As the bright casino lights dip behind the hills in my review mirror, the sleepy town of Lockwood and bland factories zip by, racing the Truckee River down below. Traveling east from Reno along I-80, fast food wrappers, plastic bottles, and cigarettes leave a trail of breadcrumbs as the life of the city gives way to the desert mountains.

After miles of driving, in the distance, a small but looming tower of pipes and chambers lets me know I’ve made it to Fulcrum Bioenergy’s Sierra BioFuels Plant. Against the cloudy sky, the plant’s glittering lights radiate an exciting energy. Every year, millions of tons of trash are brought to landfills where they await their fate: to be burned or buried. But here, trash is given a new life as renewable energy.

At Fulcrum Bioenergy, one person’s trash is another person’s transportation fuel. Since last December, the Sierra BioFuels Plant has focused on how to convert trash into sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), an alternative to traditional petroleum-based jet fuels. The plant has deemed itself the first of its kind for successfully producing renewable aviation fuel that is then sold to commercial airlines like United. It also addresses two climate concerns: reducing carbon emissions and reducing waste sent to landfills.

Despite these goals, many wonder if it’s too good to be true. In Indiana, a similar project by Fulcrum Bioenergy was met with resistance due to questions related to air pollution, environmental justice, and the use of plastic in its feedstock, according to Inside Climate News.

Trash for Transportation

Across the country, landfills are quickly reaching their limits. As much as we try to recycle or compost our waste, the trash of our past haunts us. In April, the United States Environmental Protection Agency published the latest report on food waste for 2019. That year, 66.2 million tons of food were thrown away, with 66 percent sent to landfills.

At the Sierra BioFuels Plant, heaping piles of trash are a gold mine for carbon materials that can be turned into fuel. Cardboard, plastics, ceramics, and food waste are just a few examples of carbon-intensive solids that can be turned into fuel.

“Before, waste was never seen as a resource. It was more of a nuisance – ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ But with Fulcrum, waste is now being seen as a resource with value,” said Ivan Valera, operations manager of the Sierra BioFuels Plant.

The waste-to-energy process

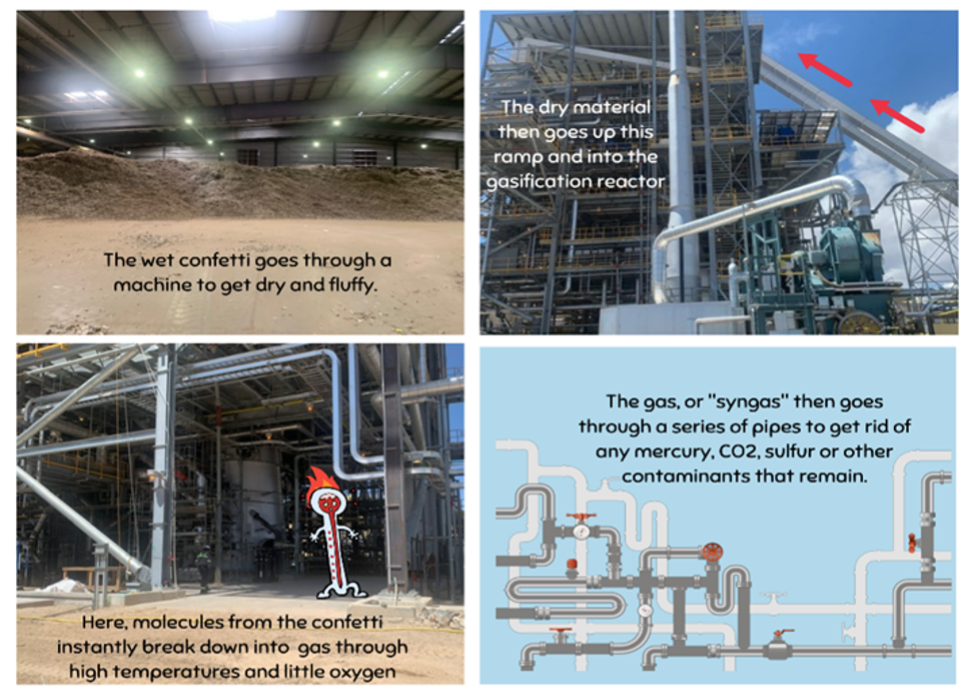

For a closer look at how Fulcrum’s waste-to-energy process works, Valera gave me a brief tour of the biofuels plant. Driving us along the dirt pathway, he pointed to a dimly lit warehouse filled with what looked like the remnants of the blandest birthday party I’d ever seen. Inside, piles of confetti-like material formed their own peaks and valleys. While the confetti-type material might not brighten up a company party, it’s the life of the party for the trash-to-fuel process.

