In the cool months of spring, clusters of yellow flowers bloom in the valleys of Northern Nevada. It’s a rare treat to spot this special plant – the Carson Valley monkeyflower (Erythranthe carsonensis)— which, until a couple of years ago, scientists did not know existed.

Naomi Fraga, director of conservation programs at the California Botanic Garden, discovered it in 2012 while studying other monkeyflowers.

“It was flying under the radar,” said Fraga, who often works with conservationists in Nevada to protect rare plants. “Nobody really knew about it, but it was growing in the Carson City area in the valleys there right where there’s a lot of commercial and housing development.”

The Carson Valley monkeyflower is native to the Carson Valley region of Nevada. However, unless serious conservation actions are taken, Nevadans may not encounter this plant for much longer.

Growing population, growing threat

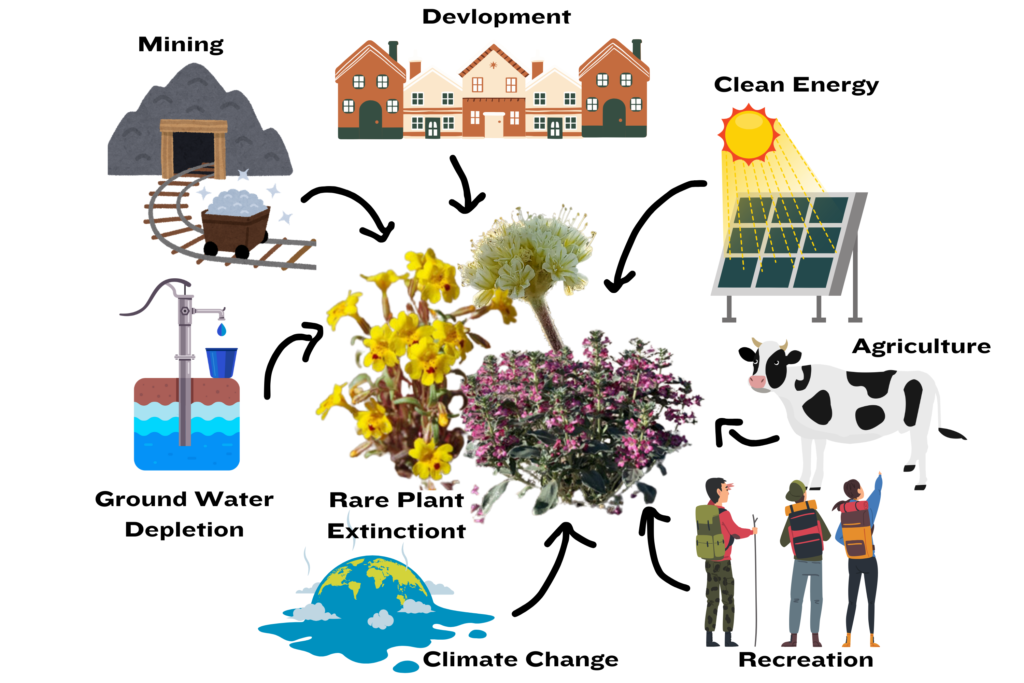

Nevada is experiencing a population boom, with almost half a million people flocking to the state in the last decade. With new people comes new development—and a lot of it. The state has seen record levels of housing and industrial development, but this boom puts some of Nevada’s rarest species at risk of extinction.

Nevada fosters a diversity of plant life. Over 2,800 different plant species are found in the state, 352 of which are rare. A plant species is classified as rare when it has small populations or is found in very specific areas. However, this rarity puts them at a heightened risk of extinction.

“We’ve always had plants that are naturally rare, but I would say those rare plants are becoming increasingly imperiled or endangered due to different actions humans are taking,” says Fraga.

While several plants are protected under the Endangered Species Act in Nevada, protection does not extend to private land. This makes plants already found in such a limited range particularly susceptible to development projects.

“When your habitat is being totally mowed over or modified in some way, usually, rare plants can’t deal with that,” says Fraga.

Monkeyflower under pressure

According to a 2018 report from the Nevada Division of Natural Heritage, 42% of the Carson Valley monkeyflower habitat has already been lost due to residential and industrial sprawl. In January of this year, the Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the Carson Valley monkeyflower under the Endangered Species Act.

Patrick Donnelly, Nevada state director for the Center for Biological Diversity, recently witnessed the removal of some of these plants firsthand.

“Naomi [Fraga] and I were surveying the Carson Valley monkeyflower last year, and we watched them bulldozing the habitat,” said Donnelly. “Saw it with our own eyes. There’s a bulldozer. There’s a monkeyflower under the bulldozer.”

The flower prefers to grow on sandy flats, land that’s often sought-after real estate for housing developments. While only an estimated 18% of the Carson Valley monkeyflower grows on private land, when a plant is found in so few places to begin with, removing any habitat can have a big impact.

Plans are underway to build a multi-unit housing development in Gardnerville Ranchos, removing a large portion of private land where larger populations of the plant thrive.

“If all of the private land development possibilities came to fruition, I would be worried about the continued existence of the Caron Valley monkeyflower,” says Jamey McClinton, administrator of the Nevada Division of Natural Heritage.

A statewide challenge

Development isn’t just a problem in the Carson City region; it’s affecting rare plants across the state. The white-margined penstemon (Penstemon albomarginatus), a rare species that grows in Las Vegas, is also facing significant threats from development. Proposed land bills in Clark County, Nevada, would breach the territory of the white-margined penstemon, putting it at risk for extinction.

“The proposal would sell off 40,000 acres of public land South of Las Vegas…much of that land is habitat of the white-margined penstemon,” says Donnelly.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently announced that after an initial review, the flower may qualify for protection under the Endangered Species Act.

While the Endangered Species Act won’t protect plants currently on private land, it has been successful in preventing many from becoming extinct. According to the World Wildlife Fund, 99% of species protected by the list have avoided extinction.

“Even though the Endangered Species Act doesn’t actually require you to prevent extinction, it sure makes it a lot harder,” says McClinton.

However, according to a 2022 study, Nevada’s rare plants face many threats, including proposed solar, geothermal, and lithium mines.

Fraga is now gearing up to survey Sodaville milkvetch (Astragalus lentiginosus var. sesquimetralis), a rare plant which occurs in small populations across Nevada and California. According to Fraga, the plants reside in areas proposed for new clean energy projects.

“We share the planet with many organisms, and that is part of what makes the earth a very special place. I think it would be a very sad and lonely planet if it were just us,” says Fraga.

Elizabeth Walsh is a Ph.D. candidate in the Biochemistry Department at UNR, where she studies mosquito biology with the Rueckert Lab. She wrote this story for the Hitchcock Project’s science reporting course during Spring 2024.