Red abalone (Haliotis rufescens) sense their environment using an epipodium – a foot-like organ covered in tiny tentacles. Similar to human eyes and hands, abalone use their tentacles to sense the environment, tell if there are predators around, and attach to the rocky kelp habitat of the California coastline. Like a large marine snail, their shell is of such beauty that they are coveted all over the world.

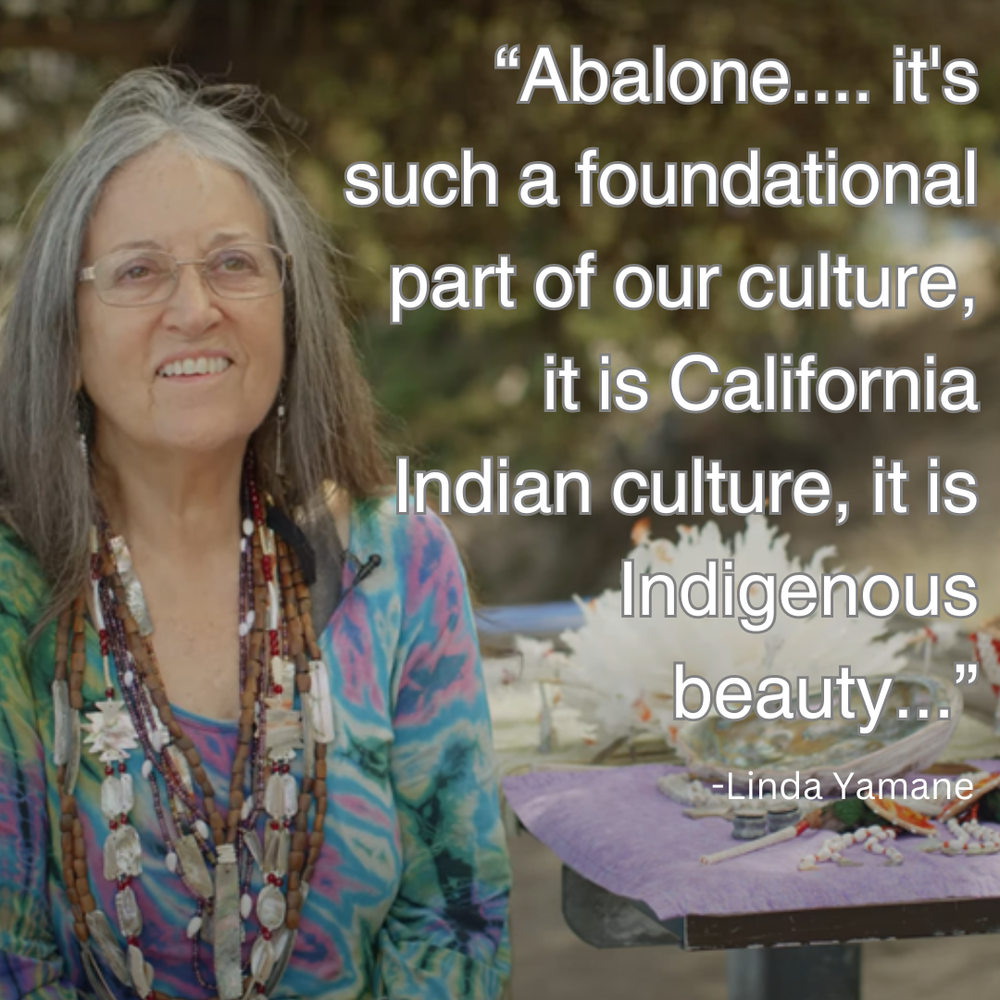

Abalone harvesting has a long history in California, where Indigenous peoples have utilized the shells and meat of abalone for many thousands of years. Commercial harvest was initiated by Chinese Americans fishing from skiffs during the 1850s, an industry that transitioned to divers during the 1900s as conditions and abalone populations shifted. Since 2018, recreational abalone diving in California has been closed due to climate change and population decline. This decision has impacted the species as well as many communities, including Indigenous cultures that have not been able to engage in traditional practices that involve the red abalone. The story of red abalone is a story of many protagonists.

This is what the Ph.D. student of Anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno, Alexandria M. Firenzi, wants to portray with her project, “Beyond the Shell:” that the story involves many characters, and that collaboration is key to both creating better stories and rebuilding and revitalizing communities.