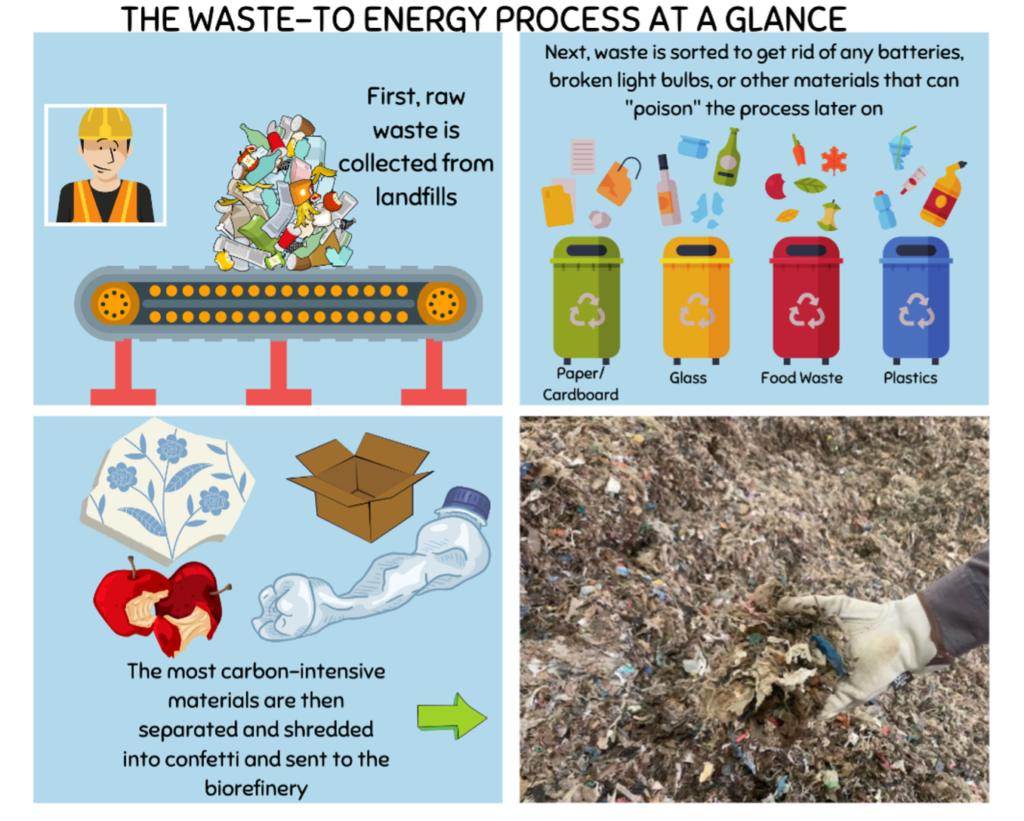

First, raw waste is collected from landfills, Valera explained. Next, the waste is sorted before it is sent to Fulcrum’s Feedstock Processing Facility. Any batteries, broken light bulbs, or other materials that can “poison” the process later must be carefully removed. The most carbon-intensive materials are then separated and shredded into a confetti-like material that is sent to the Sierra BioFuels Plant.

Next, the wet, confetti-like material goes in a machine that removes all the moisture and leaves it as a dry and fluffy material. The dry material then travels up a ramp into the gasification reactor. Here, high temperatures and little oxygen help molecules from the confetti instantly break down into a gas. The gas, called “syngas,” then goes through a series of pipes to get rid of any mercury, CO2, sulfur, or other contaminants that remain.

