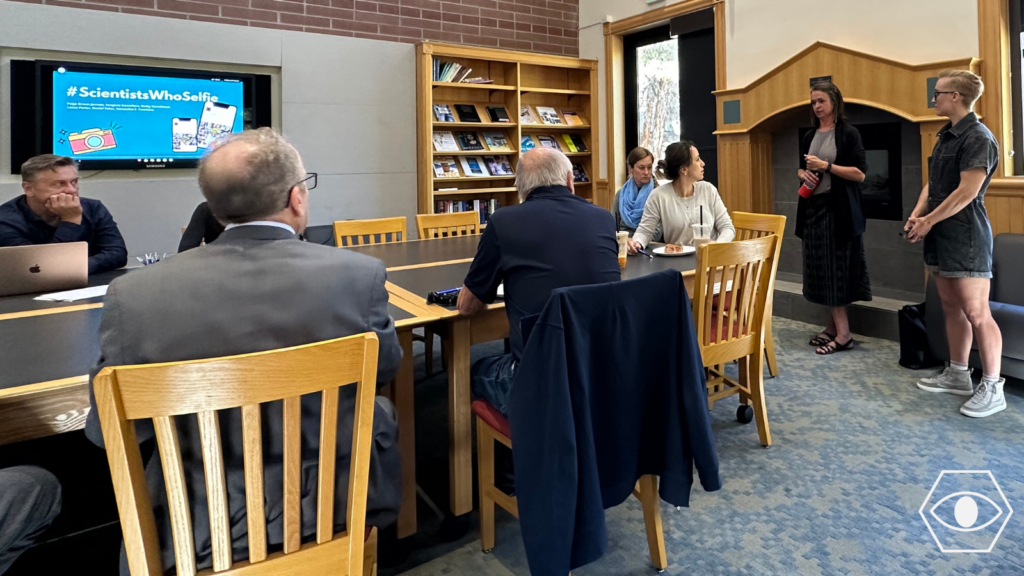

Science communicator Paige Jarreau, Ph.D., visited the Reynolds School of Journalism in early October to speak with students and faculty about her work, and how she connects scientists and writers in order to improve the world of science communication. While she now pursues science communication full-time, Jarreau’s career started out a little differently.

While she was pursuing a degree in biochemical engineering, Jarreau realized she might enjoy writing about the field rather than practicing it. She then moved across the country, enrolled in a new program, and received a Ph.D. in Mass Communication. Jarreau has since held a variety of science communication roles; in addition to offering workshops and contracted consulting, Jarreau now works for the NIH Center for Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias (CARD).

Hitchcock Project reporter Hannah Truby spoke with Jarreau to learn more about the challenges of science communication, as well as the opportunities for both scientists and communicators to tell more engaging stories about science.

Truby: When did you decide to make the pivot from the world of science to the world of communications? Was there a moment you can remember?

Jarreau: During my Ph.D. program in St. Louis, I was writing a lot of the SOPs [Standard Operating Procedures] because a lot of the students were foreign in that lab. As I was writing, I started to think: ‘Maybe I like this better!’ At that same time, I started what began as a newsletter. I wanted to cover the science behind movies. It turned into a blog that I pitched to Nature Network, and they liked it. I was blogging every day after that and started meeting other science communicators online through that medium. It opened my eyes to what could be a new career path.

Truby: What comes with having a foot in these two seemingly separate worlds?

Jarreau: I mean, so many benefits. I had no communication experience when I started the program, but coming from my background in research, I think I was able to jump into science communication research easily. And even just having started a website gave me some experience in strategic communications. Now, I’m able to offer different perspectives on both worlds.

Truby: What are some of the biggest challenges in science communication today? What roadblocks do scientists face when it comes to relaying information to the public?

Jarreau: This is a hard one. I think that as scientists, some of our first reactions are from a place of frustration. You have an agenda, information you want to convey, and you see people getting it wrong, or people not understanding something properly. And I think that the standpoint of frustration can be kind of dangerous when trying to push information out there. What comes to mind is the pandemic.

Science communication research is all about taking a step back, trying to get to know your audience, and start asking questions like ‘What is most important here?’, ‘How do we approach that?’ Science communication offers strategies for that.

Truby: I know you offer various science communication workshops – are these designed with scientists in mind or journalists? Or both?

