Photo caption: WM materials recycling facility manager Mickey Eckman leads a tour of the Reno MRF. Contamination in the form of bubble wrap can be seen behind her.

Across the United States consumers who put plastic materials in their curbside recycling bin are initiating the first step of what could be a cross-country journey that will end with it being turned into, or incorporated into, a new product.

Unfortunately, the recycling process can be complex and opaque and there is little oversight. This does not inspire consumers to recycle or recycle well which is contributing to the buildup of plastic pollution in the environment.

Complexity

The complexity begins with all the different types of plastic. There are seven main resin types, all identified by number.

The most common plastic in daily life is #1 polyethylene terephthalate (PET). This type of plastic is used to make single-use beverage containers and food packagings, like a Coca-Cola bottle in the 7-11 cooler or the branded cup used for an iced latte at Starbucks.

The second most common plastic is #2 high-density polyethylene (HDPE). This rigid version of plastic is used for things like milk jugs and laundry soap containers.

Rounding out the common consumer-facing plastics is #5, polypropylene (PP). It is often used in prescription medicine bottles, yogurt cups, hummus tubs, single-use cutlery, and shampoo.

The next layer of complexity is that recycling programs are mandated by towns and communities, so the types of plastic that can be recycled vary depending on location.

“The problem with recycling in the U.S. is that it came out of waste management and the thing about waste management in the U.S. is that it is a local issue,” said Patricia Moore, president of the Plastic Recycling Corporation of California (PRCC). “Every place has their own dump, transfer station, etc. It is all done locally, so recycling is done the same way.”

In most communities, rigid plastics numbered 1,2, and 5 are generally recyclable. Residents need to check with their waste disposal company to find out exactly what can be recycled in their area. This is further complicated by manufacturers mislabeling their products as recyclable when they are not.

“So many people just have assumptions on what is and isn’t recyclable because we have this local program, but there are all these other factors coming in that confuse people,” said Phoebe Judge, ombudsman and recycling coordinator of WM, formerly known as Waste Management, in Reno. WM is the largest garbage company in the U.S. “So, it is not something that WM has said that makes recycling confusing. It is an individual going to Walmart and seeing a box of plastic bags that say that ‘This is for recycling’, and the consumer thinks, ‘Oh, well, I can use this to put my recyclables in,’ which isn’t the case. So, we are constantly combatting things that manufacturers are saying.”

The confusion leads to contamination and items that could be recycled getting sent to the landfill.

“About 20 percent of everything we get is contamination. Trash, plastic bags, things that are just generally wish-cycled,” said Judge. Wish-cycling is a term that WM uses for items that people feel guilty about throwing away and they “wish” could be recycled.

“We have had people put paint and motor oil in their recycle bin. Once, motor oil contaminated an entire load of recycling that then had to go to the landfill,” said Judge.

To combat wish-cycling and contamination, WM makes a concerted effort to educate its clients.

“We have a process where we are trying to educate and reduce contamination by creating a disincentive. They get two warnings, then three fines, and then they remove the recycling bin,” said Judge.

The Market

The first stop for plastic on its journey to be recycled is a materials recovery facility (MRF). MRFs are where materials that are comingled in a residential recycling bin go to be separated.

The different types of plastic are separated by an optical sorter that is first looking for different shapes and then types of plastic. Hand-sorting is still used by WM’s Reno MRF to separate high-density polyethylene plastics and then further sort them based on color.

Once separated, each type of plastic is baled up and then ready to be sold to reclaimers, where they are converted into clean raw materials to be sold to businesses that will turn them into a new product. In some cases, vertically integrated product manufacturers will do the reclamation process in-house.

Plastic bales have a commodity value, and prices vary as supply and demand for each type of plastic ebbs and flows. It also varies based on the quality of the material that has been baled up, also known as “bale standards.”

The standards for PET bales were set by the Plastic Recycling Corporation of California because they are leaders in plastic recycling efforts. In California, most of the PET comes from the buy-back program because of its container deposit law, also known as a bottle bill. Consumers pay an extra 5 or 10 cents when they purchase any plastic bottles and get that money back when they deposit the bottle at a California buy-back center.

The materials that come from these buy-back centers are usually clean (not mixed with other plastics), and high-quality PET material. This would be a “Grade-A” bale according to PRCC standards and commands a higher price.

Bales that come from residential recycling and are sorted at MRFs are “Grade B” bales because of the higher risk of contamination from other plastics. Bale standards for other plastics are generally set by the Association of Plastic Recyclers, an international trade association representing the plastics recycling industry.

APR publishes design guidelines for plastic materials to try to maximize recyclability and sets bale standards for all recyclable plastics to ensure that plastic buyers are getting exactly what they need.

Prices for these bales also fluctuate as supply and demand change. According to Resource Recycling.com, PET prices have increased from a low of 7.53 cents per pound in September of 2022 to 33.42 cents per pound in March 2023. This type of price fluctuation makes markets difficult to predict for recyclers.