The Beyond the Shell Project consists of several elements: a documentary about the red abalone, a cartoon series called “Rufus the Rufescens“, a social media presence, and a shell donation program called “The Abalone Collective.” This project is not part of Firenzi’s doctoral research, but rather something she does because she, as a scientist, understands the importance of scientific and cultural outreach.

Earlier this year, Firenzi and her team held a documentary screening and panel discussion about the “Beyond the Shell” project at UNR. Afterward, the Hitchcock Project met with Firenzi to learn more about her work, her goals, and her future dreams.

HP: Let’s talk about Beyond the Shell. How did you come up with the project idea?

Firenzi: I was in undergrad during COVID just looking for a research project to partake in and decided it could be something separate from my actual research interest, which at the time was forensics. It could be more creative. So, I talked to my professor about how I used to go red abalone diving and how I missed it and was probably not the only one missing it. [This project] was originally going to be a book, but I thought that it was not very accessible. We decided to turn it into a film, and I worked with the Advanced Laboratory of Visual Anthropology at Chico State.

HP: What is the film about?

Firenzi: The point of the film is to look beyond the shell, beyond just the abalone. It is to look at the communities, the biodiversity, everything that’s affected by this species. Because it’s such a beautiful shell, everyone just focuses on the abalone, but with the abalone there are so many other things: there’s kelp forests, sunflower sea stars, urchins, Indigenous groups all along the coastline of California, Japanese Americans, Chinese Americans, many people who have engaged with this species over time. I wanted to look at those communities and how they were affected by the season closure in 2018.

HP: Let’s talk about that season closure for red abalone. What happened?

Firenzi: It started with a few things. There was a marine heat wave called The Blob that happened in 2015-2016 and that coincided with one of the largest El Niño events on record. The two of them together kind of just spiked the sea surface temperature significantly. The red abalone, when it’s in warmer waters, experiences something called withering foot syndrome. It needs to be able to grab onto the rocks, but when it has withering foot syndrome, that muscle becomes weak, so they cannot attach onto rocks to keep away from predators.

Then, on top of that, the sunflower sea stars experience something called sea star wasting disease because of the temperatures, and their population went down to almost extinction, very critically endangered. The fact that that sunflower sea star disappeared meant that the urchin population was no longer being kept in check. They started eating all the kelp, the abalones’ food. It is a two-part where they already were diseased, but then on top of that, their collapse meant that their food source went down significantly, so they were also starving. So, disease and starvation were a big thing, but also fishers and poachers.

HP: You mentioned the idea started as a book, but it ended up being a documentary with a website and other forms of visualizations, such as comics. I am curious to know how you went from engaging in scientific research to science communication?

Firenzi: I think it’s partly for my sanity, because I really like artistic things. So, even though I’m in a hard science with the geochemistry side of my research, I think art is a good outlet for expression. I also feel like cartoons are a really good way to communicate with kids, so I created a cartoon called “Rufus the Rufescens,” because the scientific name for the red abalone is Haliotis rufescens. It is about Rufus, a red abalone who is learning about the environment and cultures around him. In that process, I figured dealing with one piece of information per week was digestible, on topics such as how large the abalone get, how long do they live, why is that diver coming down with the little bracket thing to measure the little abalone? What is it doing?

Also, social media appears in my mind to be a place where a lot of people go for random bits of quick information like that. So, it’s a good way to just kind of get people invested in the species and the environment. Many scientists focus on research and on ‘what can we do?’ But they forget that most of the population isn’t thinking about this science daily. They forget that the rest of society does not think about that daily. So, I figure it’s a way to get people invested in the species and their survival, because that’s what motivates funding, whether these research projects are acted on.

HP: What are other ways in which your project is going “beyond”?

Firenzi: We’re also doing something called The Abalone Collective. I am forming an advisory board with a few women from the film that are Indigenous artists and with Indigenous representatives from throughout the state. At the end of the film, we have a statement about an email for questions and donations for use in Indigenous art, such as red abalone donations. With the advisory board we are looking to determine where those donations are going, but also to form a way of communication between the donor and the donee; we’re bridging communities and their conversations.

HP: Your project website mentions the “two-eyed seeing approach.” What is the two-eyed seeing approach and why was it important for you?

Firenzi: The two-eyed seeing approach is not anything new. If you’ve read Jessica Hernandez’s book, Fresh Banana Leaves, it talks about it. It is the idea that from one eye you can see something from one perspective, and from the other, you can see it from another, and that they don’t have to conflict with each other. For example, Western science and Indigenous knowledge, traditional ecological knowledge, TEK. I like to use this approach because as much as I am a STEM science girl, I do think that there is a cultural element to things, there is a different way of seeing things, there’s multiple ontologies.

