Nevada is a big player in renewable energy. But while it ranks among the top five states for both solar and geothermal energy production, it lags well behind in wind energy production, where it falls 33rd.

This fact surprised UNR Reynolds School of Journalism graduate student Benjamin Payne, who last year moved to Reno from his native Illinois. Whereas that state boasts more than 50 wind farms, Nevada has only one. He decided to look into this gap, and figure out why wind makes up such a small sliver of Nevada’s energy mix.

Shouldn’t the Silver State have more wind farms than the Prairie State? After all, Nevada is plenty spacious, with about twice the land area as Illinois.

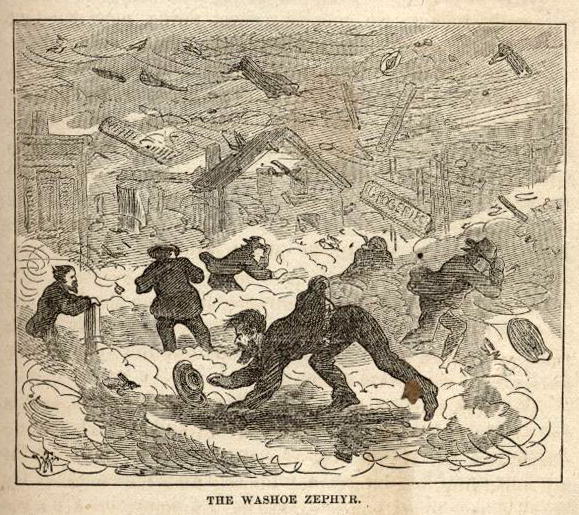

On top of that, it can get quite windy in Washoe County and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Mark Twain even wrote about it in his book “Roughing It”:

But seriously a Washoe wind is by no means a trifling matter. It blows flimsy houses down, lifts shingle roofs occasionally, rolls up tin ones like sheet music, now and then blows a stage coach over and spills the passengers; and tradition says the reason there are so many bald people there, is, that the wind blows the hair off their heads while they are looking skyward after their hats.

It turns out that’s part of the problem.

“The winds tend to be gusty and not consistent,” said renewable energy consultant Rebecca Wagner, who directed the Nevada Governor’s Office of Energy from 2005 to 2006. “So we’ll get really high winds, but not good, solid, sustainable winds that you would see in the Midwest through the [Great] Plains.”

Strong gusts on a wind farm might seem ideal — like a clear, sunny sky on a solar farm — but they’re anything but. A gust can overwhelm a turbine to the point of tearing apart its rotors. That’s why turbines are built with brakes to protect them. A gust of 35 to 40 miles per hour is enough to grind the turbine to a halt. Sure, the brakes prevent damage, but they also prevent power from being generated.

When it comes to wind, too much of a good thing is a bad thing.

After Wagner directed the Office of Energy, she served as a commissioner on the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada, where it was her job to review proposals from energy companies that wanted to set up shop in the state. Although lots of proposals for solar plants and geothermal plants came to her desk, the same could not be said for wind.

“We just weren’t getting wind projects proposed,” Wagner said. “And if they were proposed, they weren’t cost competitive with the other resources.”

For example, take solar. Sunlight is pretty much everywhere. Yes, some areas are better and brighter than others for setting up a solar farm. But wind? You have to go far and wide to find those good, consistent winds that Wagner talked about.

“They’re in relatively isolated spots,” said Darrell Pepper, a mechanical engineering professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He co-authored a 2007 study that analyzed data from several meteorological towers across the state, each one about 15 stories high — basically, souped-up weather vanes to detect windy hot spots.

He did find some hot spots, but they “were pretty difficult or almost impossible to try to get to,” Pepper said. “What you also have to factor in, of course, is the cost of installation and the fact that you need to get some pretty heavy equipment in there to actually set up the turbines. It’s really not a question of the technology. It’s a question of the economics.”

Jason Geddes, who oversees renewable energy projects for the Washoe County School District, agrees: “With the basin and mountain terrain, we just get a lot of wind gusts that make very few sites in Nevada viable for large commercial wind turbines.”

Geddes used to work for the City of Reno, where he wanted to try something out: if Nevada isn’t a good fit for large wind farms, went the thinking, perhaps smaller turbines could work — and maybe even slash the city’s energy bill.

So, he oversaw a pilot program that installed eight turbines on different government properties, including Reno City Hall. The two on that property disappointed him.

“The ones on City Hall, they were rated at 1.5 [kilowatts] by the manufacturer,” Geddes said. “And when we got them into production, they were closer to 300 watts.”

In other words: one-fifth the power of what was advertised by the manufacturer.

“Despite the claims that they work in an urban environment, they don’t,” Geddes said.

That’s because when buildings are in close proximity, as they are in the city, they form a sort of barricade that disrupts the wind’s natural patterns. Either the wind blows too hard (in the case of high-rises and skyscrapers) or too soft (in the case of high-density residential neighborhoods).

So, urban settings are mostly a no-go. But in suburban settings, it’s a different story. Outside the city, where buildings are fewer and farther between, the winds have room to roam.

This was the case in Reno’s more rural North Valleys, where Geddes set up three turbines at the Reno/Stead Water Reclamation Facility.

“They actually worked very well,” Geddes said.

They’re working well not just for municipalities in suburban settings, but also for some suburban homeowners, like Marsha Cardinal. The biologist lives just outside Reno’s North Valleys, where her flat desert homestead is surrounded by a sea of sagebrush. Rising high into the sky above Cardinal’s backyard is her very own turbine.

She’s proud to show it off and walk through its installation: “You mount everything on the ground,” said Cardinal, pointing to the concrete and rebar foundation required by Washoe County.

“And then we had a crane. It lifted it up, lifted up the nacelle,” said Cardinal, referring to the enclosure that houses the turbine’s electrical components.

If the words “backyard wind turbine” make you think of a mini-golf course, think again: Cardinal’s stands 34 feet tall, from the base to the top of the main shaft, which holds three rotor blades.

With its towering height and scythe-shaped rotor blades, Cardinal’s turbine looks much like the kind you’d find at a big commercial wind farm, just at a smaller scale.

Because it’s smaller, it generates far less power, but still enough to reduce the carbon footprint of Cardinal and her husband, which is why she bought it in the first place — to help the environment. An added bonus: it slashes $30 from their monthly electricity bill.

“The wind is free,” Cardinal said. “This turbine will turn with as little as five miles-an-hour wind, so that’s an afternoon breeze.”

The wind may be free, but of course, the turbine isn’t: this one costs $6,000. That’s on top of another $6,000 to lay the foundation, plus a few hundred more for permitting fees.

The turbine has been up and running for about 10 years, though, so many of those costs have been recouped through energy savings.

“It’s almost paid off!” Cardinal said. When asked what she means by ‘almost’: “It’s probably another 10 or 15 years. We’ll probably be dead by then,” she said with a laugh.

Slowly but surely, it is paying off for Cardinal. And that’s the thing: there’s a big difference between a homeowner who just hopes her turbine pays for itself in the long term and a power company that wants its turbines to turn a profit in the short term.

The economics of wind power just haven’t played out at the commercial scale, said Wagner, who points to the state’s strong solar and geothermal development.

“It’d be nice to be able to balance that out with a good strong wind portfolio,” Wagner said. “But right now, I just don’t see that investment in Nevada.”

Wagner isn’t ruling out future technological advancements, which she said could possibly harness Nevada’s strong gusts. But at least for now, the economic windfall isn’t there.

This story also aired on KUNR Public Radio.

In the audio version of the story, the excerpt of “Roughing It” was read by KUNR reporter Paul Boger.