Consider the Buckwheats

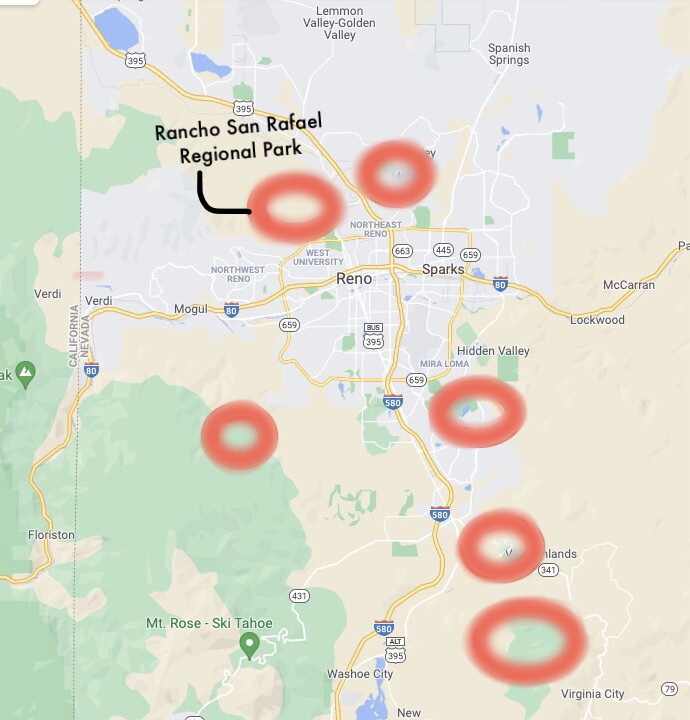

An extremely rare wildflower known only to grow in the Reno-Virginia City-area was recently documented on a parcel of land in Rancho San Rafael Regional Park. This also happens to be where a development agency wants to build 142 upscale townhomes. The proposed development, known as Rancho San Rafael Phase IV, lies adjacent to protected wildlife habitats and the Humboldt–Toiyabe National Forest. It’s also one of only fourteen scattered locations in Reno — as well as the entire world — where altered andesite buckwheat can grow.

Eriogonum robustum is one of the rarest members of Nevada’s extremely varied buckwheat family, and presents as a short perennial shrub with tiny red flowers and fleshy leaves. Because of Nevada’s hyper-arid and geologically diverse landscape, it is able to host hundreds of unique plant species that can survive nowhere else on Earth.

“This buckwheat is adapted to hydrothermally-altered andesite, which is a type of rock. And in the places where this hydrothermally-altered andesite occurs, the mineral content of the soil makes it very hard for other plants to grow. And, in that case, the buckwheat, over many thousands of years, adapted to grow in those highly-mineralized soils,” says Patrick Donnelly, the state director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

“So, now this species of buckwheat only grows in those soils — and nowhere else!”

Endangered? It’s Complicated.

Donnelly is known for his advocacy for the rare Tiehm’s buckwheat, which grows only in lithium-rich soil and is under threat from lithium mines. In recent months, he’s helped “Stop Rancho IV” petitioners survey the buckwheat population where the development is supposed to take place.

“The altered andesite buckwheat is imperiled in several ways,” says Donnelly, “Because it grows on what’s called the ‘wildland-urban interface’ — that’s the edge of the developed area. So it suffers from things like off-roading — like all those trucks and dirt bikes that pass right through the habitat. And then, of course, it’s under threat from all sorts of development. There’s a tremendous amount of development happening in its habitat, and the Rancho IV Project is an example of that.”

Though the shrub flourishes in some of the most harsh, barren conditions imaginable, it is still under significant threat from urban and residential development, highway and road construction and maintenance, off-road vehicle use, mineral exploration and extraction, and fire suppression activities. Much of its remaining habitat has been severely impacted, and permanent habitat losses totaling 51.4 acres — or about 6% of the historic population area — has been documented since the year 2000.

Hinge Points on NIMBY-ism

The altered andesite is listed as a BLM Sensitive Species, a US Forest Service Region 4 Sensitive Species, and ranked “Highly Vulnerable” by the Nevada Division of Natural Heritage. Despite these rankings, the plant has no formal protection on private lands — such as those under consideration for this development.

