouse habitat include: livestock grazing areas infringing on breeding and brood-rearing grounds, grouse colliding with unmarked fences, and the encroachment of invasive grasses and conifers.

Historically speaking, the nature of the relationship between ranchers and government conservation initiatives is fraught — especially here in Nevada. That’s why the SGI Outcomes Team believes that they’ll have greater success through collaboration, rather than coercion. As such, cooperation between SGI and the ranchers they work with is voluntary — not regulatory, as which tends to be the case with the offices of the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency, and similar government organizations.

Thad Heater, a biologist on the initiative’s Conservation Outcomes Team, says that the ranchers he works with appreciate the opportunity to learn how to help the bird:

“We help the ranchers deal with the resource concerns on their land and help them comply with the state and federal laws,” says Heater. “Which also serves to benefit wildlife and the natural resources on the landscape. So, essentially: the ranchers can stay in business, but we come in and provide education in the field so they can also make improvements to the resources over time. It’s about balancing our needs for the future with sustainable agriculture.”

SGI’s Two-Pronged Approach

Ranchers are incentivized with easements — government stipends — to maintain their land in ways that promote grouse habitat. These easements aren’t just designed to make up for lost profits from altering their most cost-efficient grazing patterns and irrigation systems. The extra income also incentivizes ranchers to hold on to their properties — rather than selling them to developers, who often have little investment in the preservation of the land.

“The conservation easements on these migration pathways, as well as other habitat areas for sage grouse, have been very key,” says Heater. “We’ve done a bunch of easements over in the bi-state area that are protecting and keeping that landscape intact down there because — I mean, c’mon — it’s like prime area for development. There were developers who wanted to take important areas near Minden and Gardnerville and the Sweetwater Summit, as well as Bridgeport Valley over on the California side. They really wanted to buy those ranches to convert them into condos and golf courses, and all sorts of other things.”

Heater says participating ranchers “didn’t want to see that. They wanted to keep their land intact. Without their participation, development would’ve fragmented the habitat on the landscape — and to a tremendous degree. So, depending on where you are, preserving those migratory corridors is also protecting key core habitat. And that’s what we’ve done since the inception of the Sage Grouse Initiative.”

Over the course of the last decade, SGI has cooperated with 2,366 ranchers and conserved almost 8.6 million acres of rangeland habitat. Despite these compounding victories for grouse conservation, the quantity of birds recovered by their efforts is difficult to measure. Header says that this is because of the distinctly cyclic nature of sage grouse populations.

“The sage grouse — they go up and down a bit,” says Heater. “It somewhat depends on their hatch in the spring, because ravens and other birds prey on them. But sometimes the particularly cold, wet springs we get are detrimental to them as well. In 2016, we had some of the highest numbers across the West for sage grouse in recent history — and those numbers have shot up about 27% each year since then. But since it hit that peak, it’s started going the other way — and, well, they’re cyclic. So, more recently, they’ve kinda taken a downturn.”

Heater says that SGI’s partnership with the ranchers plays a supportive role in the conservation of the species — which is especially vital throughout these cyclical downturns.

“At SGI, we just focus on the habitat,” says Heater. “But by-and-large, we can make sure that when the numbers drop down — as they tend to do in some of those cyclic periods — that those lows don’t drop as low as they have in the past. If we can keep bumping them up, we continue to win.”

Bryan’s Story: An Unlikely Partnership

Bryan Masini is a fourth-generation, “legacy” cattle rancher on the California-Nevada border who has partnered with the organization for almost a decade. His ranch, Sweetwater, sits at the foot of the Sweetwater Mountains — and in prime grouse territory. The irrigated valleys of his property are dense with the wet meadows that draw in scores of brood-rearing sagehens in the summer months.

“The thing I like about working with SGI is that it’s so user-friendly,” says Masini. But he’s still somewhat skeptical of government interference in private agriculture:

“There’s a lot of politics at play,” he says. “We’re really trying not to list the grouse. A lot of these ranchers around here — their big worries are: ‘What happens to us if business changes?’ ‘What if there’s a drought?’ ‘What if… What if… What if…’ To be very frank, I’ve heard a few horror stories about conservation agencies getting involved (with ranching practices). Way back in the Obama years, a lot of our back-and-forth with the government about potentially listing the bird felt very… adversarial.”

“But in this case,” says Masini, “Senator Harry Reid and a lot of other guys — guys who I may not even be politically in-line with — got together and used the U.S. Department of Agriculture to come up with this alternative solution. And then there was great cooperation between those two political sensitivities — with the ‘Ag’ people in the middle of it, who work for the government. But as I like to say, they really work hand-in-hand with the farmer. They worked really hard to make sure we could still make a living — because we all have to make a living.”

A Decade Of Citizen Conservation

SGI assessors and conservationists have worked with Masini and his staff to tweak the yearly grazing patterns of his cattle, so as to not damage grouse habitat or disrupt their migration patterns:

“It was actually more of a cooperative thing on when I could graze, what my grazing practices are — and then trying to coordinate those things with the science that’s out there on preserving these birds. It’s like the basic principle of, ‘don’t destroy all the grass, don’t (let the cattle) overeat it.’ But there is some leniency. When SGI came in, they took a look at all that, but still gave us some flexibility. What they did was they came out and walked every corner of this ranch. Then they came to us to ‘put sustainability into our existing system,’ yet left us enough room in case we had financial problems and had to change our practices — or otherwise, had to sell.”

In the years since Masini began working with the organization, SGI specialists have helped him fine-tune his grazing practices, as to not disturb the summering birds:

“What we do now is that we won’t run our yearling cattle through our valleys in the summer,” says Masini. “Because if we did, they’d spread out into the grasslands, which is typically where the sagehen tend to bring in their young from the leks. They’ll raise their young in those wet meadows and then move on to those steppe-areas, so we steer clear when that time comes.”

As a result, Masini and his family have conserved more than 4,000 acres of grouse habitat on their ranch throughout their long partnership with SGI.

“This organization has helped to protect this unique symbol of the rangelands,” he says, “While also protecting a uniquely-American way of life.”