Four Dams, Three Women, One River

Reynolds School of Journalism alum Brooke Hess (a science writer and kayaker) has just begun a more than 1,000-mile river journey. Brooke and two other women will travel by kayak, raft, packraft, and skis, the length of the Salmon River from it’s source all the way to the sea.

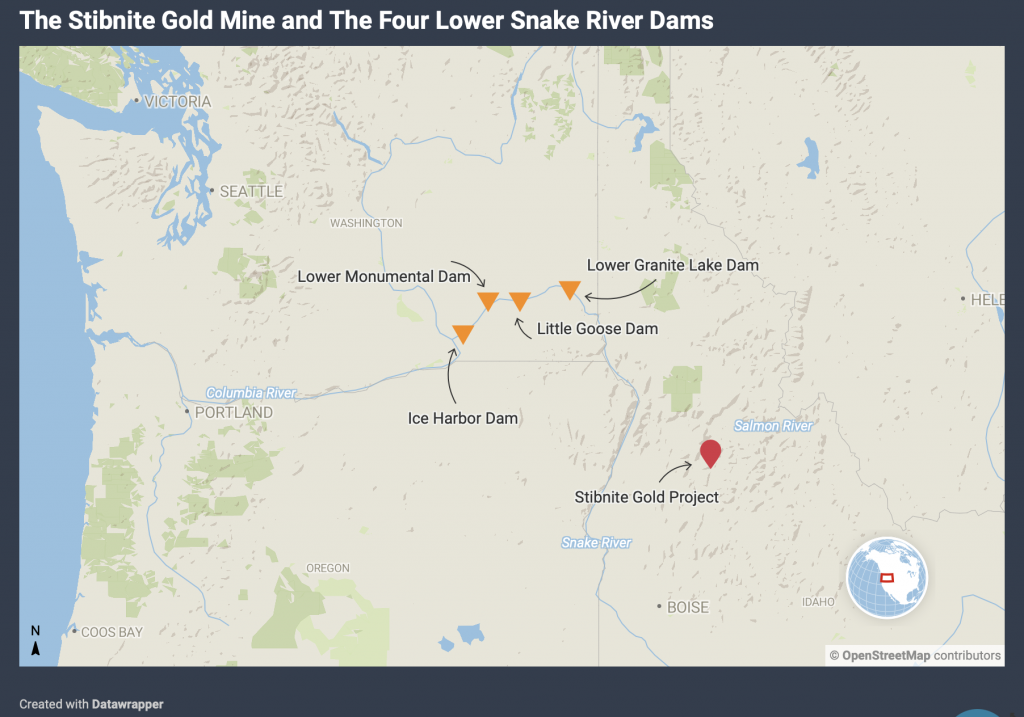

Their goal: to advocate for the removal of the four Lower Snake River Dams in an effort to save the rapidly dwindling Snake River Basin salmon populations from extinction.

Since the four dams were installed in the 1960s, there has been a precipitous decline in salmon populations, as well as other fish.

Salmon in Peril

Snake River Basin Chinook salmon and sockeye salmon are both anadromous fish species, meaning they hatch in the cold freshwater streams of Idaho, migrate to the saltwater of the Pacific Ocean where they spend the majority of their lives, then travel back to the freshwater streams in Idaho three to five years later to spawn (reproduce). Historically, both species have returned to spawn in Idaho in mass numbers each year, but recent population declines have both species fighting against extinction.

Scientists point to the four dams on the Lower Snake River as the culprits causing the declines in salmon populations. Conservationists are urging politicians to breach the dams, pointing out that it is the only way to save the Snake River Basin salmon populations from extinction.

To read Brooke’s article on the Snake River Basin salmon populations, the threats posed to them, and the proposed solution, click here. To follow the three women on their river journey, visit https://salmonsourcetosea.com.