With the right management, Nevada’s ranches and meadows are proving to be ideal candidates for carbon capture, a possible climate change solution.

Much of the Western United States is characterized by vast stretches of open land — the farms, ranches, mountains, and meadows that make up much of states like Nevada. At the University of Nevada, Reno, a growing amount of data is proving that these lands have the potential to actually capture carbon from the air and store it in the ground.

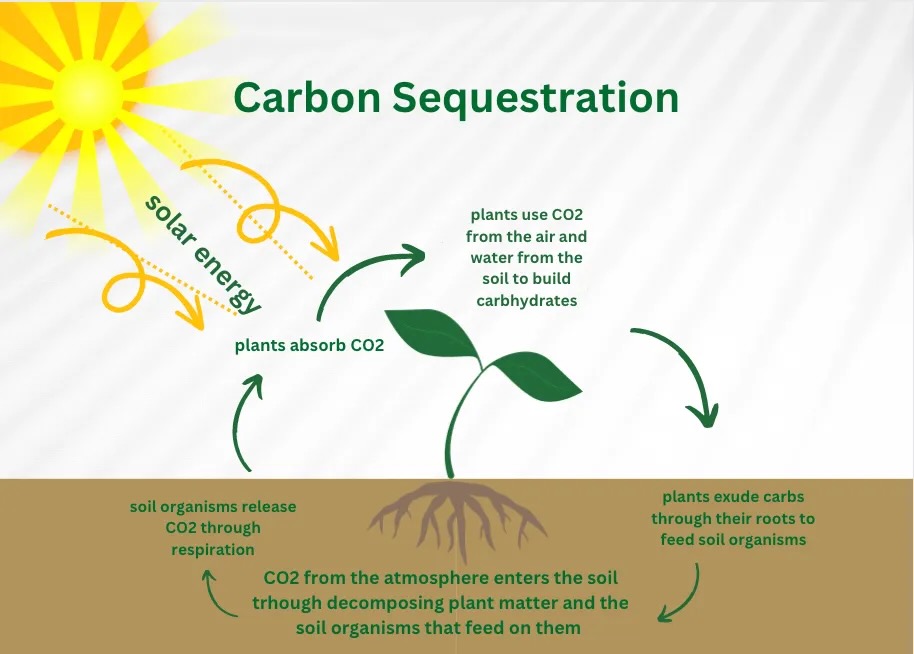

Carbon dioxide, one of the three major greenhouse gasses, is a heat-trapping gas that has increased by more than 50% in the atmosphere during the last 200 years. Carbon sequestration, or carbon capture, is the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. While it is a naturally occurring process, carbon capture can be enhanced with certain land management practices, a potential climate change solution that three local scientists are researching.

Carbon capture through better land management

For generations, Nevada’s rangelands have been managed to sustain livestock and produce millions of pounds of crops for the rest of the country. According to the Bureau of Land Management, Nevada has more public land authorized for grazing than any other state – about 43 million acres – but the state’s long tradition of ranching has proven hard on the surrounding environments, often leading to degradation and habitat loss, only intensified by the increasing frequency of droughts, floods, and wildfires.

Harsh land management practices coupled with climate change leave these rangelands in less-than-optimal health to be carbon farms.

Brian Morra, a postdoctoral researcher from the University of Nevada, Reno, centered his dissertation on the positive impact of carbon in soils and emphasized the need to manage Nevada’s land more sustainably in order to make them better for carbon capture. Morra found that lands with a history of high-intensity grazing have a lower ability to absorb carbon; but with the proper management tactics — timed grazing, crop rotation, or reduced soil disturbance, among others — could remove as much as 4–5 gigatons of CO2 per year from the atmosphere.

Morra works for the Agricultural Research Service in Reno, where he uses his research to assist land operators in managing their lands to yield higher productivity and less degradation.

“It takes a lot of thinking about the potential that piece of land has,” Morra says. “It comes down to finding ecosystems that once held a lot of carbon and then going in and finding ways to fix them.”

Carbon sequestration possibilities in meadow ecosystems

Less abundant but equally important components of Nevada’s landscape are meadows, another type of rangeland that also see their fair share of degradation from grazing and human use.

The Sierra Nevada mountain range boasts close to 18,000 meadows, so researcher Cody Reed and her team at UNR’s Soil Ecology Lab are surrounded with data that helps them to understand the impact of human disturbance in meadows, and what it means for carbon sequestration.

Depending on the health of a meadow, Reed says that they can either act as carbon sinks — meaning they take carbon from the atmosphere and store it — or they can be carbon sources — where old carbon in the soil is released into the atmosphere. “My research really started with asking the question of: are these meadows gaining or losing carbon, and at what rate?” Reed says.

By combining her data with machine-learning algorithms, scientists like Reed are able to produce complex models that can be used to predict carbon fluxes over time. “This will help us look at changes over time to see how much carbon has been gained or lost by a certain ecosystem, and how important they are to regional carbon budgets. Often these are under-studied ecosystems, but they often can sequester six times as much carbon per acre as an entire surrounding forest!”

Learning from Indigenous land management practices

While Nevada’s history of land management is long, the history of Indigenous land management tactics is longer and might offer critical insight into a more sustainable future.

UNR graduate student Casey White is also dedicating her research to studying rangeland health but with a focus on land ownership. White is looking into which management type — private, public, or tribal — proves more sustainable. Throughout her research, White looks at a region’s net primary productivity (NPP) in order to assess the health of the ecosystem; NPP refers to the amount of carbon that is fixed by photosynthesis in plants minus the amount of carbon that is used during respiration.

White says that lands under Indigenous control have a higher NPP, meaning these ecosystems are able to store more carbon than others.

“This is because tribally-controlled lands are being managed under traditional practices, which tend to value the land more and protect these resources in a way that’s more sustainable than modern agriculture,” White says.

White is advocating for further research of tribal practices; comparing these to modern public and private methods can provide valuable insights into how we can manage agricultural lands more sustainably. Rangeland Indigenous communities are among the most vulnerable to the impacts of a warming world, but have been most successful at adapting to changing climates by developing innovative farming techniques such as drought-resistant crops or water conservation practices.

“There’s a lot to learn,” says White.

Carbon sequestration: a win for all

Not only would the implementation of more sustainable land management practices help restore the health of an environment, but it would also aid in combating climate change by enhancing soil’s natural ability to capture carbon.

While integrating carbon capture as a substitute for traditional western ranching methods may be a long and pricey process, Morra says putting more money and research into carbon sequestration in soils is a win for all.

“We should be recognizing the ecosystem benefits that come with it,” Morra says. “Not only are we improving our atmosphere, but carbon in soils is a good thing for ranchers, for wildlife…elevated CO2 affects human health, people’s businesses. I think people need to set realistic expectations and ask: what is this worth?”

Hannah Truby is a graduate student in the Media Innovation program at the Reynolds School of Journalism. She wrote this story for Hitchcock Project’s News Studio: Science Reporting class.