I think it’s important, when you’re engaging with a group, to adopt their philosophy and their ontology, their way of seeing something because it might enlighten your perspective. If you go in with just a science mindset, then you’re going to be blinded to a lot of different things. I think a really big thing that ecologists should do is talk to local Indigenous groups and ask them: is there something we’re missing in this region for kelp restoration? Is there something we could be doing as scientists to better reconstruct the environment in this area? I think that’s my main hope for having that philosophy in the project.

HP: How do you think you did? How was that process?

Firenzi: It’s something that I think a lot of environmental scientists and ecologists are starting to employ. It’s something that people aren’t turning their noses up at as they would have 10 years ago, when saying “oh, science isn’t good enough, you also need to employ traditional perspectives,’ might not have been well received. But now, I think people such as Jessica Hernandez, who already are publishing popular books that talk about it, are helping with the social adoption of that philosophy. So, it’s been going well.

HP: Your project makes three promises: to promote the “two-eyed seeing” (Etuaptmumk) approach, to rebuild and revitalize communities affected by the decline of intertidal ecosystem health, and to always make the information accessible. What are the steps you are taking to keep those promises?

Firenzi: I think that my focus is communication. There’s a lot that can be done to rebuild these communities in an on-the-ground way, like going in and actively helping on reef check surveys to try and help the local oceanic population do better and therefore the coastal human population will do better. Since I don’t live on the coast, the approach I am taking is helping people rebuild communication, because I think that if we’re hoping to restore any of these environments there needs to be less fragmentation in the way that people see other cultural groups. If we all take that two-eyed seeing approach and work together and communicate our ideas to each other, that will help to rebuild those communities.

For example, with the Abalone Collective, it’s not just about donating abalone, it’s about building those bridges of communication between the donor and the donee, the Indigenous artist and the sport diver that has boxes of abalone in their garage. I think something as simple as that is helping to rebuild socially because there’s more communication between cultures, but also environmentally because they can share scientific and traditional knowledge.

HP: You had panel discussions and film screenings with time for questions for you and the other groups involved in the film. Why was that?

Firenzi: A big part of the project was being collaborative. A lot of documentaries go in, interview the person, and then leave and produce the video and say, “Here’s the video.” But I didn’t want to take that approach because I understand how scary it can be to sit in front of a camera and just tell your story and have someone go and edit it how they want to without you knowing what’s going on. So, we tried to be extra collaborative. Before interviews, I tried to communicate with the person months in advance when possible, and then after the interview, I let them see their footage and give me their input if they didn’t want anything in there. It was important to also let them point out stuff that really is meaningful to them, because it helps you to pull out important parts of the story that you might not have seen before as just as an external viewer. Finally, once we got to the final product, I did a show for all the people I interviewed that wanted to participate and they were able to share their opinions. In fact, that’s how we came up with the land statement. I originally didn’t have a land acknowledgement there. So, you get a better story in the end when you’re working collaboratively.

HP: How have the audience responses been? Are they as you expected?

Firenzi: They’ve been a lot more positive than I thought, especially coming from the Indigenous community. I was a little bit concerned about having sport divers in the film alongside Indigenous groups. The film was originally intended to include a lot more cultural groups; like the Japanese American Citizens League, which I interviewed, but it didn’t make sense in the storyline, so we removed them and I’m hoping to do something else in the future with their storyline. But it has been well received.

HP: What is next for you?

Firenzi: We’re working on the Abalone Collective and I would also love to do a children’s book at some point. As far as my actual plan for my career is concerned, my next goal is to work for an organization like NOAA or NatGeo, where it’s science communication-based. Even though I’m doing a degree in anthropology, I think that I could easily go into one of those fields because my research is very environmentally based. Oftentimes, environmental scientists don’t necessarily think about the local communities that are being affected by these problems. They just think about the species that they’re working with and that’s it. And I think that is not a reasonable approach in modern times. I’ll be able to bring a more humanistic approach to science.

More information on “Beyond the Shell”

https://www.thebeyondtheshellproject.com

Vanesa de la Cruz Pavas, M.A., is a reporter and science communication specialist for the Hitchcock Project. She is a graduate of the Reynolds School of Journalism’s class of 2023.