Opponents of the townhouse development in progress claim that it is in direct conflict with the Guiding Principles of the Reno Master Plan — particularly in regards to section 7.1D, which sets out to:

“(…) Promote the protection and conservation of significant wildlife habitats, slopes, stream and drainageway environments, prominent ridgelines, mature stands of trees, and other natural and scenic resources for purposes of wildlife survival, community education, research, recreation, and aesthetics.”

“Stop Rancho IV” petitioners say approval of the proposed development is in direct opposition with the goals of the Master Plan. Their change.org petition states that their intent is not to fight “development for the sake of fighting development.” But rather, to fight “development on this particular property.”

They write: “Bulldozing this unique corner of our city’s wildland is unconscionable.”

But halting the development might be only a short-term solution to the long-term problem of habitat degradation — if that’s even a possibility.

“The thing is, there are a lot of altered andesite buckwheats around,” says Donnelly. “Like, it’s definitely threatened — but if you look at the research, there are a lot of buckwheats [in Reno.] And the population on the Rancho IV development is very, very small.”

Donnelly says it’s not like the Tiehm’s buckwheat scenario — because in that case the entire global population of the Tiehm’s is within a footprint of that lithium mine. But the Rancho IV development only touches the tiniest little piece of the altered andesite buckwheats’ habitat.

“I’d be surprised if the altered andesite buckwheat is what stops this development,” says Donnelly.

Citizen Botanists Lead the Charge

But for Brooke Siem, a self-described “accidental activist” and founding member of “Stop Rancho IV,” retreat is not an option: “If you have the mentality that there’s just one population on the land — that there’s 14 more out there and the one fragment doesn’t really matter — well, that’s a slippery slope. It’s not just that I don’t want someone building in my backyard, it’s that I want to see this buckwheat through to the end. I think it’s a fascinating part of the world that so many people don’t know exists here.”

Siem says that she and other members of the ragtag coalition met by chance at a Reno City Planning Commission meeting on November 3rd: “‘Stop Rancho IV’ is just about as grassroots as you could get.”

Siem is learning Geographic Information Systems Mapping (GIS) and botanic canvassing on her own time in order to gather data for her cause. Using GAIA GPS software, she hikes out to established and potential habitat to painstakingly document scattered buckwheat populations. Siem says that her investment in the buckwheat comes from the fact that it strengthens her sense of place in the area she calls home:

“I grew up around here, and I love the desert. And then at some point, I found out about this plant, went down the rabbit trail, and absolutely fell in love with the little guy. [Rancho IV] is a piece of land that we feel is special and important — like, it’s not just some nondescript place. The fact that it houses a plant that’s endemic to only this part of the state — only this part of the world — is just incredible. The city council has made it clear that they want to keep Reno unique — from the ecology of the desert, to the businesses that operate around here.”

But Reno’s urban expansion into previously-vacant land is another symptom of the national housing crisis. According to new research from Realtor.com chief economist Danielle Hale, the U.S. is short 5.24 million homes.

“But it’s not like [the developers] are proposing low-income housing,” says Siem. “Many of those houses are going to have the best view in Reno.” According to the latest market reports, the median sales price of an existing condominium or townhome in Reno/Sparks is $294,000. Townhomes in Rancho III, the neighboring community, are currently listed at $439,000.

Though Desert Wind, the development agency, did not respond to a request for comment at this time, they will meet with petitioners in early January to discuss alterations to the project proposal.

Moving Forward

“The developer, to their credit, is making some changes,” says Siem. “And I appreciate that they are making those changes, whatever they may be. But whatever happens in this meeting, I want to get this plant listed. If there’s a case to be made — which I won’t know until I canvas all the populations — we could be looking at state or federal protection.”

Siem says that process will involve telling the story of the rare plant and then filing petitions with the government.

“From what I understand, the time it takes to get a species listed averages out to about eleven years. It’s a long endeavor, and I’m new to this. But I’m not jaded to the process — not yet.”

The Reno city council and planning commission will continue deliberation until Jan. 26, 2022, at which time a decision will be made. The parcel is located in Ward 4, under the jurisdiction of councilwoman Bonnie Weber.