Jarreau: Both! But I might say different things to different parties. When it comes to scientists, the workshops are meant to prepare them to tell their stories, educating them on how to form relationships with your audiences along the way; how to keep in touch with people, and document your science in such a way that it’s easy when it comes time to share your information – ahead of a crisis, for example, rather than having the questions of how to connect with audiences be an afterthought.

Truby: So then, in that case, what are some ways scientists can do to improve their communication to the public?

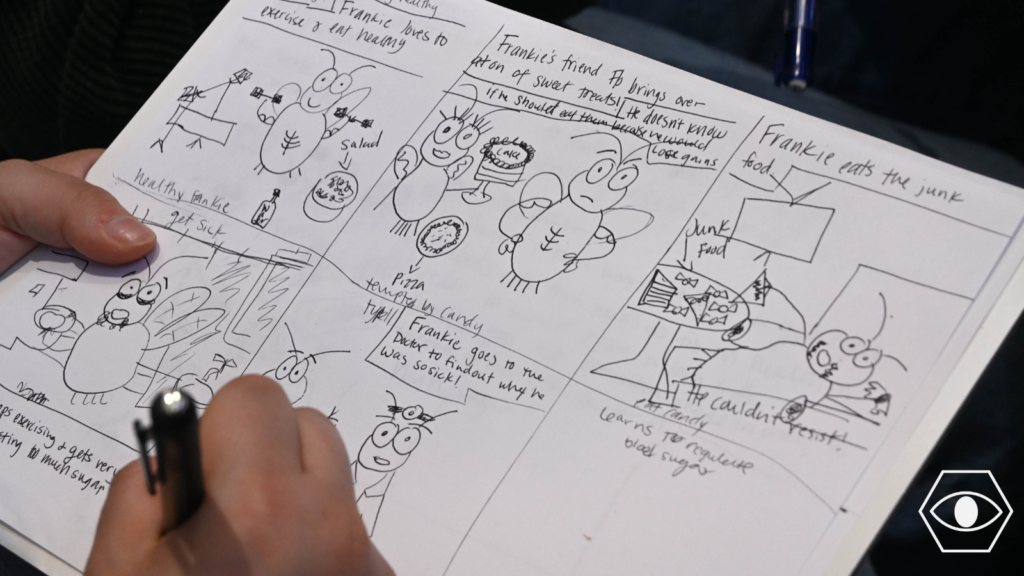

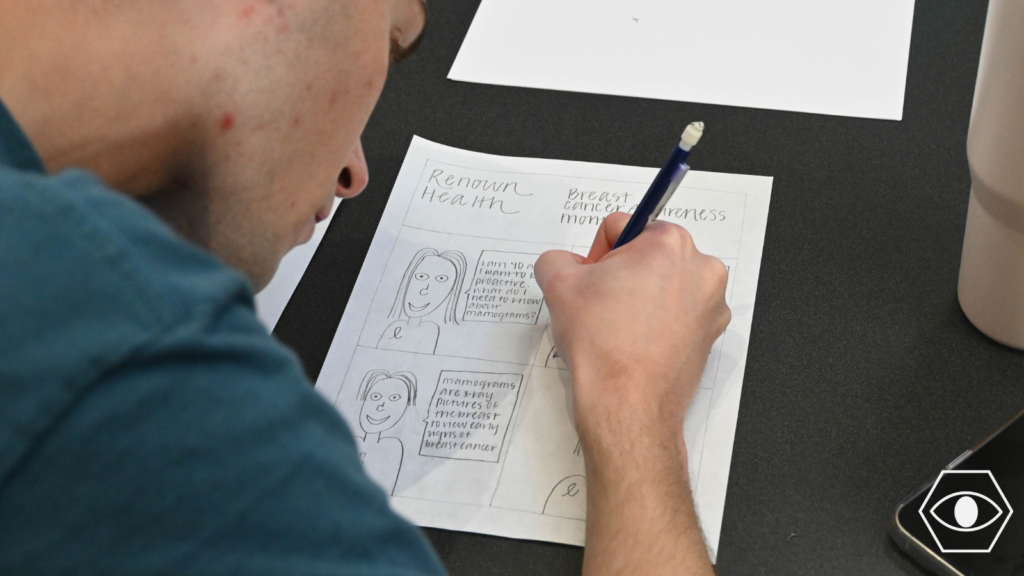

Jarreau: First, I get them to pinpoint what their goal is, if they have one. If it’s just about relaying information, I encourage them to think about creative ways to go about it. As humans, we’re humans, we’re wired for story. People remember information better if they consume it in some story form. We should tell stories, utilize emotion, and share personal experiences – people will relate to those more. And then I give them practical tips for how they can go about it.

