What will our lives be like after the COVID-19 pandemic has come to an end? As we navigate the uncertainty of our present situation, the uncertainty of what the future may hold weighs just as heavy. Will this pandemic change our lives forever? Will we be living in a “new normal” indefinitely? Is there any hope of returning to life as we knew it pre-COVID? These questions are speculative, but clues scattered throughout history and lessons from our past could help us answer them.

As a society, we may be more prepared to handle the potential changes ahead of us than we realize. We have been adapting to “new normals” all our lives without really realizing it, says Dr. Markus Kemmelmeier, a social psychologist at the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR). Kemmelmeier is an expert on social and cultural psychology and the Director of UNR’s Interdisciplinary Social Psychology PhD program.

What is “normal”?

If the question is whether or not we will return to ‘normal’ after the risks associated with COVID-19 have been mitigated, Kemmelmeier says, “it depends, what do you mean by normal? We are already in a type of ‘new normal’ simply because we’ve gotten used to this for now.”

We have become accustomed to wearing masks, practicing social distancing, checking the news for daily death counts, and many other societal changes that were not ‘normal’ to us six months ago.

While we may be well-equipped to adapt to change, Kemmelmeier reminds us that “there is a lot of evidence to suggest that people have a very short memory.” Perhaps the best historical example of this, and the closest comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic that we can draw from, is the Great Flu of 1918.

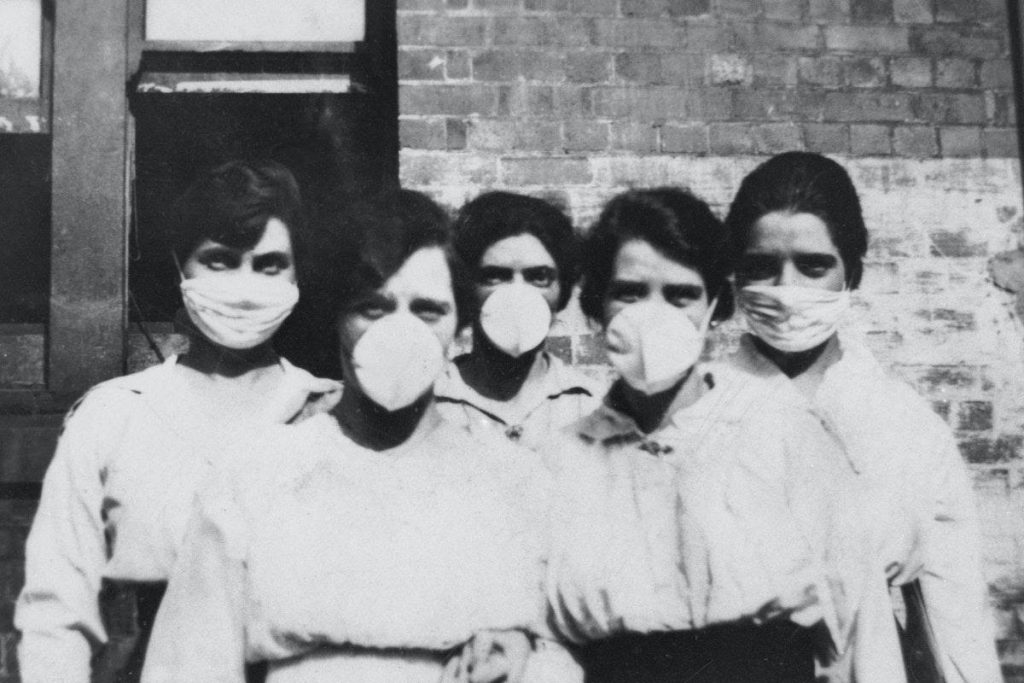

Doctor Martha Hildreth, historian and Emeritus Professor at UNR, says that while a lot of good actions were taken during the Great Flu pandemic, no real change resulted. The 1918 pandemic brought about many of the same actions we see being taken today: masks were worn in public, theatres were closed, and churches were made to hold services outdoors– just to name a few.

However, no historical evidence or literature on that time period points to any long-lasting changes resulting from this pandemic.

