IFrom working with NASA to freelancing for the Associated Press, Reynolds School of Journalism alumna Brooke Hess has been developing her skills in science communication and is now a filmmaker building her own production company.

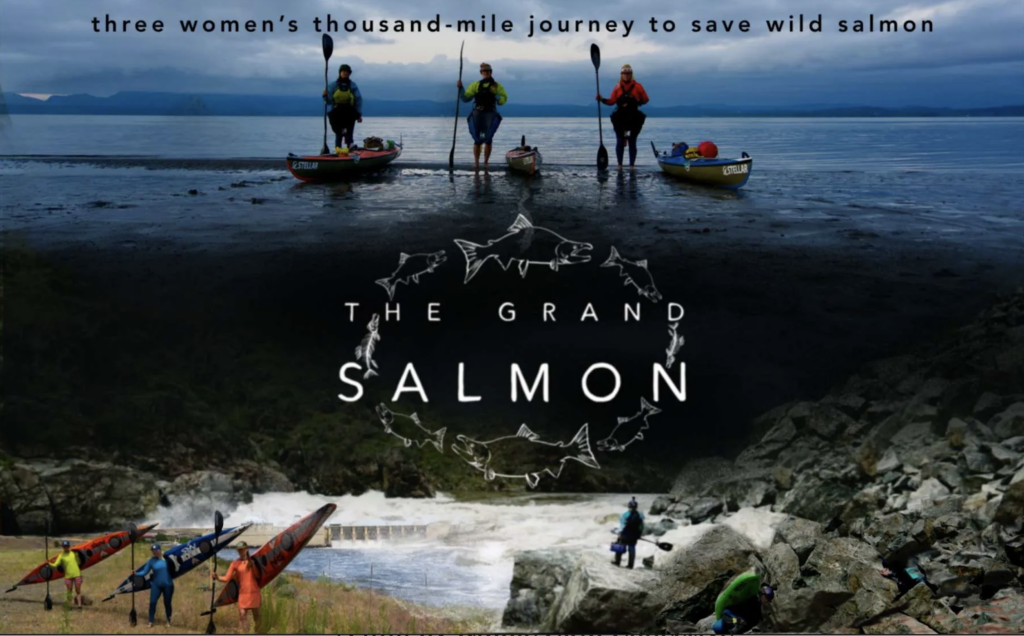

Hess, a former Hitchcock Project graduate assistant, visited the Reynolds School on Nov. 26 to showcase her documentary, The Grand Salmon—a powerful story that combines her passion for kayaking and conservation to spotlight the decline of salmon populations and the urgent need for preservation efforts.

In this conversation, Hess discusses the challenges of independent filmmaking, lessons learned in the field, and her vision for blending adventure, science, and storytelling to inspire action. She also shares valuable tips for aspiring science communicators.

HP: When did you get your master’s degree from the Reynolds School of Journalism? Can you tell us about your experience here?

Hess: I completed my master’s during the pandemic, from 2020 to 2021, and graduated in fall of 2021. My experience was incredible. I had the opportunity to work with Kathleen Masterson, a very experienced science journalist for NPR, who significantly improved my writing and served as an amazing mentor. I also did an internship at NASA’s space flight center, which was one of the coolest and most rewarding experiences of my life. I learned so much there. Overall, I think the professors here are excellent, and the program is very cost-effective for a journalism master’s degree, especially considering the value you get for such a low cost.

HP: Before joining the Reynolds School of Journalism, you were studying geoscience and kayaking professionally. How did you become interested in science communication? What made you realize you could write and work in this field?

Hess: When I was an undergrad studying geoscience, I thought I was going to become a geologist. I imagined it would be all about climbing volcanoes and doing really cool fieldwork. But when I actually did my thesis and research in my senior year, it turned out to be a lot of sitting by the river counting rocks for one day, then spending 20 days working with Excel spreadsheets. It wasn’t as glamorous as I had imagined, and I realized that being a scientist wasn’t as exciting as I had hoped. That’s when I started writing. I thought maybe writing would be more exciting because I could cover a range of topics—one day about Venus, the next about rivers. I decided to explore science communication as a way to combine my love for science and writing. I did an internship at NASA, which was the second coolest thing I’ve ever done (after The Grand Salmon documentary). That experience really solidified my passion for science communication. Now, I’m doing it through documentary filmmaking, where I get to tell scientific stories in a way that engages people.

HP: What was the topic of your master’s project, and how is that related to what you do now?

Hess: Before I became a professional guide, I earned a bachelor’s degree in geoscience—I was just a scientist. Then I decided I wanted to combine my science background with writing, so I applied to this program and a few others. The Hitchcock Project here really stood out because it’s so strong in science journalism. When I was applying, I was talking to my good friend Libby—who’s in the film and a co-producer with me. At the time, we were both leaving decade-long careers in the whitewater and outdoor industry to go to grad school, which felt really daunting. We wanted to come up with a project that would combine our water expertise, bilingual skills, and passion for conservation.