Truby: Do they collaborate with someone? And do you put them in touch with that person?

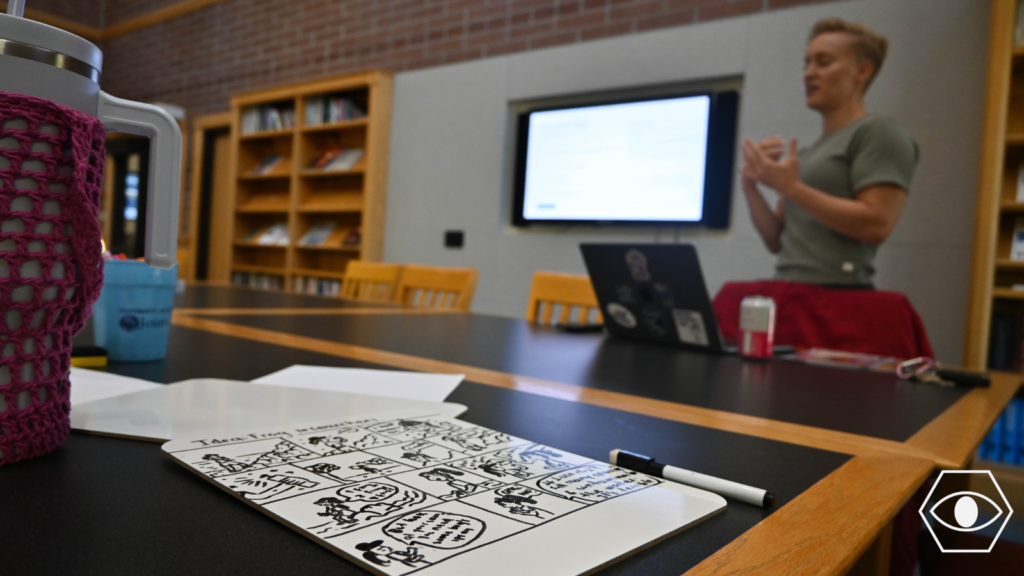

Jarreau: When I’m talking to scientists, yes, they can do this themselves if they want, through a blog or whatever platform. But I encourage them to go further by collaborating with professional storytellers, designers, artists, and people who are educated in how to elicit emotions and tell stories.

For science writers, it depends. Sometimes if they’re working directly with scientists, I might educate them on how to talk to scientists, the right questions to ask, what to look for.

What are some of the main points you want scientists/journalists to take away from your workshops?

For scientists, one of the first things I really want to focus on is reminding them not to not to assume the audience has some dearth of knowledge, and you’re going to ‘fix’ them with this information – whether it’s to improve their attitudes towards science, get them to vote a certain way, or get them to get their vaccine. That deficit model approach is just about delivering the facts and getting information across. But often, scientists don’t fully understand how complicated people’s opinions of science are.

That’s interesting. Why do you think this is? What are some things that can impact a person’s attitude toward science?

According to evidence we have in science communication research, we can’t just deliver facts to people; there’s a lot of other things that guide their attitudes towards science. When it comes to communicating to people who have been mistreated historically by science, for example, there’s a lot more nuance there, and a lack of trust in science authorities.

You have to build trust and relationships with the public before even thinking about communicating with people in different languages or from different backgrounds. They have to use good communication practices up front, like establishing trust with their audiences. That’s where it gets tricky, but it’s also the fun part.

I would imagine the hardest part for scientists would be trying to, for lack of a better phrase, “dumb down” their information. But it can be hard to get the public to understand the more complex stuff.

It’s a bit of an old school viewpoint, but this idea of not wanting to dumb down the science is still big. From a strategic science communication standpoint, you have to understand that your goal in trying to get people to understand starts with why they should care.

It’s not so much about dumbing down the science, because the goal is something different. So you can tell your story and you can keep it simple, because the goal wasn’t to have them have a definition textbook of this thing. That leads to exploring new ways of communicating, and asking things like, ‘What stories will I tell that will make people care?’

What do you think is in store for the future of science communication?

I can’t predict the future of course, but my personal opinion is that immersive media experiences will increase; things like virtual reality and AI video will continue to change the way people consume information.