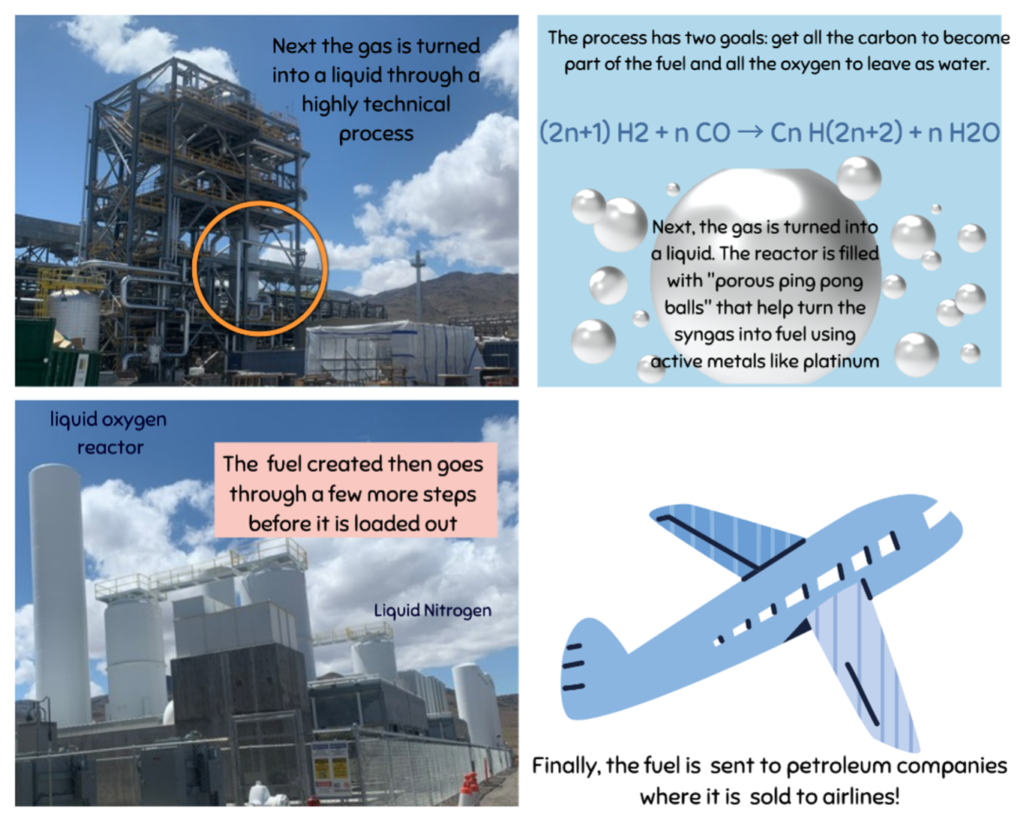

Finally, the gas is turned into a liquid at high temperatures through the highly technical Fischer-Tropsch process. The process has two goals: To get all of the carbon to become part of the fuel, and all of the oxygen to leave as water. The new fuel then goes through a few more steps before it is shipped off to petroleum companies and sold to airlines.

Reducing carbon aviation emissions

In 2021, the International Energy Agency reported that aviation accounted for over 2 percent of global CO2 emissions. Still, the demand for jet fuel continues to increase and is expected to double by 2050.

To learn more about the possibilities for biowaste-based jet fuel, renewable transportation, and whether we can expect turbulence or calm skies ahead, I spoke with UNR Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering Charles Coronella, Ph.D.

While Fulcrum is paving the way towards alternative and renewable aviation fuel, balance is no easy feat, Coronella explained. The aviation industry is one of the most important – and hardest to decarbonize. While common forms of renewable energy are useful for other modes of transportation, renewable aviation fuel requires innovation.

“You can’t use batteries in an airplane, they’re way too heavy,” Coronella said. “Solar is never gonna work for an airplane because the amount of solar that you could put on an airplane would be not enough to get a tiny little bicycle up. And so, it really requires us to come up with the process to produce aviation fuel that looks just like petroleum fuel.”

According to Fulcrum, their bioenergy plants reduce greenhouse gas emissions produced by traditional fossil fuels used for aviation by more than 80 percent.

Coronella is excited about the possibilities for what Fulcrum is doing. He feels that their goal to create a hydrocarbon fuel that acts in every way like a petroleum-based fuel is a promising step forward.

“They are leading the world,” Coronella said. “There’s nobody else doing what they’re doing. And I’m very excited that they’re doing it in our backyard. It’s very exciting that they’re doing it in Nevada.”

“We’re not going to run out of garbage anytime soon,” Coronella added. “It’s a nice renewable source that’s not taking resources from anything else.”

Valera, who has a master’s degree in sustainable energy and got his start working in the fossil fuel industry, also has high hopes not just for the future of the company, but for his children too.

“I have two young kids and making sure that I’m doing my due diligence and taking part in making sure they have a better future when it comes to climate change and pollution,” Valera said. “I’m passionate about it and I feel proud that at least from my sphere of influence, I put in effort and energy towards addressing some of the problems that future generations are gonna have to take on.”

The Sky is the Limit…

Still, it’s important not to put all your eggs in one basket. Or in this case, all your unsorted trash in one gasifier. While the idea of feeding converted trash to our airplanes sounds promising, it’s just one of the many options on the table for helping us reduce climate change.

Just a few hours before my visit, I had tossed a mix of rotting leftovers, fast food wrappers, and old receipts into my kitchen trash without a second thought. Now, when I look at the row of green trashcans that line the streets outside, I think about the possibilities. Up above, a plane drags across the blue sky. Its destination? A hopeful and renewable future.

Guadalupe Alvarez ’23 is a recent UNR graduate with an Anthropology major and Latinx Studies minor. She wrote this story for the News Studio: Science Reporting class at the Reynolds School of Journalism.