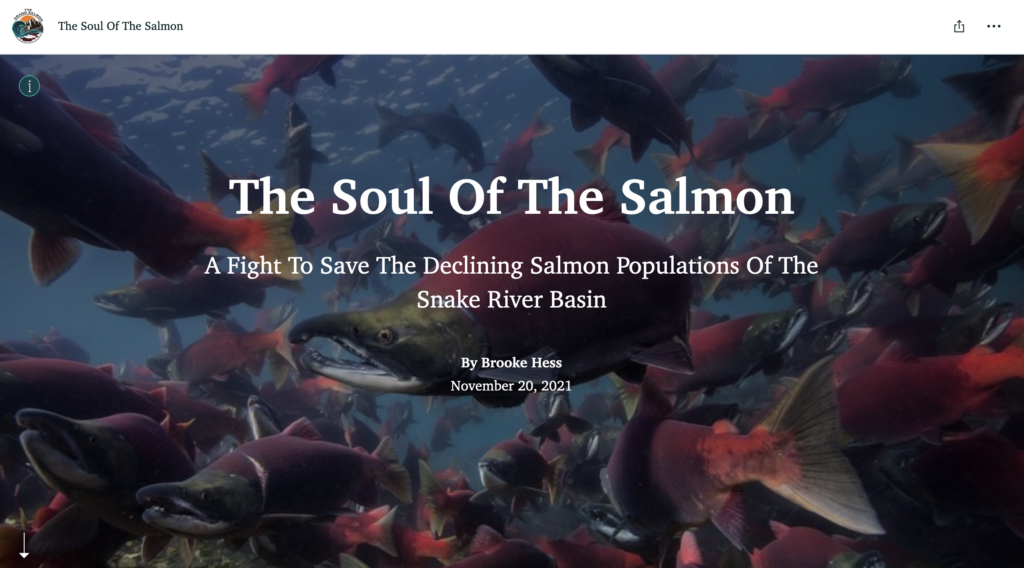

What we came up with was a project focused on the declining salmon populations in the Snake River Basin. Those rivers are places we paddle in all the time, so the issue felt very personal. I decided to use my master’s project to dive deep into this topic. Kathleen Masterson, who used to run the Hitchcock Project, was an incredible mentor. She helped me shape the project and learn everything I could about the topic. The result was a big multimedia project for my master’s: a 7,000-word article broken into sections with videos, audio, photos, and interactive elements. I wanted it to be engaging—something with lots of things to click on—because I know scientific topics can intimidate people who don’t have a science background. The goal was to make it interactive and accessible, so readers could stay engaged with the story.

HP: And then, how did that become The Grand Salmon project?

Hess: Libby and I graduated in December, and we had been planning our expedition to follow the natural migration of these salmon populations that are at risk of going extinct. The following spring, we completed the expedition, trying to better understand why these fish are disappearing. That expedition turned into a feature documentary film. The film has taken off—it’s screening a lot, and people are really enjoying it. It’s been a successful project in the sense that it resonates with audiences and touring on the film festival circuit. By “successful,” I don’t mean we’re making money—because we’re not. We haven’t yet figured out how to pay ourselves. But this project has really turned into my career. What started as a master’s project and a film is now a 10-year-long commitment to telling this story, understanding these salmon, and advocating for the rivers they depend on.

HP: Where did the funding come from for your documentary?

Hess: Funding independent films is one of the biggest challenges I’ve faced. A lot of our funding came from my kayaking sponsors that I worked with throughout my career, so it’s actually a branded documentary film, which I think is pretty rare. Northwest River Supply and Jackson Kayak gave us significant support. We also received some funding from nonprofits, like American Rivers and the Save Wild Salmon Coalition. Additionally, we ran a Givebutter campaign, which is similar to Kickstarter or GoFundMe but designed for nonprofits. We partnered with Idaho Rivers United, a nonprofit, as our fiscal sponsor. By doing that, we were able to funnel donations through them, making contributions tax-deductible. Donations technically went to their 501(c)(3), so everything was completely legitimate tax-wise, and the partnership really helped us fundraise. Beyond that, we secured private donors and sponsorships, but a big part of the reality is that we didn’t pay ourselves. I still haven’t figured out how independent filmmakers make a living doing this. I think the key is often to work on commercial projects to fund your independent, passion-driven films.

HP: Aside from the financial aspect, what were the challenges of working on this project?