I also think there’s a greater awareness now post COVID about how important it is to have people that know what they’re doing in science communication and to be practicing good communication before a crisis happens. I think a lot more organizations are realizing that they need to be doing this along the way, which is hopeful.

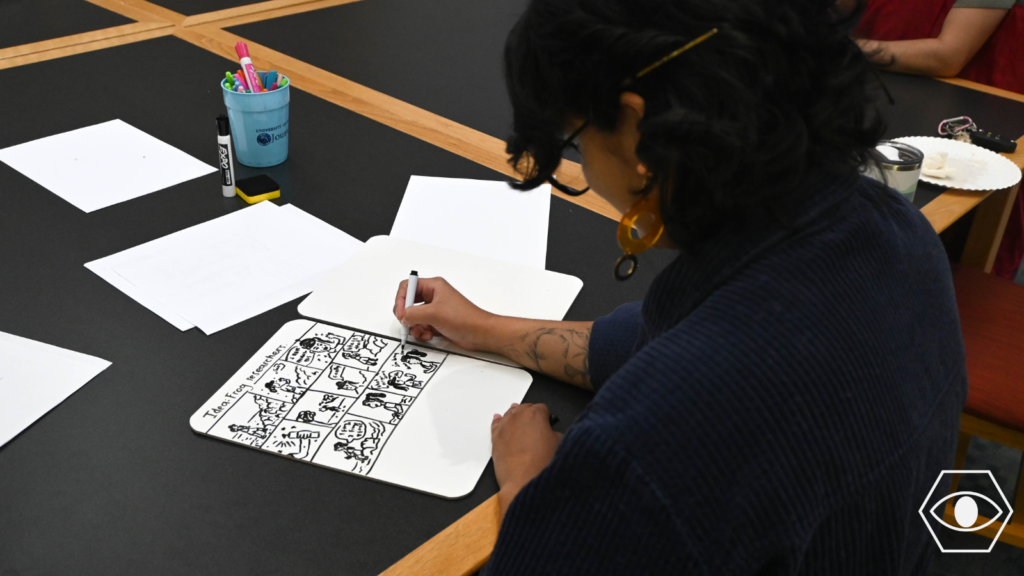

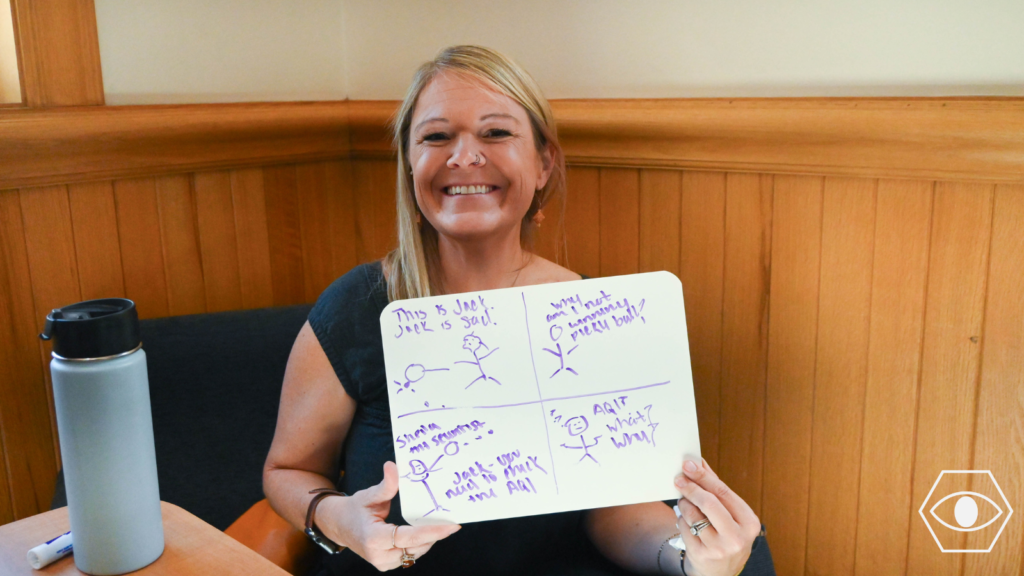

Photos: Paige Jarreau’s “Art of Science Communication” Workshop. October 5, 2023.

Hannah Truby is a graduate student in the Media Innovation MA program at the Reynolds School of Journalism, and a reporter for the Hitchcock Project.