“So, the problem is you’ve got these recyclers who already have to compete with low-cost virgin [plastics], really cheap disposal costs, we don’t have bottle bills, we don’t have EPR (producer responsibility bills), so they don’t get enough supply and they are competing with all these other economic conditions,” said Nina Butler, CEO of Stina, Inc., a company that provides programs and tools designed to facilitate recycling.

Despite these fluctuations and challenges, there are 192 plastic recycling companies in the United States, according to ENF an online directory of recycling companies.

“There is more than enough capacity in California to convert every piece of plastic collected into clean, raw materials that can then be used to make new bottles, packaging, etc.,” said Moore.

But, to build the recycling market across the country there needs to be consistent, and higher quality flows of materials to steady the market and make the economics of getting into the recycling business more appealing.

Misinformation and Unseen Harm

Then there is the misinformation about if and where plastic is being recycled, especially since China stopped taking materials for recycling in 2017. Some of this misinformation comes from the fact that there is no official governmental oversight into the recycling industry.

“Local communities get to decide how much oversight they want. But most communities have handed over all oversight to the trash haulers,” says Moore.

So, all the reporting is done by the trash haulers and the recyclers themselves. It takes independent organizations, like Stina, Inc, to compile those reports and perform voluntary surveys of recycling businesses.

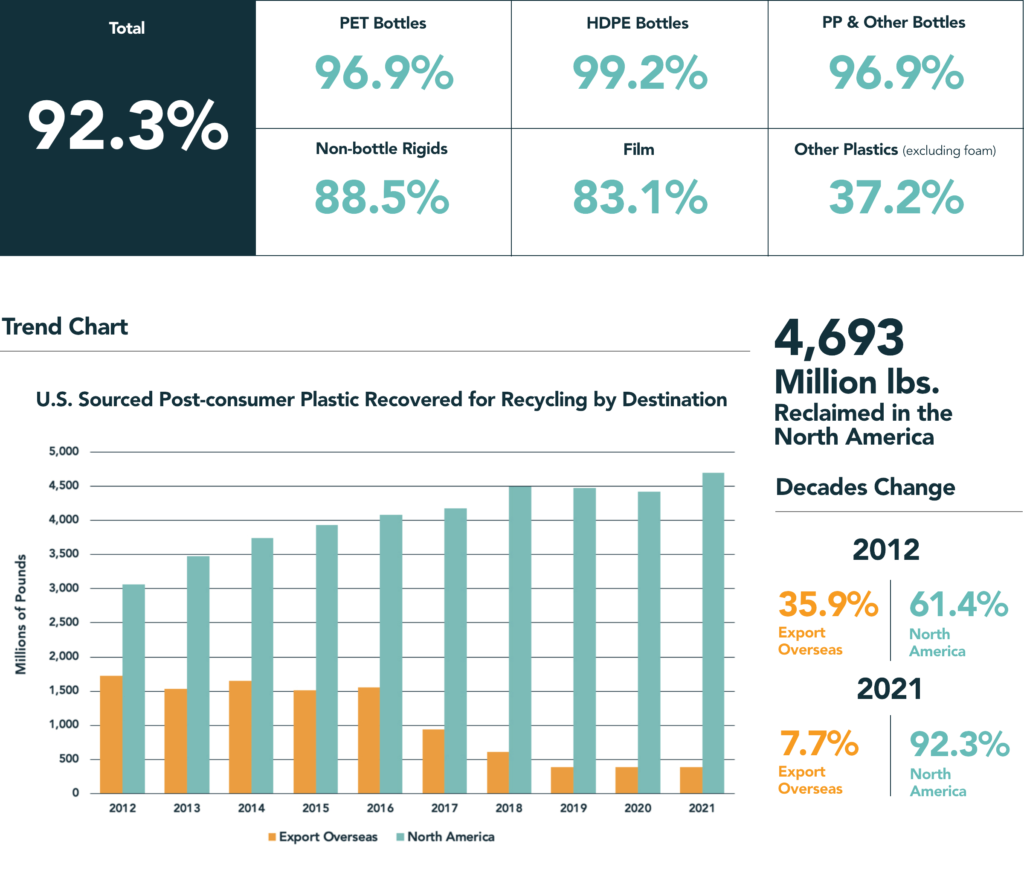

Its 2021 recycling report, released in March of 2023, shows that 92 percent of all plastic collected in the U.S. for recycling is being recycled in North America. This is encouraging to consumers who want to recycle, but our overall recycling rate is still low.