Hess: We made some big mistakes at the start because we’d never done this before. One of the major challenges was around the production process. A lot of the film was shot on GoPros, iPhones, and some pretty cheap mirrorless cameras. Later on, we brought in professional filmmakers to capture higher-quality footage during the expedition. However, we made a crucial mistake: we didn’t have them sign contracts. Because of that, we ended up losing a lot of our footage. There was one filmmaker whose work we weren’t happy with, and we decided not to have her continue. Unfortunately, she never returned the footage she shot or the camera gear we had purchased specifically for the project. This was a hard lesson to learn: when you’re essentially starting a business or a major project like this, contracts should always come first. It’s not something you typically learn in journalism school, but it’s so important to protect yourself and your work.

HP: Looking at the project now, what are the things you would have done to make it better?

Hess: There are definitely parts of the film I don’t even like watching now because I’ve seen it so many times, and I’m so critical of it. I look at certain scenes and think, “We could have done that better.” I wish we had better whitewater shots and river shots—those are such a big part of the story. I also wish we had included more tribal interviews to deepen that perspective. One thing I do think we did really well was the science communication. We have strong graphic design and really effective graphics that explain the science behind the salmon population’s decline. But overall, better cinematography would have made a big difference. I suspect that’s part of the reason we didn’t get into certain film festivals—some of our cinematography just isn’t as polished as it could be.

HP: Can you tell us about your NASA internship? How did you find out about this opportunity, and what would you recommend to students who might not even think it’s a possibility?

Hess: Honestly, I probably just Googled something like, “Does NASA have a science writing internship?” and found it that way. I applied without ever thinking I would get in. Then I got an email saying they wanted to interview me, and during the interview, they told me I had already been selected! Out of over 3,000 applicants for the science writing internship, they chose just ten of us. I felt so lucky to be part of it.

The experience was incredible, even though it was during the pandemic, so the internship was remote. These days, they pay interns to live in D.C. and work at the Space Flight Center, which would be an even cooler experience. Still, they did a great job running it remotely. There were events, lots of learning opportunities, and we even had a little internship cohort that bonded so well we still have a group chat to this day.

For students who don’t think it’s possible: just apply. You never know what might happen, and opportunities like this can be life-changing.

HP: Can you talk a little bit about your freelance career and how it all came to be? It sounds like you’re juggling a lot with your production company and other projects. How do you manage everything, and what is your life like as a freelancer?

Hess: Right now, I’m trying to turn my production company into a full-time job for myself. It’s a challenge, especially since I’m not paying myself yet. To make ends meet, I do freelancing, doing things like ghostwriting or covering events for the Associated Press (AP), while focusing on my production company on the side. It’s not always glamorous, but it’s all part of the process.

I actually got my job with the AP through an event at RSJ when I was in grad school. Marcio Sanchez, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer for the AP, came to speak to our journalism class. I went to his talk and had the chance to meet him during a coffee hour. He and I started chatting about my background, and I mentioned my experience in hiking and photography. We had already been following each other on social media for a while. Then, last year, he reached out to me on Instagram because he needed a new reporter in the Truckee-Tahoe area. He asked if I’d be interested in working with AP as a photographer, and I told him, “I’m not really a photographer, I’m more of a writer.” He said, “You know how to use a camera, right?” And I said, “Yes, I took Dave Calvert’s class.” And that’s how I ended up freelancing for the AP. I cover national news events like storms, wildfires, and major events in the Tahoe area. Whenever something big happens, he calls me, and I go out to shoot photos and videos. The cool thing is you don’t need the best camera gear to start freelancing with AP. I’ve been shooting with a $600 Sony camera, and when I mentioned this to Marcio, he said, “That’s enough—you’ll upgrade your gear later.”

HP: How do you think the skills you learned during the master’s program have helped you in everything you’re doing now?

Hess: The most helpful course I took was Dave Calvert’s photojournalism class, especially in terms of learning practical, applicable skills. He taught us how to use a camera and gave really valuable feedback on our photos. One of the most useful parts of the class, though, was when he focused on marketing ourselves as freelancers. For example, we created our own websites, which he reviewed and gave feedback on, and he required us to get photos published professionally during the course. That process really pushed us to build a portfolio. As a journalist, having a strong website is essential, and the lessons on the business side of freelancing—like how to market yourself and sustain a career—were incredibly valuable. Those skills have been so helpful for me as I’ve moved forward in my career.

HP: What tips or advice would you give to students interested in science communication, especially in multimedia?

Hess: You do not need the best camera or the most expensive gear to get started. You can have a $1,000 setup and still produce professional-quality work as a photographer or filmmaker. The key is to just start creating. Don’t wait until you have the “perfect” equipment—you can always upgrade later. Focus on building your skills, telling great stories, and improving your craft with what you have. and engage with them about it. And definitely don’t be afraid to feel stupid and ask lots of questions.”

Vanesa de la Cruz Pavas, M.A., is a reporter and science communication specialist for the Hitchcock Project. She is a graduate of the Reynolds School of Journalism’s class of 2023.