This story was shared with permission from KUNR Public Radio. For an audio version of the story, please visit the KUNR website.

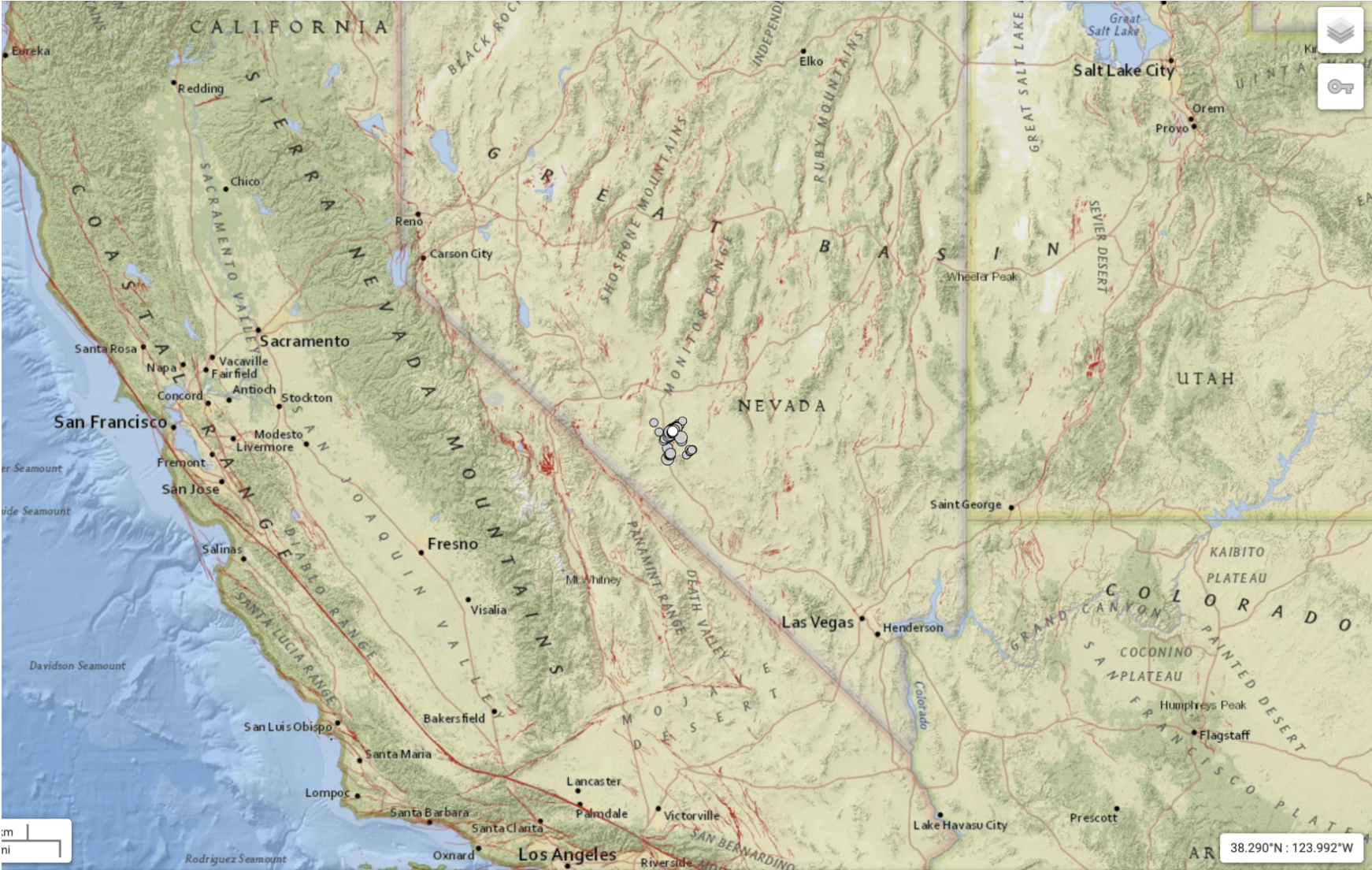

Earthquake sensors near the small town of Goldfield, Nevada lit up like a Christmas tree in early September when a swarm of over 300 quakes, often too small to be felt by the average person, shook the area.