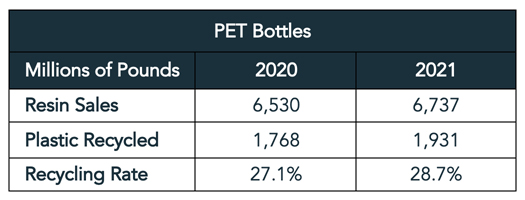

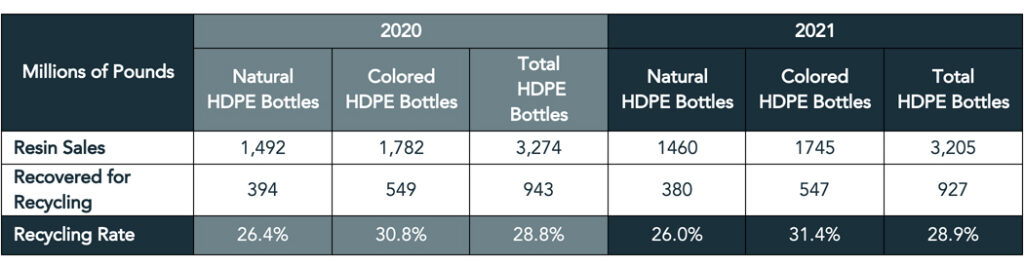

The same report shows that the recycling rate for the two most common plastics PET and HDPE is still hovering around 30 percent. The ultimate goal of recycling is to create a circular economy for plastic, which would mean that no new plastic needs to be produced, but we are a long way off from that.

“We can’t not recycle. We have more human-made material on the planet than all the living biomass,” said Butler.

Butler’s concerns go beyond just the world filling up with plastic waste.

“We are so distracted getting a claim of recyclability, we are not regulating toxins,” she said. “We have to get it out of the environment as fast as possible because it is a ticking time bomb.”

Recent studies have shown that chemicals in plastic are having a harmful effect on the environment and human health. Butler’s concern is that toxins from plastic are going to start impacting the forests and other ecosystems that serve as carbon sinks at the time when we need them the most.

“I volunteer on all these expeditions up in Katmai, Alaska, where no humans currently live,” she said. “The amount of plastic coming into the shoreline from international waters is staggering. In one week, we pulled in 20,000 pounds of plastic off the shores.”

During her work in Alaska, Butler witnessed bears eating plastic and then spreading the contamination through the forests as the plastic passed through their systems.

“We were out watching these bears grazing in this beautiful meadow right under a glacier,” Butler said. “There were over 20 bears mowing this meadow down and it dawned on us that they could be consuming plastic.”

So, they sampled the bear excrement and found it was full of microplastics. This could not only negatively impact the health of the bears, but it could negatively impact the broader ecosystem as the contamination is spread.

“We have to start looking at the impairment factor of plastic and chemicals on ecosystems that sequester carbon and sustain life on earth,” said Butler. “Because we don’t measure any of that we don’t have the true cost of disposal, and we subsidize (the oil and gas industry), and we are stuck in this linear consumption pattern. We are not in a circular consumption pattern, and we never will be until we come to terms with the value of nature.”

Where does your recycling end up?

Recycling is critical to minimize the impacts of plastic pollution, especially since plastic production is projected to increase 30 percent between now and 2050, according to Stastista.

Clarity about where recycled materials ended up might encourage more recycling. According to the report from Stina, Inc., recycled PET plastic can end up in a variety of products. Forty-three percent of recycled PET wound up back as bottles, 35 percent was recycled into polyester fibers, and the remaining PET went into making sheets, films, and strapping.

There is a common misconception that PET plastics can only be recycled a few times before they degrade too much to be useful anymore.

“If you had a closed-loop system with only recycled materials, you could recycle the PET technically 6 times before it would become too yellow,” said Moore. “But, because we are not dealing with closed-loop systems, and new materials are getting mixed in every time, it is not an issue for recyclers at this point.”

The primary end uses for recycled HDPE bottles in 2021 were new bottles (45 percent) and pipe (27 percent), with lawn/garden, automotive applications, construction products, film/sheet, and plastic lumber/decking as other notable end uses. All these materials make it to recyclers and reclaimers who turn it into these new products by a variety of channels.

“We have folks who specialize in brokering the recycled materials, setting up where that material is going to go, and can have relationships with mills that are either going to make it into something new or are going to turn it into a product that can then be used to make a new product,” said Mickey Eckman, manager of WM’s MRF in Reno.

For recyclers who don’t have established contracts with waste haulers, they can connect with material suppliers via the website www.plasticsmarkets.org, which is run by Stina, Inc. The website connects suppliers and buyers of all types of scrap plastic and is intended for use by the recycling industry in North America.

“If you generate something with quality bale specifications, chances are that you will be able to sell it to someone and they will be able to convert it into a new product,” said Moore.

Stina, Inc. also runs www.recycledproductsdirectory.org which lets consumers find products that are made of recycled materials to help drive demand. The site lists dozens of companies and products that use recycled materials.

Even though the recycling system in the U.S. is fragmented, consumers should feel confident that their plastic recycling is actually being recycled. Hopefully, this confidence will drive more recycling and less plastic waste in the environment.

Cara Hollis recently graduated from UNR at Lake Tahoe with a major in sustainability and journalism. She wrote this story for Journalism 493, Independent Study, with Professor Jim Scripps.