The Great Flu killed an estimated 40 million people worldwide, but history points to a reality in which the rest of society moved on without lasting repercussions. As Hildreth reminds us, at the time of the Great Flu pandemic the country was recovering from World War I of 1914-1918. The fact that the trauma and hardships of the war were top of mind may contribute to the lack of focus on the Great Flu.

It may be surprising that the pandemic left no long-lasting impacts on societal culture. Kemmelmeier echoes this observation, stating, “the 1918 pandemic killed many more people than died on the battlefield in the war, and in spite of this, people didn’t really want to think or report on that.”

However, this does not mean that we will see no real change as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Infectious disease epidemics do have huge potential for changing cultures,” Kemmelmeier says.

Hildreth’s expertise on the history of medicine provides us with several examples of this happening in the past. The Black Death of the 14th Century resulted in the creation of quarantine systems that remained in place for subsequent outbreaks of disease. The 18th and 19th century tuberculosis outbreaks lead to the creation of Public Health Authorities. Smallpox led to the start of vaccines in the western world, as George Washington required his troops to be vaccinated during the outbreak of the 1700’s. The AIDS epidemic changed sex habits in our society. Perhaps the pandemic of 2020 will lead to change as well.

Long-lasting Impacts

Going forward, what type of long-lasting impacts can we expect the COVID-19 pandemic to leave on the modern world? Because of our short memory and ability to adapt to hazards, change is not likely to happen unless it is carried forward by institutions.

“We were already adjusted to a level of hazard. The flu kills roughly 60,000 each year. But, if we aren’t directly affected, we aren’t exactly surprised,” says Kemmelmeier.

This idea that behavioral changes don’t last but institutional changes do is supported by the types of historical changes Hildreth pointed to; public health departments being created, new quarantine systems being put in place, and vaccines being developed. According to Kemmelmeier, these types of changes may result from COVID-19, but behavioral norms are not likely to change.

In other words, will we all stop hugging each other and stop shaking hands after this pandemic? Kemmelmeier says, “Probably not. That’s not likely. These things are so rooted in our traditions; that probably won’t change unless you have a generation of kids growing up in a culture without it. These greeting rituals are institutions in themselves, they’re hard to change.”

Hildreth has a similar take on this scenario, stating that the places that were the hardest-hit, such as Italy, have a greater potential to see cultural changes than we do here in the United States. She says that perhaps, due to the gravity of the pandemic in Italy and considering their more intimate culture, people there will re-think traditions such as kissing on both cheeks as a greeting. However, the American handshake will probably not go away.

Will we continue to wear masks in public once the threat of the virus is gone? Again, Kemmelmeier says this is unlikely; “Wearing a mask reminds us of what is happening. It is a signal to us that there is a virus and this is what we have to do. We see daily case totals on the news and we are told to wear a mask. When we no longer have these signals, change is unlikely.” Hildreth says that because of the unlikelihood that our behaviors will change, a vaccine and advancements in treatment are our best hopes.

The type of changes that are more likely to stick around are things like the new business practices we have adapted to in this time. Kemmelmeier says there is great potential for new types of business to emerge from the pandemic, and that the use of Zoom for business meetings is an example of change that may make companies rethink the way they conduct business going forward. However, this is also rooted in whether or not institutions continue to carry these new ‘norms’ forward.

Perhaps companies will cut travel budgets and opt for Zoom meetings more often; this would be an institutional change. If UNR chooses to continue paying for a university-wide Zoom license, something that has been necessary during the pandemic, this is an institutional change that we will continue to adopt as normal behavior. If UNR does not choose to make Zoom a part of the University’s budget going forward, this will no longer be ‘normal’ to us.

After all, “How do things become normal? Well, by us doing them,” says Kemmelmeier; “hopefully, people at least continue thinking twice about whether or not someone has washed their hands.”

We may not have a crystal ball, but we look to our past as a clue– and perhaps a warning– as to what life after COVID-19 may look like. While the potential for change is very real, so is the potential to stay the same.

We do know that returning to a life much the same as the life we knew pre-COVID is very possible. Why? As Kemmelmeier states, “Because that’s what we’ve done every other time.”