What if the key to convincing someone to get vaccinated isn’t facts or statistics—but a story? Stories have a unique ability to connect with our emotions, making complex or intimidating topics feel more relatable and personal. But here’s the twist: not all stories work the same way. Some can backfire, particularly when they try too hard to address doubts or come across as overly persuasive. The power of these stories also depends on who’s listening and how uncertain they feel.

As science communicators, one of our most pressing challenges during and after the COVID-19 pandemic has been addressing vaccine hesitancy. Although facts and statistics about vaccine safety and efficacy are essential, research increasingly shows that storytelling—narratives—can be a powerful tool for influencing attitudes and behaviors. A recent study by Yan Huang published in the journal Science Communication explains how narratives, psychological uncertainty, and message sidedness interact to shape public perceptions of updated COVID-19 vaccines.

Study Methods Overview

In this study, Huang conducted an experiment where 600 participants were exposed to different types of messages about COVID-19 vaccines: one-sided narratives that supported vaccination without addressing concerns, two-sided narratives that acknowledged potential concerns before advocating vaccination, and non-narrative messages that stuck strictly to the facts. Prior to reading these messages, participants were primed to experience vaccine certainty or uncertainty via a short writing exercise.

The study found that when people experienced high levels of uncertainty about COVID-19 vaccines—such as concerns about new variants or vaccine side effects—a simple, emotionally engaging narrative was more persuasive than complex, fact-heavy messages. Specifically, one-sided narratives (those presenting only supportive arguments) were particularly effective under conditions of high uncertainty.

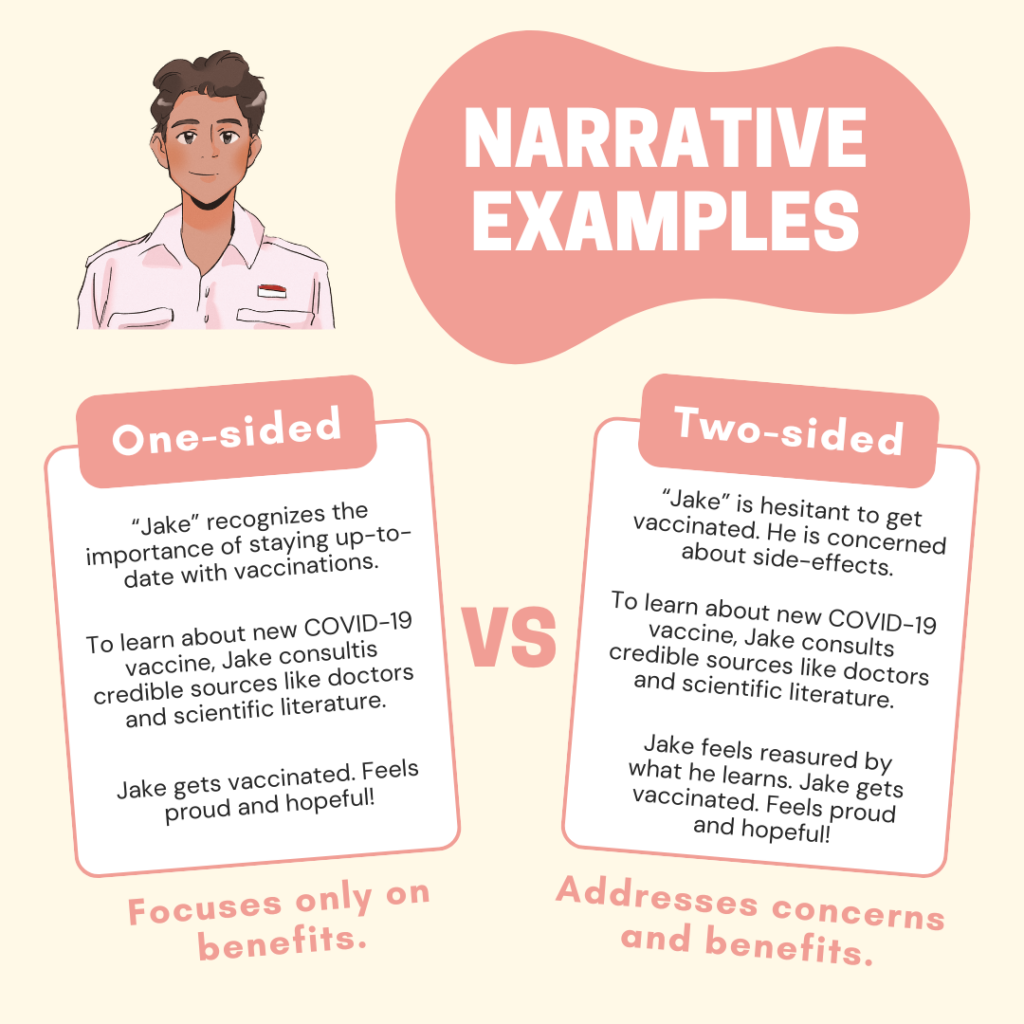

In this study, for example, the researchers told the story of “Jake,” a man who was convinced to get his COVID shot update after reviewing scientific literature, talking to his doctor, and remembering the sense of relief and peace of mind he felt after his first vaccine. This one-sided story resonated emotionally with audiences, reduced counterarguments, and fostered positive attitudes toward vaccination. This makes sense: when faced with ambiguity, humans often rely on emotions rather than logic to make decisions.

Furthermore, the study author found that not all narratives are created equal. The research revealed that adding opposing viewpoints to a narrative—creating a two-sided story—can backfire. In the two-sided narrative, Jake hesitated to get vaccinated, remembering the side-effects he experienced after his first vaccine and uncertainty about his level of natural immunity due to a past COVID-19 infection. Although he reviewed scientific literature and his doctor reassured him, the story’s acknowledgment of doubts triggered critical thinking and counterarguing among the “high uncertainty” participants, reducing its persuasive impact. This suggests that while addressing potential concerns may seem like a way to build credibility, it risks undermining the emotional connection that makes narratives so compelling.

Interestingly, according to the research, the effectiveness of these strategies depends heavily on the audience’s state of mind. Under low uncertainty, where individuals feel more confident in their decision-making, neither one-sided nor two-sided narratives showed clear advantages over non-narrative messages. In such cases, other factors, like prior attitudes or heuristic cues – simple rules that individuals use when making personal decisions– might play a larger role.

What does this mean for science communicators?

First, understanding your audience is key. If you’re targeting individuals who are uncertain or hesitant about vaccines, consider using one-sided narratives that focus on relatable characters and evoke positive emotions. For example, sharing personal stories of individuals benefiting from vaccination can create an emotional bridge that data alone cannot. Second, resist the urge to overload narratives with conflicting information. While transparency is important, too much complexity can dilute the emotional power of a story.

Ultimately, this research emphasizes the importance of tailoring communication strategies to both the audience and context. Stories have a special way of touching our hearts and minds, which makes them a powerful tool for communication — and a tool that must be used responsibly. When it comes to vaccines, facts and figures are important, but they don’t always connect with people on a deeper level. Stories, on the other hand, can make complex ideas feel personal and relatable. By using the emotional power of storytelling, science communicators can create messages that do more than just share information—they can inspire people to take action.

Abdulmalik Adetola is a master’s student in the Media Innovation and Journalism program at UNR and a graduate assistant for the Hitchcock Project. He is a passionate advocate for health literacy and digital communication, dedicated to promoting accurate and accessible health information in the modern age.