Activity like this is normal across the Silver State, said Dr. Christie Rowe, director of the Nevada Seismological Lab on University of Nevada Reno’s campus.

The Nevada Seismological Lab, or NSL, has a network of over 300 earthquake sensors, known as seismometers across Nevada and parts of California. These sensors picked up the quakes near Goldfield and quickly triangulated their location and strength.

“Most of the earthquakes were under magnitude two. So people who were right there in Goldfield might have felt a couple of them, but our instruments felt hundreds,” Rowe said.

She said small swarms like this don’t necessarily mean a bigger quake is on the way, and Nevada is no stranger to a moving earth – over the past five years, the Silver State has had an average of 15,000 earthquakes a year. Like the recent swarm though, most of these are very small.

“We were getting 40 or 50 a day of magnitude one earthquakes down there,” Rowe said. “The amount of rock that’s breaking for a magnitude one earthquake might be like the size of a pea or a marble – really small. But if they’re happening over tens of kilometers of fault zone, it means something is shifting tectonically in the earth.”

Rowe said that earthquakes usually follow a size and frequency pattern, meaning that really large earthquakes are rare, medium earthquakes are medium rare, and small earthquakes are common. Nevada is prone to these small quakes though because of its unique tectonic makeup.

“Nevada is so cool because the state is spreading apart, and it’s doing it in a very unique way,” Rowe said. “So usually when a continent is breaking up, we get something like the Red Sea, or in the Gulf of California, or in Iceland, where it breaks in a central crack, and then the continent halves can move away from that crack.”

When a continent splits along a central crack, it concentrates all of the quakes along that one fault, but in Nevada things are a little different.

“What’s happening in Nevada and across Utah is that North America is slowly stretching apart. So we have many, many, many small cracks that are all working together to stretch North America, and that’s why Nevada is the fastest growing state – in kilometers, not population,” Rowe said.

Dr. Jim Faulds, associate director of Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology and UNR professor, also shed some light on the state’s very dynamic landscape.

“Tectonically speaking, we’re adding about two acres to the state every single year,” Faulds said. “Let’s say we go back 20 million years, the distance between Salt Lake City and Reno was half as much as it is today. So that’s how much the crust has stretched.”

These many faults in our landscape also accommodate motion from other plate tectonics beyond our borders. Western Nevada and Eastern California have a fault zone that accommodates 25 percent of motion between the Pacific and North American plates, Faulds said. The famous San Andreas fault in California accommodates 75 percent of this motion, but he said we make up for the rest.

These moving faults also are the reason for our unique basin and range landscape. As the crust stretches it breaks up, making faults, which move and bump into one another, lifting up mountains and dropping valleys one earthquake at a time, Faulds said .

The history of past earthquakes may be written in the landscape, but as for forecasting the next big one, Rowe said this is a bit harder.

“[We] Don’t know when the next one will come, but the big mountains and big valleys that we have here say that this has been happening already for 10s of millions of years and will continue to happen in the future,” Rowe said. “Could be tomorrow, could be in 1,000 years.”

Looking forward, Rowe said she does hope to expand research in the state and to integrate an earthquake early warning system in Nevada like the one in California. This would give a quick 10 to 40 second heads up to people if a large quake is on the way.

“In Reno we do have faults that run right through the city, which are potentially dangerous faults,” Rowe said. “We also know that there are big earthquakes that come from the Tahoe Basin and other faults that are a little bit farther away and the earthquake early warning system would work for that scenario.”

Both Faulds and Rowe said that regardless, it is always important to be prepared in case of a quake or natural disaster. They said it is important to make sure you have food, water, and a plan of where to go during a quake.

“There’s a temptation to run outside, but usually you don’t want to do that, you want to stay away from heavy objects. And building facing stone and brick is one of the things that falls,” Rowe said. “You want to have a ready plan for where you would go for safety in an earthquake. So I have this behemoth oak desk, and nothing will break through that desk. So that’s where I go.”

Kat Fulwider is the 2024 fall intern for KUNR and the Hitchcock Project for Visualizing Science.